Electioneering: Now is the time to not see it

Due to a quirk in campaign finance law, as election day draws closer, political nonprofits have an incentive to be explicit in their attack ads if they want to keep the identities of their donors a secret.

Corporations organized under sections 501(c)4 or 501(c)6 of the tax code aren’t required to disclose their donors to the public, even though many spend money on political ads and report that spending to the Federal Election Commission. But a 2012 federal court case over language in the McCain-Feingold law resulted in a ruling that would force nonprofits to disclose donors if they mention federal candidates in broadcast ads within 30 days of a primary or, 60 days of the general election — a window we have just entered in the 2014 campaign.

But if you’re expecting to discover the names of donors behind dark money groups that run attack ads, don’t hold your breath. If past cycles are any indication, issue advocacy will all but disappear when the reporting period begins. That’s because of a distinction election law makes between an issue ad, which might say, for example, “Tell Sen. Smith to support lower taxes,” and express advocacy advertisements, which might say, “Vote that bum Sen. Smith out of office.”

Functionally, issue ads — also known as electioneering communications — may be indistinguishable from express advocacy to a layperson. Without using the word vote, the Swift Boat Vets ran ads that questioned the military record of then Democratic presidential nominee John Kerry, leaving little doubt as to how the group wanted viewers to vote. Issue ads often showing a candidate’s likeness and call viewers to action — including this Colorado spot: “call Mike Coffman and asks him if he stands with Big Oil or with Colorado veterans”). If VoteVets runs its ad on Rep. Mike Coffman, R-Colo., more than 30 days before a primary or 60 days before the general election, it doesn’t have to report the spending to the FEC. Within those 30 and 60 day windows, VoteVets must file reports of electioneering communications to the commission.

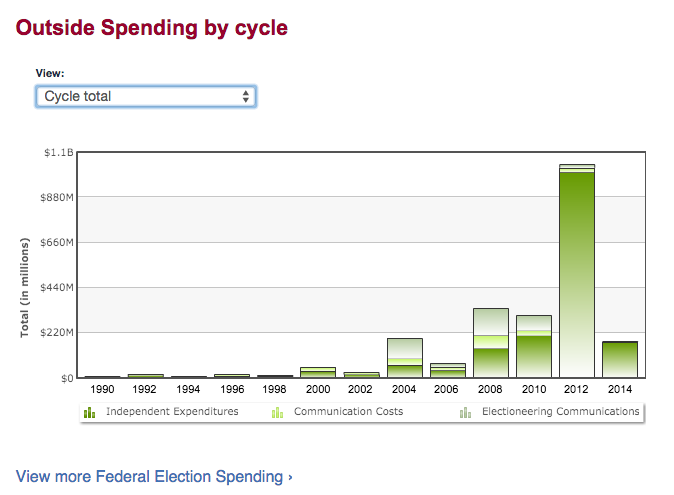

Source: Center for Responsive Politics

Source: Center for Responsive Politics

The McCain-Feingold law, enacted in 2002, required nonprofits running electioneering ads to disclose their donors. The FEC interpreted this to mean donors who explicitly paid for the ad; Rep. Chris Van Hollen, D-Md., sued the commission over its interpretation; a federal judge agreed that that statute requires disclosure of all donors, not just those who contribute for a specific ad.

As electioneering spending data compiled by the Center for Responsive Politics shows, the amount spent on electioneering communications, which had been shrinking, all but disappeared in the 2012 cycle. But dark money won’t sit on the sidelines: after the 2010 Supreme Court ruling in the Citizens United case, dark money groups can pay for express advocacy (also known as independent expenditures) to avoid any requirement to disclose their donors because election law doesn’t require it.

And there are a lot of groups ready to pour dark money into express advocacy. Since the beginning of the election cycle a host of new, under-the-radar outside spenders have entered the campaign arena. Take the two below for example.

American Encore is a Koch-affiliated nonprofit formerly known as the Center to Protect Patient Rights. In past cycles, CPPR played the role of banker to other groups associated with the Koch brothers, receiving and disbursing cash to other electorally active organizations in that network. Since then, however, American Encore has veered from that path, running ads in races in Arizona, Minnesota and Nevada contracts show.

Ads on its YouTube page show the group has waded into state politics in Arizona, pulling for Republican Doug Ducey in that state’s gubernatorial election. In Minnesota, Encore is going after Democratic Sen. Al Franken — spending some $250,000 on an ad campaign to that effect, according to the Wall Street Journal. The campaign blasts the incumbent for supporting a proposed IRS rulemaking that would reign in political spending by nonprofit groups like American Encore.

The group ran a similar ad against Sen. Harry Reid, D-Nev.

The group has not yet reported any independent expenditures to the Federal Election Commission.

Another new face on the scene, the Environmental Defense Action Fund, has gobbled up airtime in television markets in at least six different states according to a review of TV ad contracts.

The Action Fund, organized as a 501(c)4 social welfare organization, is the new advocacy arm of the Environmental Defense Fund and boasts some serious dollars to its name.

Though in past cycles EDF has stood solidly behind liberal candidates, it broke with tradition this year in backing Republican Rep. Chris Gibson over millionaire Democratic challenger Sean Eldridge in New York’s 19th District, perhaps signaling a new willingness to ‘play ball’ with certain Republicans in the GOP-controlled chamber.

The group has already spent over $750,000 in negative ads against Republican Senate candidates in Colorado and Iowa, reports of independent expenditures to the FEC show, but the full total of its political spending isn’t clear.

Sunlight reporting was able to find a record of the EDAF’s New York spending before the ad hit the air by searching political ad files published to the FCC, but this data is unstandardized and often incomplete.

It’s unlikely that the full list of donors behind either of these groups will be brought to light any time soon.