Private memo reveals winding tale involving John McCain, the NRA and … condors

Spotting #California Condors at Vermilion Cliffs Nat'l Monument – Save the Condor, use unleaded ammunition! #Arizona pic.twitter.com/kinGKljo2j

— John McCain (@SenJohnMcCain) August 25, 2014

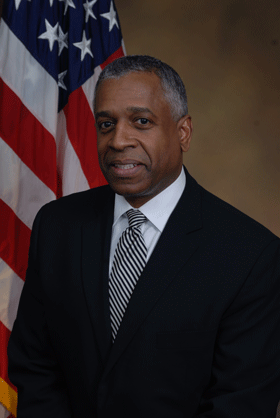

Jones didn’t come to the phone, in spite of — or maybe because of — the fact that his nomination of the besieged agency was coming for a vote before the Senate the following day. McCain was a key player: He had helped broker a deal with Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, D-Nev., to end the filibusters that had stymied so many Obama administration nominations.

McCain spoke to Jones’ chief of staff. The senator’s request? That Jones come to an Arizona summit the following month on the state’s program to protect the endangered bird.

Why would McCain take the step of calling Jones at such a sensitive time to talk about, of all things, birds? Why did he think that Jones’ participation in this particular meeting was so crucial?

Sunlight found the record of the telephone call placed by McCain to the ATF, which has not been public before, among thousands of pages of documents we received from the ATF via a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request, which we analyzed with the help of Overview, an open source tool that allows journalists to find themes in large sets of documents.

A McCain staffer says the senator’s motivation came from a long-held desire to save the birds and to promote Arizona’s program that encourages hunters to give up lead ammunition, which has been tied to condor deaths. The state’s voluntary program is in lieu of a legal ban on lead ammunition.

But the public record shows that McCain’s efforts to intercede mesh with the interests of the National Rifle Association (NRA), which endorsed the senator during the 2008 presidential campaign and spent $7 million opposing his rival, President Barack Obama, and again endorsed him in his 2010 Senate race. The NRA and the ATF did not return requests for interviews for this story.

That summer was a fraught time in the annals of battles over lead ammunition. The California legislature was debating a bill that would ban outright the use of these types of bullets statewide. The ATF, meanwhile, was reconsidering restrictions on certain brass bullets deemed “armor piercing” that are used by hunters as alternatives to lead ammunition. And the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was facing efforts by the Center for Biological Diversity and other conservation groups to ban lead ammunition under federal toxics laws.

McCain felt that these parallel efforts were pressuring Arizona’s condor preservation program at all ends. The ATF was considering squeezing out copper bullets, which local conservation groups, such as the Peregrine Fund, were worried would hurt the state’s voluntary program to preserve the birds. The NRA fiercely opposed any new restrictions on copper bullets and the proposed bans on lead bullets in California and the federal level. The senator felt, according to his aide, “There is no one thinking about the condor.”

With a wingspans stretching nearly 10 feet, the California condor is the largest flying bird on the continent of North America. They once ranged from Canada to Mexico and were plentiful in the Grand Canyon, but, by the time Europeans came to America, most of the big birds lived in California. With hunting, development and other encroachments on their territory, the numbers of condors dwindled fast; in 1967, the federal government listed the condor as an endangered species. Nevertheless, their numbers continued to dwindle, and by 1979, there were only about 30 birds remaining in the wild.

In the 1980s, work began to breed condors in captivity, with the goal of reviving the population. And in the following decade, in both California and Arizona, conservationists began to introduce these birds back into the wild. As of June 2014, 225 condors fly the skies of California and the Vermillion Cliffs in Arizona, while 214 live in captivity.

But wild condors have continued to die — and the evidence points toward lead poisoning. As scavengers, condors frequently feast on “gut piles” left behind by hunters who have shot deer with lead bullets. When they eat, they also ingest lead;indeed more than half of the condors tested are positive for lead exposure, many at such dangerous levels that they must be treated by chelation therapy. “[T]he prevalence of lead poisoning in California condors is of epidemic proportion and … the principle source of lead poisoning is lead-based ammunition,” concluded a 2012 paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that utilized isotopic analysis to link the lead found in condors with the lead in spent ammunition.

The NRA, however, has never accepted that lead ammunition is a major cause of condor poisoning and strongly opposes any attempts to ban it. In June 2007, when the California legislature was considering a bill to ban lead ammunition in areas within the range of condors, the gun rights group commissioned a study concluding that “lead ammunition as a major source of elevated lead in condors is not supported by the scientific data presented.” They urged members to oppose the legislation and then, when it was approved by both the Assembly and the Senate, to contact then-Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, R, and demand he veto it. In that case, the gun rights group lost: Schwarzenegger signed the new law in October 2007.

In 2008, as the presidential race heated up, McCain actively sought the support of the NRA. It was a tricky relationship, because McCain’s record, while generally pro-gun rights, included some positions opposed by the NRA — most notably, following the Columbine school shooting, he came out in support of background checks for firearms bought at gun shows. The NRA also fiercely opposes campaign finance reform, which McCain championed in the 2002 Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act. In 2004, the NRA gave him just a 50% “lifetime rating,” according to Project Vote Smart, although in the 1990s he’d earned a “100%” rating.

But in the presidential contest with Barack Obama, McCain was the clear choice for the NRA, and the official endorsement came in October. At that point, the NRA had already spent more than $2.3 million on independent expenditures opposing Obama, according to the Washington Times. By the time the election ran its course, the NRA would drop nearly $7 million against Obama and more than $289,000 in favor of McCain, according to OpenSecrets.org.

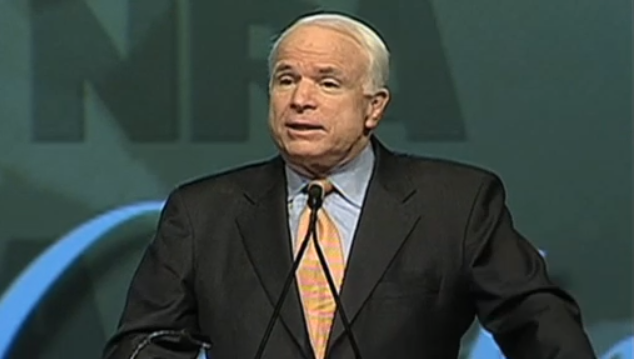

In 2009, McCain addressed the NRA’s national convention. He thanked the group for its endorsement, adding, “It also meant a great deal to me personally, and I thank you, and I’m in your debt. I promise you I intend to honor that debt by remaining worthy of the support you gave me and standing with the members of the National Rifle Association as you defend our liberties and resist unnecessary encroachments on them by government.”

The NRA endorsed the senator for his 2010 Senate campaign; the support was particularly noteworthy since McCain faced a challenge from the right in the primary, by Rep. J.D. Hayworth. In its statement, the NRA specifically highlights McCain’s “commitment to preserving our hunting heritage,” and his consistent votes against “ammunition bans.” The NRA spent $7,900 in support of McCain, who in the general election far outraised his Democratic rival, just $1.3 million compared to McCain’s $5.8 million that cycle, according to Influence Explorer.

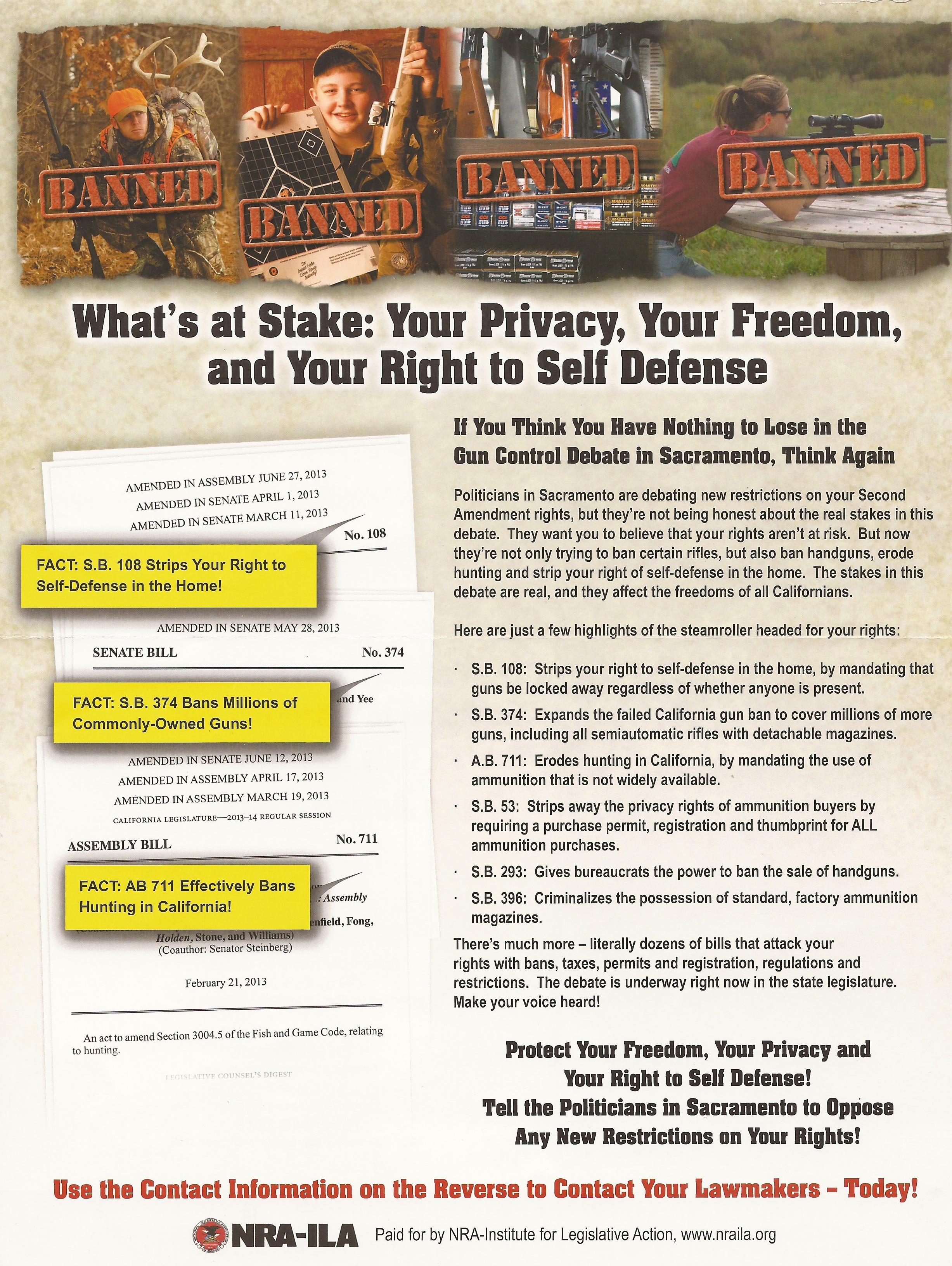

In the summer of 2013, the issue of lead ammunition was heating up again. In Sacramento, the state legislature was considering a bill, Assembly Bill 711, which would ban lead ammunition in the state altogether.

Meanwhile, the NRA was also actively fighting against a revived petition by the Center for Biological Diversity and other environmental groups asking the EPA to ban lead ammunition as a violation of toxics laws. The EPA had denied the petition, environmental groups sued and a district court dismissed the suit. In another lawsuit, the Center had argued that the U.S. Forest Service should ban lead ammunition in Arizona’s Kaibab National Forest. (Since then, the environmental groups have filed an appeal in federal court.)

And over at the ATF, the agency was considering whether and how to revamp its standards on armor-piercing ammunition. Thousands of pages of testimony, comments and other materials had been collected from the gun rights and gun control groups, law enforcement and wildlife groups, and more, in considering whether to expand exemptions for certain types of brass ammunition popular with hunters — particularly as an alternative to the lead ammunition that had come under scrutiny.

McCain had long championed Arizona’s program to revive the condor population and attended the first release of condors into the Arizona sky on Dec. 12, 1996. The Arizona program encourages hunters to avoid lead ammunition rather than banning it outright, as was being considered in California. The Arizona Game and Fish Department makes available this brochure online, which, unlike the NRA, states clearly that lead poisoning is a clear danger for condors and encourages hunters to use brass bullets instead. It reads: “Prove to the critics that this problem can be solved without mandatory measures.” With a looming vote on a ban of all lead ammunition in California, promoting Arizona’s less stringent program, along with a similar one, in Utah, was all the more important.

McCain’s staff had already been in touch with the ATF, but were not happy with the responses they were getting, so the senator leaped into the fray. On July 3, 2013, McCain wrote to then-ATF acting director B. Todd Jones, cautioning him that an attempt to expand a ban on non-lead ammunition as “armor piercing” would get in the way of Arizona’s program to protect condors. On July 30, the senator wrote again, inviting Jones to a meeting at the Grand Canyon to discuss the “importance of recovering the endangered California condor.”

And, that same day — July 30, according to this ATF memo — McCain placed a phone call to the agency asking to speak to Jones. Instead, he spoke to Jones’ chief of staff. “Sen. McCain was displeased that ATF had [sic] yet responded to the Senator’s letter to ATF [dated July 3] … inviting Director Jones to the California Condor meeting in Arizona on August 9, 2013.”

After the chief of staff filled McCain in about “the issues with pending exemption requests,” he said the ATF would be sending a representative to the meeting, but that that person “would be restricted on providing much dialogue on the issue.” Then, reads the memo, “Sen [sic] McCain reiterated that the meeting is about saving birds, not about armor piercing ammunition. The Senator also requested that someone with ‘decision making power’ from ATF be present.”

The timing of this phone conversation was interesting. At the time, the Senate was poised to vote on confirmation of Jones as ATF’s director. This was no routine matter. Just a few weeks before, McCain had brokered a deal with Senate Majority Leader Reid to allow the confirmation of several nominees by President Barack Obama that had been stalled by GOP filibusters. This included the nomination of Jones, who had been serving as acting director of the ATF since 2011. A McCain aide says the timing was only coincidental; that the senator was preparing for August recess, the natural time for such a meeting to take place.

True to his word, on July 31, McCain voted “yes” on the cloture vote to allow the Jones nomination to proceed, essentially helping clear the way for his confirmation. However, he abstained from voting “yes,” or “no,” on the actual nomination vote. Jones was nevertheless confirmed that day.

On Aug. 1, Jones himself called the senator “to discuss the confirmation vote from the day before.” On the phone, McCain raised the issue again of the ATF attending the August meeting in Arizona on the condor, and “reiterated that the meeting is about saving birds, not about armor piercing ammunition.”

In the end, Jones did not attend the Arizona meeting about the condor, sending ATF Deputy Director Thomas Brandon instead. McCain’s staff attempted to get an NRA representative to come to the meeting as well, but were unsuccessful. However, there was an attendee from the National Sports Shooting Foundation (NSSF), a gun rights group that is also active in opposing restrictions on lead ammunition. Other federal and state agencies also sent representatives to the meeting, and hunters groups — such as the Arizona Elk Association — also attended.

As the lead ban legislation moved through the California legislature, McCain made his voice heard again. In an unusual move, the senator made a very public plea that a sitting governor to veto the bill on his desk, in this letter to Gov. Jerry Brown.

“We must address lead exposure in condors but I strenuously disagree with a compulsory statewide ban on lead ammunition,” wrote the senator.

Gov. Brown didn’t listen. On Oct. 11, he signed the bill, and California became the first state to ban lead ammunition. It goes into full effect in 2019. The NRA and the NSSF are now working to influence the new law’s implementation.

To Chris Parish, who directs the Peregrine Fund’s condor program and is a fierce proponent of the voluntary approach to condor preservation, McCain has been a key player in trying to bridge the gap between conservation groups like his and the NRA. “I have hope that Sen. McCain … can get them to take the high road,” he says.

Indeed, the NRA’s rhetoric on the Arizona program is softer than that on California: “[S]uch programs … are preferable to a misguided and deeply flawed complete lead ammunition ban …” reads a fact sheet from the spring of 2014.

But to Jeff Miller, conservation advocate at the Center for Biological Diversity, voluntary programs do not nearly go far enough.

“Anyone who suggests that the best gauge of success for protecting condors from lead poisoning is anything other than reducing the number of lead poisonings and condor deaths is not serious about preventing condor deaths,” he said in a statement last summer.