Snap Shot Hungary: The connection between messy political funding and the rise of the illiberal state

Last week, Hungarian police raided the offices of some of the independent and much-respected civil society organizations in Budapest. Yes, you’re reading it right: “Raided” and “civil society” in the same sentence, without Putin being involved. Those of you who follow closely what’s happening in Hungary might not be surprised that the latest news from the country could easily be confused with that from Russia. You would indeed be surprised, though, to realize how much of the recent radicalization of Hungarian politics can be traced back to its messy political funding regime.

While tracing the finances of this regime can be difficult, it seems clear that the fight among political groups for resources, when not safeguarded by robust disclosure, can easily lead to significant imbalances in political competition.

Without ignoring all the other relevant social, economical and political factors that contributed to the radicalization of the country, Hungary is a great example for how insufficiently regulated and opaque political funding might contribute to turning a relatively stable democracy, with a fragile but balanced competition between political forces, into a centralized and much less democratic system. AKA the “illiberal state” dominated by one single political force that prioritizes long-term political survival over core democratic values.

But let’s start from a bit earlier.

After the transition from the socialist regime in 1989, both newly emerged Hungarian political groups and the successors of the former communist party were facing a difficult challenge: They had to (re)build their financial and intellectual “hinterland”.

In this case hinterland describes the less visible infrastructure supporting a political force that is developed and maintained behind the scenes. We all know that running campaigns takes significant financial resources, but elections are only the tip of the iceberg. Political groups, whether or not in power, have to maintain their headquarters, pay their bills and salaries, support think tanks who help them shape public policies, marketing and PR firms who improve their communications, and of course nurture a media empire with national and local news outlets who guarantee constant visibility and ever positive feedback on the party agenda.

Having such background infrastructure seems essential for the long-term survival in a political arena, and the money to support the “hinterland” has to come from somewhere.

In case of Hungary, our knowledge about the sources of money in politics is way too vague. The disclosure of party and election funding in the country is spotty at best, and corruption scandals (for a selection see K-Monitor’s daily updated media database) can never be traced back to the party treasury, in part due to complete opacity, but thanks also to the secretive nature of corrupt transactions.

What we know for sure is that the culture of donating is basically non-existent in the country, and thus, small contributions probably only constitute a negligible part of all the money that goes to political parties and election campaigns. It is therefore most likely that political contributions to elections come from the business sector and wealthy individuals, while in off-election years, parties — who officially cannot accept donations from companies — mostly benefit from kickbacks: The 10-20 percent from national or municipal tenders, subsidies and funds that are assumed to be redistributed to the unofficial party treasuries through various illegal channels.

According to political scientists, the early stages of Hungary’s recent democratic period saw a fragile, but relatively stable financial balance between major political forces. After the transition, democratic opposition groups, including the current ruling party, Fidesz, did not yet have the necessary network and experience to be able to build such a hinterland. In the meanwhile though, the Socialists, major successors of the former communist party, were temporarily unable to mobilize their former social and economic capital, as the Party suffered a huge credibility loss during the transition. Thus, the lack of resources on one side and the inability to mobilize existing resources on the other side resulted in a fragile balance between competing political forces.

By its nature, this balance was temporary, and had to be disturbed at some point.

Why and when exactly Fidesz decided to change strategy, is hard to tell, especially in the absence of reliable facts. According to many experts, Viktor Orban (currently serving in his third term as Hungary’s Prime Minister) did his best to build a strong financial and intellectual infrastructure around Fidesz between 1998 and 2002, however, it was not enough to win the 2002 elections. The Socialist Party, in the meanwhile, got stronger and managed to finally mobilize their existing capital. As a result, they won two times in a row in 2002 and 2006 and began much less cautious in their own corrupt practices.

So by the time Fidesz got back in power in a landslide win in the 2010 elections–in huge part due to the overtly corrupt nature of the eight-year Socialist administration and a leaked tape where then Prime Minister, Ferenc Gyurcsany admits that Socialists lied about the country’s economy–Orban committed to claim and control not just the Fidesz party’s hinterland, but the financial infrastructure on which all the other parties depended as well. This attack extended beyond the financial, to include the democratic checks and balances that could hinder his ability to stay in power. (It’s worth mentioning here that Hungary’s Prime Minister can be re-elected several times.)

In his attempt to create a strong background infrastructure that helps leave all other political forces in the dust, Orban systematically disabled democratic control mechanisms, made amendments to all significant laws and rewrote the country’s constitution, and launched an attack against independent watchdog institutions, the free press and civil society. He also seemed to have developed a very strong network of loyal businesspeople, who now provide for the hungry party machine.

Again: Poorly regulated political financing was not the sole cause for Hungary’s radicalization. But public scrutiny might have helped change the dynamics much earlier, and prevent Fidesz from outcompeting the rest of the political spectrum.

Attempts to reform, however, failed several times.

In 2007, for instance, a group of transparency watchdogs launched an advocacy campaign to raise attention around the problems and introduce a clear set of recommendations based on international good practices. Amongst other things, they proposed stronger book-keeping, separate accounts for parties’ elections campaigns, increased level of public funding, higher spending limits — even modest estimates tell us that ever since the transition, Hungarian political parties have always exceeded the legal campaign spending limits — and strengthened oversight. Reported spending is so clearly inaccurate, a child could tell that something’s wrong, yet no fine has ever been imposed on any of the Hungarian political parties and the respective oversight body, the State Audit Office never had strong enough powers to investigate into party reports.

The advocacy campaign had no impact.

In 2009, another coalition of anti-corruption watchdogs again tried to scrutinize election campaign spending by proposing significant amendments to the existing law – without any success. As a result, some of the watchdogs involved in the campaign decided to pull out of the unsuccessful negotiations and turn into “attack” mode, by starting to monitor campaign spending and making lots of noise around the hypocrisy of Hungary’s political funding regime.

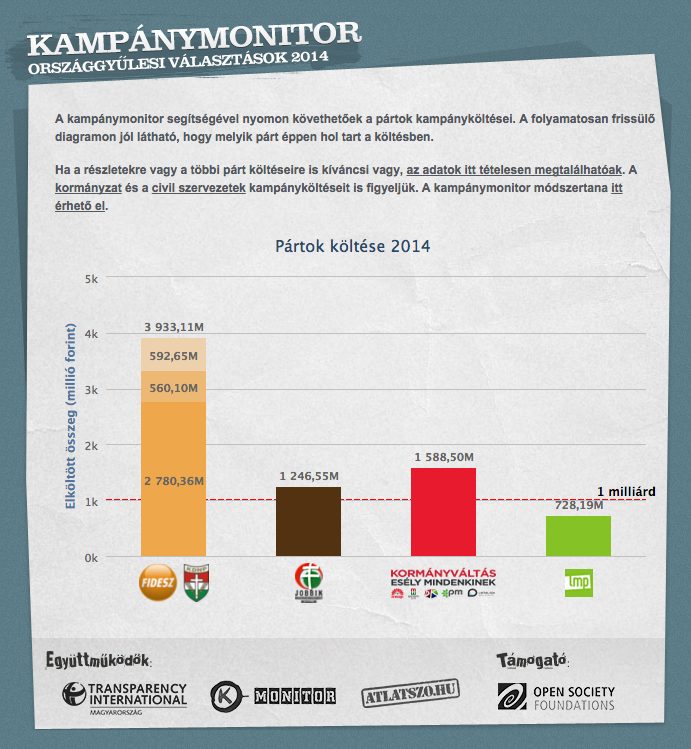

Transparency International Hungary (TI) and Freedom House created a website and began exploring innovative ways of crowdsourcing data on campaign expenditures, sharing the information on the estimated costs with the wider public through a real-time repository known as kepmutatas.hu. In the most recent elections in 2014, another collaboration of civil society groups (TI, investigative journalism web portal atlatszo.hu and anti-corruption watchdog K-Monitor, all currently being attacked by the Hungarian government) again pieced together data to demonstrate that political forces are way overspending the official limits.

But data-driven advocacy might have come a bit too late for the country.

By now, the political spectrum in Hungary is again dominated by one single force, and the state became captured by the private interests of those most loyal to the Party.

Even though Fidesz has the ⅔ majority required to make necessary changes, most recent — and in many other ways outrageous — amendments to the election system created even more loopholes and an influx of secret outside spending in the 2014 elections. As Paul Krugman pointed out, “most of the display advertising space in the country is owned by companies in the possession of the circle of oligarchs close to Fidesz (Mahir, Publimont and EuroCity)” and as a result, the attack billboards skew heavily in favor of the ruling party. And, like dark money ads in the U.S., Hungarian ads were paid for not by the party or candidate, but by an opaque outside group, the Civil Alliance Forum. Supposedly “independent,” the Civil Alliance Forum was funded by wealthy backers of Fidesz, undermining the public funding system and leaving opposition parties without major outside financial backers at a distinct disadvantage.

The tendency is pretty clear: The current Fidesz administration has no intention to shine a light on, or more strictly regulate the influence of money in politics. At the same time, civil society and the press are way too paralyzed to pick a battle, while the vast majority of Hungarian society is much disappointed in democratic institutions to want to protect them.

What’s next for Hungary is yet unclear. However, let the case of this small country in Central Eastern Europe be a warning sign that a strictly regulated and fully transparent political funding regime is a necessary (though not sufficient) condition for a healthy political ecosystem, and that large-scale corruption seriously undermines society’s trust in democratic values.