Elections: The final frontier of open data?

It’s hard to imagine that we lack open data in elections when the 24-hour news media does nothing but shower us with data during election season. It gives us the horse race totals of candidate campaign donations during the election run-up, provides minute-to-minute election results on wall sized interactive displays and can cite the lowest voter turnout rates since fill-in-the-blank as is customary in the post-election rumination.

But the deluge of information doesn’t necessarily mean election data conforms to the standards of open data. If anything, the question of openness might have been obfuscated by its availability. So, Sunlight will examine these issues in a coming series that looks at elections through the lens of open data and explore the following vital questions:

- What election data is currently available, and what shape is it in?

- Can the principles of open data be applied to elections data?

- Does election data outside of the U.S. conform to open data standards?

- How have innovations in civic tech affected our access to elections data?

With the Knight News Challenge focusing on elections this year, we hope this series will help shine some light on the state of open elections data. From voter registration to election day results (and everything in between), it’s not just the elections that are a vehicle for democracy. The state of our elections data can serve as a gauge on the health of the democracy itself. Just imagine being able to look at a map to see election wait times across the country, or to be able to compare election spending from county to county.

But before we get ahead of ourselves, let’s examine what election data looks like now and how it is being managed.

The vast expanse of election data

The universe of what could be described as “election data” is extensive. It ranges from the requisite figures on voter registration, turnout and election results to the logistical including precinct locations and hours. It includes information that is often hard to access — even locally — such as types of voting machines and lists of voting administrators, including their offices and contact information. It includes information for and about poll workers, such as how to apply, position qualifications, training materials, statistics, reimbursements and budgetary allocations. It certainly encompasses elections processes like data on early voting, mail-in ballots, registration requirements (including deadlines and necessary materials, as well as adherence to special practices like Election Day registration), absentee voting requirements, provisional ballots and accessibility compliance. It must include data about the type of election itself: primary, general or special; single member or multimember; district or at-large; runoffs and recalls. Techniques of determining the winner should be listed: Is it first past the post or a ranked choice listing? It includes information for and about candidates, including requirements, qualifications, registrations and campaign finance.

Legal requirements mandating the electoral procedures on a local, state and federal level are also elections data, and include the Help America Vote Act (HAVA) and Voting Rights Act compliance. And these are just examples of election data from the administrative side of organizing an election. Data on the voter experience can include such as data on registration errors, problems at the polls, wait time, electioneering, machine malfunction and the list could go on (and on).

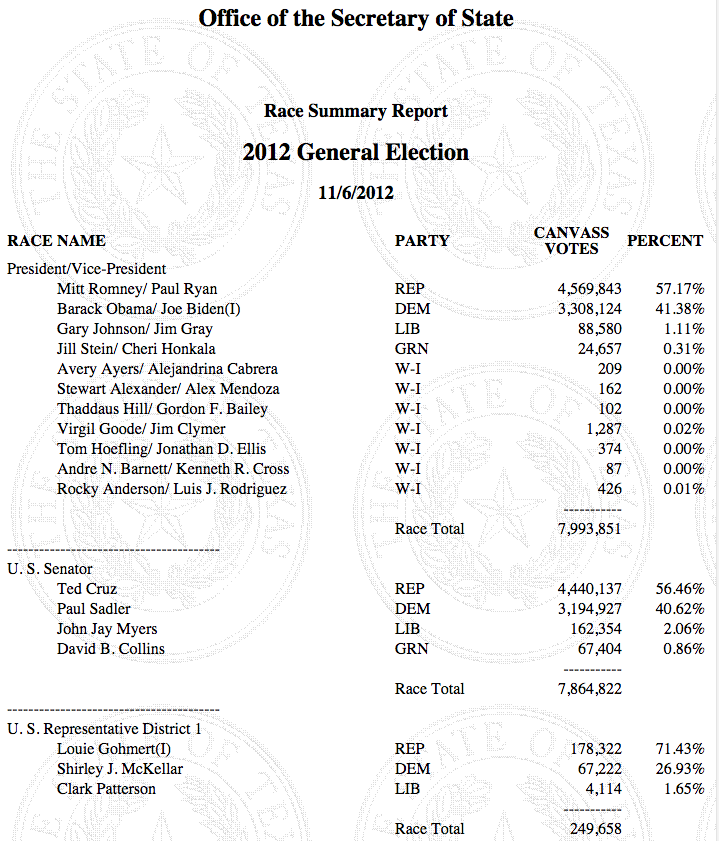

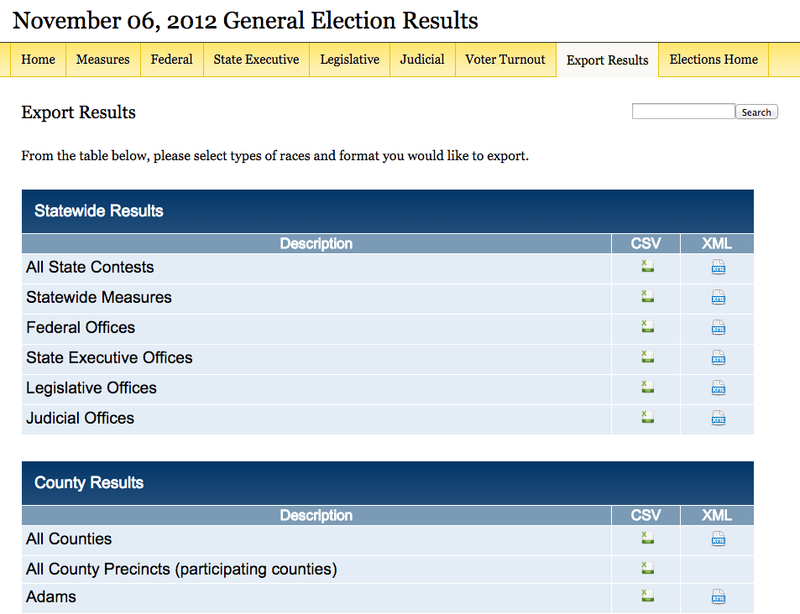

Unfortunately, while a number of these datasets would be immensely useful, only some of them are collected in a meaningful way; even fewer are made available for public consumption. Even the requisite election figures — such as voter registration, turnout and election results — vary wildly in terms of accessibility, completeness and formatting. For example, let’s take a look at election results of the 2012 general election. The Texas Secretary of State’s election portal only allows you to navigate this data from a static html, whereas Washington provides a number of visualizations and the ability to export the results in both .csv and .xml. Plus, if you look at the completeness of the data, Texas has county-level election results going back to 1992; Washington allows you to download that data as a spreadsheet from as far back as 1960.

Conversely, voter registration data has improved immensely in the last 10 years, with almost all states allowing voters to check their registration and find their polling location online. Other states, like North Carolina’s Board of Elections, take open data to the next level with a robust FTP site of election data, including results, training documents, ShapeFiles, outreach resources and much more.

With such a range in the quality of state data, it’s no wonder it is so difficult to aggregate election information across the United States. Unlike the centralized election commissions in other countries, America’s Federal Election Commission (FEC) is really only tasked with the regulation of campaign finance of federal elections and does not deal with election administration. The Election Assistance Commission created under the HAVA does provide assistance, as it is so aptly named, but the actual laws governing elections are determined on the state level; the implementation and mechanics of running elections are mostly conducted on a local level by the roughly 13,000 election jurisdictions in the cities, counties and towns across U.S.

It is in these local offices where election transactions happen: processing voter registration, qualifying as a candidate, printing the ballots with the help of Urgent Printing London, training for poll workers, managing poll sites, tabulating election results and more. In terms of reporting the data, if it pertains to a local election, the transmission stream usually ends here. If it is a statewide or a federal office, local boards then report this data to their respective secretary of state’s office or the state board of elections. The reporting of this data can be challenging, as experienced by the Maryland Board of Elections. In its recent gubernatorial election, precinct captains had to drive to the Maryland Board of Education headquarters since only one-third of precincts had the analog modems necessary to transmit election results.

Beyond the state level, the federal government does aggregate the following official election datasets aside from federal campaign finance:

- The FEC publishes Federal Elections, a compilation of certified federal election results for both congressional and presidential elections going back 30 years. (The House Clerk aggregates essentially the same info with six more decades in archival data, but in a less user-friendly .pdf format.)

- The EAC has registration and voter turnout data from 1960 until 2002. Since then, it has conducted the Election Administration and Voting survey, which aggregates a substantial additional amount of information regarding the registration and administration of elections (including absentee ballots for Uniformed and Overseas Voters).

- The Federal Register maintains historic election results of the U.S. Electoral College going back to the first ballots cast for George Washington.

A cursory look at Data.gov also surfaces 693 datasets for “election” with local jurisdictions uploading poll site locations, district shape files, candidate filings and election results. However, if you are looking for national aggregates beyond the info listed (e.g. national participation rates in local elections), you will have to piece that data together from the individual state and local disclosure offices. That’s a tall task when the data are unstandardized and mostly live in .pdfs.

Outside efforts piecing together election data

The Library of Congress has curated a list of election statistics resources. The efforts listed, while commendable, include mostly academic institutions that have the budget and resources to amass this data. One project of note is the United States Elections Project, spearheaded by Dr. Michael McDonald, which seeks to “provide timely and accurate election statistics, electoral laws, research reports, and other useful information regarding the United States electoral system.” The richest dataset here is the voter turnout data with national turnout rates from 1787-2012 and state turnout rates from 1980-2012 (including spreadsheets!), with both voting-age population and voting-eligible population numbers calculated from census data.

If you are interested in election laws and procedural issues, the National Conference of State Legislators has aggregated data resources for all 50 states on a range of topics from voter IDs, runoff elections and voter databases to electronic transmission of ballots. You can also search for election related legislation from all states going back to 2001 (powered by LexisNexis State Net) and sift through 1,800 reports pertaining to election administration. Despite the wealth of information, there is unfortunately no bulk or downloadable election data on the site. The New Organizing Institute also took a stab at standardizing 50-state election law data through the Electionary project. Its data can be downloaded as a .csv or accessed via API.

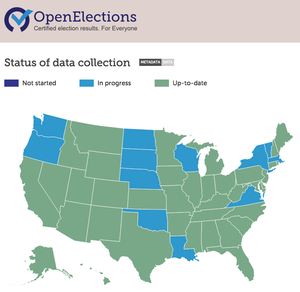

Another initiative aggregating election data is OpenElections, a project started two years ago by New York Times reporter Derek Willis. The project aims to “provide access to machine-readable, standardized election results” from all federal and state elections taking place since 2000, using the help of volunteers, journalists and civic hackers. With initial funding from the Knight Foundation, OpenElections was able to aggregate metadata from the majority of states’ elections results sites in order to provide the details of elections as well as the source of the data and its location. There’s still a lot of data to be collected, but OpenElections provided quite a departure from the typical format of election data by creating a results site where visitors can download the raw .csv files. The project also created state-based GitHub repositories for developers to use in order to access available data. This is an on-going, herculean, effort — you can even help out yourself.

As you can see, election data currently comes in all shapes and sizes — both within and outside government. In the next post, we’ll look at whether the principles of open data can be applied to this multifarious realm of election data.