Unlike potential opponents, Ted Cruz starts playing by the presidential rules

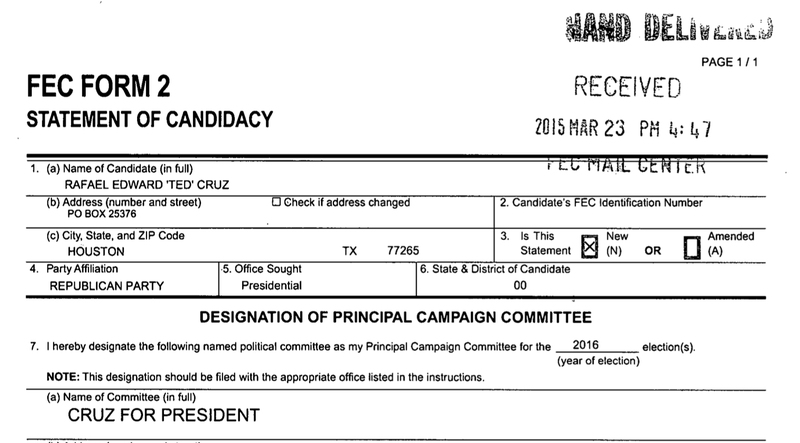

Shortly after midnight last Monday, Texas Republican Ted Cruz tweeted four magic words: “I’m running for President.” Under our campaign laws, this subjects the senator to restrictions and obligations expected of all candidates running for federal office.

Specifically, Cruz cannot ask for contributions of more than $2,700 from individuals for his presidential primary run, nor may he solicit contributions of more than $5,000 for outside spending groups, like super PACs. He’s barred from controlling a 527 organization, those shadowy political organizations that don’t report their activities to federal or state campaign regulatory agencies. He can’t ask foreigners for money, nor can he raise money from corporations or labor unions. He’ll have to file regular reports with the Federal Election Commission, detailing whom he’s taking money from and what he’s spending it on, whether it’s salary for campaign aides, polling, fundraising expenses, travel or other expenditures.

Yes, he’ll be able to court bundlers — those well-connected donors who can reach out to their networks and package tens of thousands of dollars or more. And yes, he most likely will discover that some longtime ally or aide has left his side to form an entirely independent super PAC to help Cruz, hopefully with three or four but no less than one very deep-pocketed donor who can write seven-figure checks. But let’s take a moment nevertheless to salute him, the first major presidential candidate from either party to start playing by the presidential rules.

By contrast, all but declared candidates like former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush can, and do, raise money in huge chunks. Because Bush has not uttered, tweeted or otherwise expressed the magic words, he’s able to ask donors for contributions of $25,000, $100,000 or more for his Right to Rise super PAC (Sunlight’s Party Time shows quite a few examples). Part of Bush’s strategy for winning the nomination is a campaign of shock and awe fundraising; should he declare his candidacy, he’d have to leave the six- and seven-figure solicitations to others.

A trio of super PACs — Priorities USA Action, American Bridge and Ready for Hillary — are promoting Hillary Clinton. One of them, Ready for Hillary, successfully fended off a complaint to the FEC last month over its purchase of the mailing list compiled by Clinton’s last presidential campaign. The FEC concluded that the sale by Clinton’s 2008 campaign, which comprised names of her donors and supporters, to a super PAC promoting her 2016 campaign did not require Clinton to register as a federal candidate.

That decision has allowed Clinton — and the two floors’ worth of close associates she brought with her from the State Department — to continue her work with the Bill, Hillary and Chelsea Clinton Foundation undisturbed, an organization that takes funds, sometimes in multi-million dollar chunks, from foreign governments, foreign corporations and foreign individuals, among others.

Neither Bush nor Clinton are private citizens, but not even holding office is an impediment to stealthy fundraising. Sitting governors like Wisconsin’s Scott Walker, R, can lead their own 527 committees, named for the section of the tax code under which they’re organized. Our American Revival, Walker’s 527, can raise funds in any amount from individuals, corporations and labor unions (though, given Walker’s policies, he probably won’t be expecting much support from that quarter). The organization’s registration with the Internal Revenue Service says that its purpose is to “lead a revival of shared values” by “limiting the size and scope of the federal government.” But, as the Washington Examiner more accurately reported, Our American Revival lets Walker “raise money and promote his potential candidacy in advance of an official announcement.”

The 527 is actually a step forward for Walker — it will have to disclose its donors, albeit to the Internal Revenue Service. During the 2012 effort to recall him, Walker raised money for the Wisconsin Club for Growth, a dark money group that supported him, as Michael Isikoff recently reported for Yahoo! Politics. Walker’s aides prepped the governor by telling him to stress to donors that Wisconsin Club for Growth could keep their identities secret.

By being the first major candidate to publicly acknowledge his presidential ambitions, Ted Cruz also became the first to be bound by the nation’s campaign finance laws. When will his rivals follow him?