NASA’s EPIC photographs: Sunlight and open data on a global scale

Sunlight’s Outside the Beltway series was set up to shine a light on exciting developments in the open government world beyond Washington. But this week we’re taking it a step further and highlighting a new open government initiative that is literally out of this world.

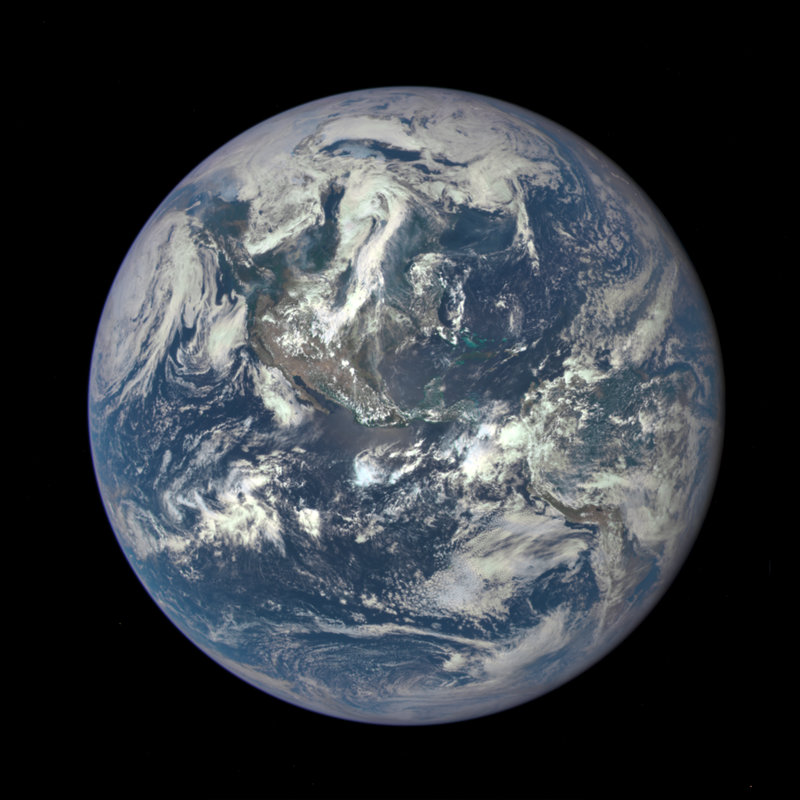

On December 7, 1972, the crew of the last manned lunar mission captured a simple photograph through a small window in their spacecraft: the Earth, bathed in sunlight and suspended in darkness. The image, known as the “Blue Marble,” showed humanity its home from an entirely new perspective — and it is thought to be the most reproduced photograph of all time.

Since that iconic picture was first published, NASA has released plenty of follow-ups. But the subsequent “blue marble” images have actually been composites stitched together from individual satellite images that each capture only a portion of the Earth’s surface. That is changing, though, with a new NASA mission that will share all of the data and images it collects online.

In February, NOAA launched its new Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR), which reached its final position more than a million miles away from the Earth last month. It will orbit the Sun at Lagrange point 1, a location where the gravitational pull of the Earth and the Sun are in balance, which allows it to maintain a fixed position between the two moving bodies. Although the primary purpose of the mission is actually to monitor weather conditions in space, DSCOVR’s orbit position between the Earth and the Sun means it is also perfectly situated to capture images of a fully sunlit Earth.

Last week, NASA released the first of its new “blue marble” images — and it is just getting started. Beginning in September, the Earth Polychromatic Imaging Camera (EPIC) will capture an image of the Earth every day, which NASA will post online within 12 to 36 hours. Think about that. NASA is able to take a photograph of the entire planet from a million miles away, beam it wirelessly back to Earth and then post it on a website — all faster than members of Congress would be required to disclose large campaign contributions under even the most ambitious reform plans.

The DSCOVR mission combines three things we love here at the Sunlight Foundation: open data, clever names and (actual) sunlight. We know that when governments share information openly, they can help inform the public, but NASA’s EPIC images show us that they can sometimes even delight.