What kinds of data do school districts release?

Last week, Sunlight asked whether school districts had policies in place to govern releases of aggregated or de-individualized datasets. The short answer, it seemed, is no. Few school district policies bother to mention releases of data to the public; of the ones that do, most emphasize restrictions rather than openness. Over 50 U.S. cities have some sort of open data policy, but out of all those cities, only two — Boston and Cambridge — have any language discussing education data (and that language focuses on privacy, not transparency). Thus, the next question to ask is: Regardless of policy, what datasets are school districts releasing anyway?

It’s important to remember that not all school data should be released, in order to protect individuals’ privacy. However, there are many datasets school districts almost always collect that do not identify individual students and can be very helpful to people interested in education, whether they’re students, politicians, teachers or community advocates. These datasets include information related to student achievement in an entire school, like graduation rates, state or college-entrance test scores, and discipline statistics. They include “snapshot” information about a school overall, like individual school budgets, enrollment and demographic data, school improvement plans, and student, teacher or parent surveys. Lastly, they include information set or collected solely at the district level, like systemwide budgets, school catchment areas and larger community surveys.

First, do the data exist?

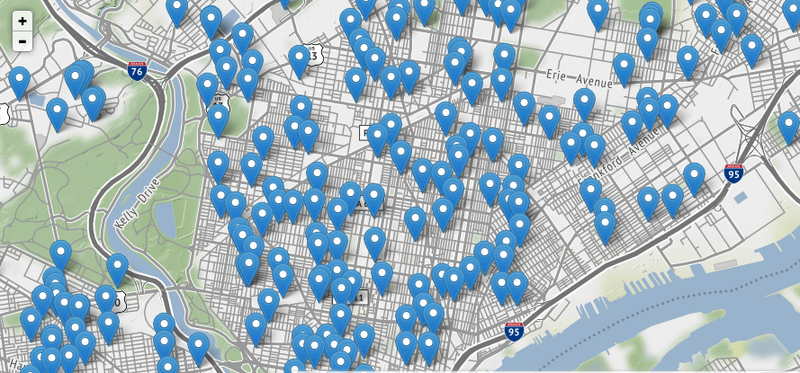

The first step in determining whether datasets are open is seeing whether the data exist — not merely in a principal’s filing cabinet, but on the web for anyone to access. For the most part, the above array of datasets can be found on school district websites. NYC OpenData admirably provides an “Education” category compiling SAT scores, GIS school boundaries, enrollment statistics, class sizes, graduation rates and other similar files. Although some of the data on the New York City portal (like school safety reports) appear out-of-date, the New York City Department of Education earns credit for providing data back-ups — an easy-to-find data page gives links to most of the datasets we’ve listed, and an additional page under “Performance & Accountability” helps guarantee that the datasets can be found.

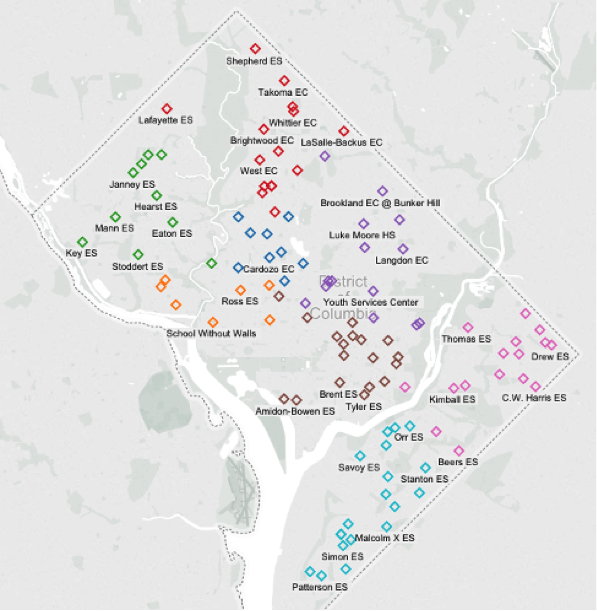

Other big school districts also make an effort to put datasets online. District of Columbia Public Schools provide links to data by school and for the whole system, and provide more websites for data on budgets and charter schools. Chicago Public Schools has also compiled many datasets into a centralized online site (with a few more datasets, often out-of-date, on the city of Chicago’s open data portal). Still other releases are less comprehensive. Baltimore City Public Schools shows changes in the funding of individual schools, but not the cause of those changes or the complete breakdowns of individual school budgets, raising some interesting questions. (How, for instance, did Digital Harbor High School lose $555,709 in general funds despite an enrollment decline of only 48 students?) Elsewhere, school districts assume that different governing agencies will release the data instead. The Los Angeles Unified School District directs searchers to California’s DataQuest, with little data on individual school budgets available. By contrast, Cambridge Public Schools, home to some 7,000 students, clearly strives to put data online: District budget information comes with a solid archive and school improvement plans are listed one-by-one. Sometimes, though, Cambridge’s online datasets are a few years too old to be of much use — the last report listed under “CPS Student Benchmarks” is dated 2007.

Are the data machine-readable?

It is possible to find a lot of education datasets, at least if you’re willing to search many sites and don’t mind the occasional year (or nine) of delays. But open data is about more than simply online data. One of the characteristics of open data that Sunlight frequently highlights is machine-readability — in other words, whether datasets are in a format that makes them easy to search, copy, convert and process, especially if one is handling data in large quantities. Machine-readable formats make many apps, visualizations and research projects easier, or possible. Although many cities put datasets online, far fewer take the more complex steps of making data machine-readable or available in bulk. Unfortunately, a similar decline is seen in data released by school districts.

New York, as well as Montgomery County Public Schools, releases some datasets on a portal developed by a third party, which often ensures machine-readable formats. Try exporting GIS data on New York City school districts, and you will find a series of easy-to-use formats like CSV or JSON. Similarly, the Washington, D.C., Los Angeles and Chicago school districts will provide many datasets in a relatively easy-to-use Excel format. This machine-readability, however, is hardly consistent. Washington, D.C., puts survey data in large and clunky PDFs and buries other information — such as on discipline, student satisfaction, school resources and demographics — in PDFs and HTML tables on school “profile” pages, making the data harder to access and utilize. School districts in Los Angeles will provide pictures of maps, but not the JSON files that are easier to manipulate. For some files, LA school officials tell site visitors to use “[t]he Google Chrome browser … to save the SARC report as a PDF.” Such advice is a far cry from the machine-readability that makes data easily available for use by the public.

Are the data in bulk?

Making data available in bulk is another key feature of open data. Bulk access means ease in handling larger groups of datasets; in an education context, it might involve having attendance rates, sorted by grade, by school and by year, all in a single file. This kind of access makes comparing schools or identifying trends significantly easier, and maximizes the potential for data to be reused apart from where it was first posted. Unfortunately, bulk access is also much less present in school district data releases.

San Francisco is a prime example. A quick glance at the US City Open Data Census will show that the city of San Francisco typically does an excellent job at providing data in bulk. The San Francisco Unified School District has a much spottier record. Graduation rates are on separate pages for the district and for individual schools, and don’t seem very easy to download. A search for state test results might lead to links for dozens of separate PDFs. If you’re looking for School Quality Improvement Index data, your best bet seems to be on the websites of each individual school — all 147 of them. There is a similar lack of bulk in other school districts: Whether you’re looking for AP participation in Fairfax County or attendance rates in Baltimore City, data often appear separately for each school, rather than in any more aggregated, bulk files.

How to improve?

Neither school district policies nor city laws mandate open releases of education data. In a sense, then, it’s remarkable how some education datasets appear in bulk and machine-readable formats in the first place. Indeed, the New York City Department of Education seems to stand out with consistently up-to-date, machine-readable, bulk datasets released for public use.

For most other school districts, however, plenty of improvements are needed to make basic education datasets more open. Over the past 10 years, a slew of cities and states have steadily revised and strengthened policies to provide open data, often in keeping with Sunlight’s Open Data Policy Guidelines. Some of these municipal data releases have had huge impacts, from campaign finances to responses to blight and precautions against fires. School districts could experience similar benefits, but designing new technologies is unlikely without machine-readable data formats, creating compelling visualizations is painfully hard without bulk data access, and interpreting education trends is nearly impossible if the right data barely even exist online.

To improve, school districts must follow the successes of city governments that have led in the movement for open data. New policies should call for regular and proactive releases of education data, and school board rules or superintendent regulations should specify a range of datasets that will be uploaded and kept up-to-date on the web. Such data shouldn’t be dumped on individual school websites or in enormous PDF files, but should be provided in machine-readable formats and accessible in bulk to enable effective use by the public. More open education data could thus help school officials identify problems, spark new technologies to assist teachers and students, and empower local education advocates. But at least as importantly, greater openness from schools could better connect all students and adults with their local governments, and shine a brighter light on education’s essential role in building and sustaining vibrant communities.