Using data to track police response to sexual assault

Cases of rape and sexual assault contain deeply private information, but public data is available to help hold police accountable and provide guidance for better policing. And we can learn a lot from the recent investigation by the Department of Justice (DOJ) investigation into the Baltimore Police Department (BPD), which documented a number of serious problems with Baltimore’s policing.

As with the Justice Department’s work examining racial bias in policing, investigators looked at both individual cases and broader statistical trends to evaluate BPD’s policing for evidence of gender bias. However, rather than looking at stop and arrest data, investigators evaluated gender bias by looking specifically at sexual assault, a crime which disproportionately affects women. While members of the public can’t access individual cases the way the federal officials can, the department’s use of public data to assess BPD response to sexual assault provides a model that any of us could use.

The techniques that the DOJ employed to evaluate police response to sexual assault were fundamentally different than those that they used to evaluate racial bias in policing. First, investigators found themselves looking for police failure to act — failure to investigate, failure to evaluate held evidence and failure to arrest — rather than excessive police action.

Second, while we can identify racial profiling using the public stop, search and arrest data which is becoming increasingly easy to access, most data about sexual assault cases cannot be publicly released. However, by following the DOJ’s use of data that is held in federal datasets like the FBI’s Uniform Crime Report, or by submitting a public records request for data which does not contain personally identifying information, we can nonetheless find ways to use data to see how individual law enforcement agencies respond to sexual assault.

Using public data to evaluate sexual assault response

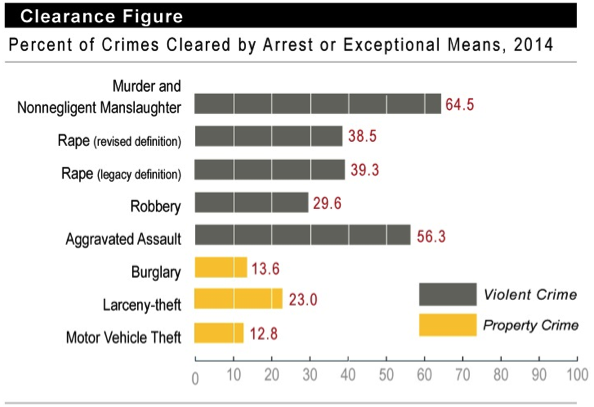

While most police information about sexual assault cases is protected, there is some public data that can be used to learn more about how police departments handle sexual assault cases — it just might not be released directly by the local agencies themselves. The Uniform Crime Report (UCR), one of the nation’s most comprehensive crime databases, collects information from all U.S. law enforcement agencies about violent crime and property crime occurring within their jurisdictions. As a result of the UCR requirements, all law enforcement agencies provide information about the number of allegations of rape that they have received. They also provide information about the number of rape cases that they have determined were “unfounded,” which means either lacking in credible evidence or false, and information about the number of rape cases that concluded with the arrest of a suspect. The percentage of cases in each crime category concluding with an arrest is known as the department’s “clearance rate” for that category.

Using UCR data about Baltimore’s sexual assault cases allowed federal investigators to make certain critical observations about the department’s practice. Specifically, investigators used UCR data to track the average outcome for reports of rape lodged with the BPD.

- Investigators looked at clearance rates for sexual assault reports and evaluated the proportion of reports which were closed due to the arrest of a suspect.

- DOJ investigators examined BPD’s clearance rates for sexual assault reports and found that fewer than one in four of its rape investigations are closed due to the arrest of a suspect. This is a rate, they observed, which is roughly half of the national average.1

- DOJ investigators reviewed the proportion of rape reports which were dropped because they were determined to be unfounded.

DOJ investigators were able to draw on local journalistic inquiry as an aspect of their investigation. To evaluate whether BPD was properly investigating reports of rape. In June 2010, the Baltimore Sun reported that BPD patrol and detectives had classified more than 30 percent of their rape cases as “unfounded.” In context, this revealed that the department’s rate of determining rape reports to be unfounded was five times the national average.

While DOJ investigators were able to use BPD’s own data for these questions, The Baltimore Sun simply used public UCR data. This data, while not immediately available in detailed form online, is available by request. Our own emailed request to the Crime Statistics Management Unit received a quick and helpful response, and we received national UCR data on clearances and unfounded rates for 2013 and 2014, the most recent full years available. (Attachments from our correspondence are shared below.)

Using 2014 UCR data on clearance rates and unfounded cases to look at Baltimore, it seems clear that The Baltimore Sun report had a real impact on BPD’s crime reporting.2 Rather than identifying too many rape cases as “unfounded,” BPD in 2014 reported that there were no unfounded rape reports. However, BPD’s reported clearance rate for rape cases in 2014 was 10.6 percent. That’s a clearance rate of about half of what The Baltimore Sun reported in 2010 — or one-fourth of the national average for clearances in rape cases. (Interestingly, there may be a relationship between these two changes. This reporting guide issued by the Washington, D.C. Metropolitan Police Department, indicates that “unfounded” cases are deducted before the calculation of a clearance rate, so Baltimore’s previously higher number of “unfounded” cases may have also artificially inflated their clearance rate.)

Requesting statistical information from your police department

The information on sexual assault cases which is available through the UCR certainly helps to give a picture of the way that police responds to this type of crime, but for other relevant data it will probably be necessary to ask police departments directly.

Discover the proportion of cases which are open relative to the number of cases which are reported. A high number of open cases suggests that police are not aggressively investigating reports of rape.

A high average proportion of open sex offense cases means that it’s likely these are not being actively investigated. During their investigation in Baltimore, investigators were able to access BPD’s own data about the status of their cases. They discovered:

BPD allows more than half of its rape cases to linger in an “open” status, often for years at a time, with little to no follow-up investigation. … According to BPD’s own data, between 53 and 58 percent of its sex offense cases were in an “open” status each year between 2013 and 2015.

Since data on the number of open cases in any one year is unlikely to contain private, personally identifying information (unless there is an extremely small number of cases, as might be true for smaller towns), you should be able to ask your local police department for an answer to that question. However, if your agency takes part in the federal National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS) reporting program – and all law enforcement agencies in 15 states, plus many others do – you can use public NIBRS data to learn about the length of time that cases in each reporting category are open. Datasets covering 2010-2014 (the most recent year of release) are available here at the National Archive of Criminal Justice Data website.

Discover the number of untested rape kits in your police agency by submitting an open records request.

Rape kits make it possible to identify suspects using DNA evidence. However, where a victim provides physical evidence but that rape kit is not tested, the evidence can’t help further the investigation. A failure to look at evidence that’s already been collected suggests a failure to investigate properly. Where rape kits are routinely not tested in rape investigations, that suggests a systemic failure to investigate rape cases properly.

In Baltimore’s case, DOJ investigators found that rape kits were tested in only 15 percent of cases involving sexual assaults of adult victims between 2010 and 2014. Despite ongoing departmental reforms during this period, federal investigators found this trend did not improve in the following year: Between January and September 2015, BPD detectives requested testing of rape kits in only 16 percent of adult sexual assaults. Had BPD tested more of their rape kits, perhaps more sexual assault could have been prevented: The DOJ “reviewed numerous cases of forcible rapes of women by strangers that presented circumstances suggesting there might be serial rapists involved.” By failing to test 85 percent of their collected rape kits, BPD failed to prevent future assaults by individuals. In testing rape kits, communities have found frequent evidence of serial assault, links to other crimes and even to assaults in other jurisdictions.

The failure to test rape kits is a frequent failing of police departments across the U.S. In 2015, USA Today helmed a project to obtain records from 1,000 of the nation’s 18,000 law enforcement agencies and found that there were at least 70,000 untested rape kits in those 1,000 agencies alone. Where initiatives have sprung up to “end the backlog” and test the rape kits presently just sitting in storage, analysts have found new evidence of the activity of serial rapists. One such study in Ohio found that over 50 percent of rapes examined with the newly tested kits were associated with serial rapists, while Detroit’s effort to address its testing backlog uncovered 21 potential serial rapists within the first 153 kits that were tested.

To discover the percentage of rape kits your law enforcement agency has tested, submit a public records request seeking that information for a specific time period. You may also be able to find your agency’s current rape-kit backlog through USA Today’s database (find on page with the phrase “search police departments”). End the Backlog, a project devoted to achieving the testing of all of the nation’s rape kits, has an Accountability Project with more information about local level work.

Partnership for data quality audits

Even where data is accessible, it can’t be used effectively if it has been collected or maintained in problematic ways. The Justice Department called out BPD’s data collection methods in the area of sexual assault particularly:

We were troubled by the fact that BPD was unable to provide us with responses to our requests for basic data about the victim and suspect population, the incidence and nature of cases of sexual assault reported to and handled by the department, and the incidence of cases of sexual assault involving BPD officers.

An approach which Baltimore used even before the DOJ investigation suggests another method that could be used to evaluate data quality for sexual assault cases.

Work with your local SART to conduct an audit of your police department’s determination of unfounded assault claims.

Following The Baltimore Sun’s reporting which established that BPD had unusually high unfounded rates, the mayor called in the city’s Sexual Assault Response Team (SART) in order to evaluate the cases that BPD had labelled unfounded. The Baltimore SART found that BPD had misclassified over half of the unfounded cases, providing expert oversight of a key problem which was later also highlighted by the DOJ’s report.

Although SARTs may not yet perform police oversight in many cities, the SART is an organizational form which has proliferated across the United States in the last decades and they’re now present in many communities across the country. Where cities have concerns about the accuracy of police response to rape reports, using a local SART to perform this type of audit can provide more information about the accuracy of police response to sexual assault victims.

Using public data to assess police response to sexual assault

Despite the challenges of private and protected information in sexual assault cases, it is still possible to use existing datasets to hold police accountable for their investigative practices. Using UCR data, seeking public statistics from the police department, and partnering with a local SART to perform an audit of police cases may not provide all of the details needed to understand how police are working with sexual assault cases. Nonetheless, these techniques provide the bones of an approach which could be used to assess gender bias in policing across the country – a problem that the DOJ investigations reveal is most certainly a bigger issue than we have yet begun to realize.

Written with assistance from fellow Joy Namunoga.

1 In 2013, the FBI revised the definition of rape for the purposes of UCR reporting. (Back to top)

2 If you’d like to clean up these text files for more analysis, the four datasets are available here: Unfounded 2013, Unfounded 2014, Clearances 2013, Clearances 2014. (Back to top)