In Kansas City, residents have a new friend on Facebook: an open data chatbot

On June 19, Open Data Kansas City officially launched a new bot on Facebook to try to make its open data portal more accessible to non-technical users. The chatbot converses with Facebook Messenger users to help them find the most useful data on what they care about in city government.

Open Data KC’s chatbot isn’t the first bot designed for public policy data access — the Chicago advocacy group Citizens Police Data Project has a Twitter bot for officer complaint data — but it is one of the first official efforts by a city government to make open data more accessible through Facebook.

The new initiative in Kansas is a great example of Sunlight’s work on how cities can make open data easier to understand and use for the public. Kansas City’s piloting a new approach to addressing this challenge is promising.

Eric Roche, Kansas City’s Chief Data Officer, had the idea to build the chatbot after discussions with city leadership during yearly reports on the city’s open data progress.

“The Mayor, more than once, has said ‘open data is hard to use’,” said Roche in a phone interview.

So Roche’s goal became to build a tool that’s easy for those who aren’t developers or data scientists to understand and navigate on a familiar platform.

“The one user that keeps sticking out in my mind – it’s a home association president or neighborhood leader that knows enough to know there are 311 calls and code violations, and they want to know which properties in the neighborhood have those,” he said.

“That’s a really difficult thing to find on open data if you don’t know the terms and lingo. But with this tool, they could type in code violations and find them by neighborhood. And connect with the right datasets and visualizations.”

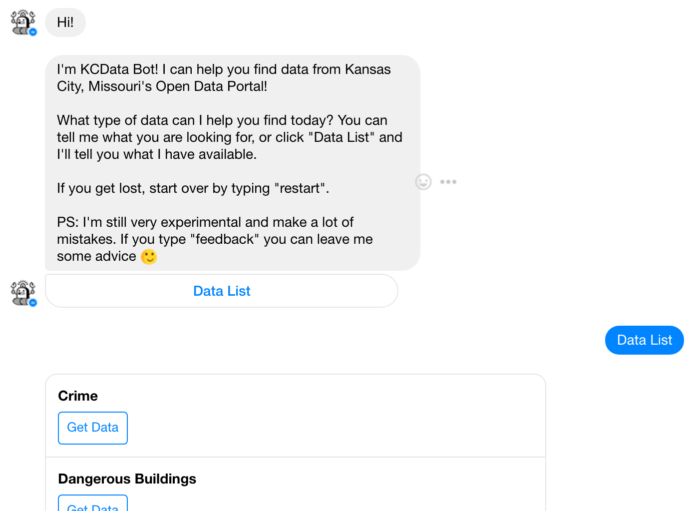

My test of the chatbot showed there’s both real utility to it and room for improvement.The chatbot excels at recognizing common data categories and directing users to potentially useful datasets. It readily recognizes queries like “building codes,” and more practically, presents a user with several useful choices within a category, such as “building codes,” “business licenses,” and “market value study.”

This is by design – Roche says he hard-coded popular and “malleable” datasets – that is, ones that can answer a variety of specific queries – as default answers.

The chatbot still can’t recognize more specific queries, however, such as “dog license.” When this happens, the program offers the user a choice to browse all datasets, use the Open Data KC website’s search function, or submit feedback.

Roche acknowledges these current limitations to users: the chatbot’s introductory message includes the disclaimer: “PS: I’m still very experimental and make a lot of mistakes. If you type ‘feedback’ you can leave me some advice,” along with a “smiley-face” emoji.

Just as the chatbot seeks to be user-friendly, its production, at least in its current stage, was developer-friendly. Roche didn’t need a team of software engineers or data scientists; he built it himself over the course of several weeks at “Code for Kansas City” meet ups in his free time.

Roche usually works in the programming languages R and Python. But to build the chatbot, he used the platform Chatfuel, which makes it possible to build AI bots for Facebook messenger without the builder doing any explicit coding. For now, Roche’s primary goal is for it to automate common questions and inquiries that his office gets from Kansas City residents.

“If you asked me for ‘crime data’, I’d ask, well, ‘raw data or map, etc.’ I wanted to script some of those conversations – and when I say script, I really do mean script! There’s no complex machine learning,” he said.

So while building the chatbot was no small feat, production of similar bots may be in reach for other city governments whose open data departments have limited time and money.

For his part, Roche sees the chatbot as a proof-of-concept. If Open Data KC sees consistent use of the chatbot from residents, Roche would like to make a major expansion of its capabilities.

“If it was a big success, I’d go to local Code for America and data meet-ups and see if there’s a group of people who’d want to build out a ‘2.0’ that’s getting closer to a machine-learning model,” he said.

In the meantime, Chatfuel makes it easy to track what users are searching for and not finding, and Roche is using Google Forms to organize suggestions that users make through the chatbot.

Roche views the evaluation process as “totally exploratory” and acknowledges he doesn’t know where it’s going to lead. He doesn’t have an explicit marketing plan or a budget for the chatbot, but might put some Facebook advertising dollars behind promoting it.

Given Facebook’s massive user base, Facebook chatbots could become a major new point of citizen access to open data – but only if these interested citizens find the chatbots on Facebook and like using them. If Kansas City’s chatbot and projects like it prove successful, they could prove a valuable tool for cities everywhere for facilitating community use of open data.

“It’s a true experiment,” Roche said.

We hope it’s not the last. Open data isn’t always easy to find, access, and use. For the city hall open data programs to matter to residents’ lives, it needs to be.