How opening city data can support racial justice

This weekend, I’m headed to the inaugural Data for Black Lives conference at MIT’s Media Lab for three days of focused discussion about how data science can create concrete, measurable change in the lives of black people and marginalized communities. On the agenda for the conference are conversations about data’s role in the use of force by police, political power, and public health, as well as how well people of color are represented within the field of data science.

I’m looking forward to discussing all of these issues, with a particular focus on how open data from city governments is part of this work.

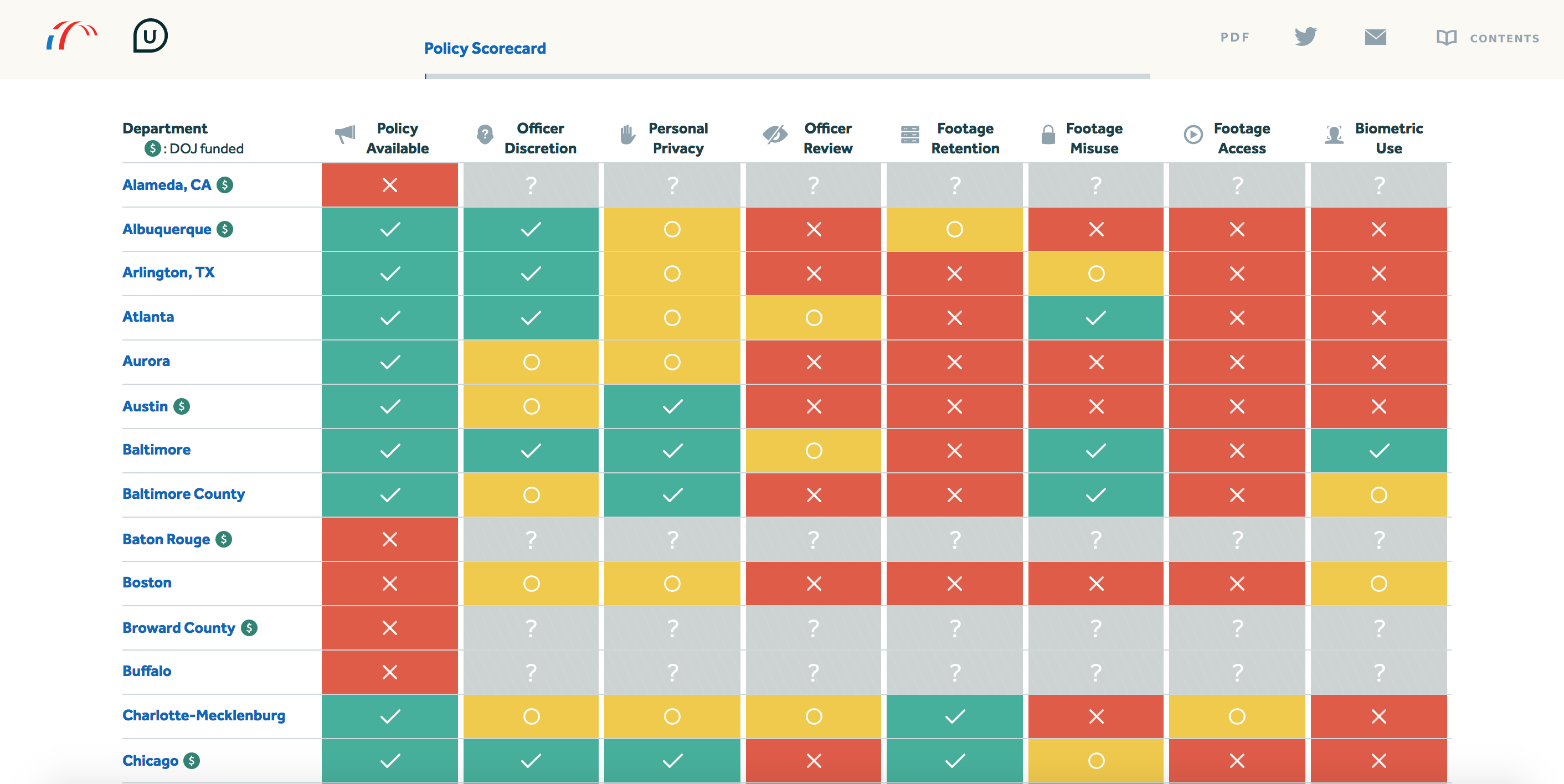

Cities collect data on food deserts, emergency room visits, and 9-1-1 responses that are relevant to conversations about the health of black communities, for example. Cities and states are stewards of video footage from police body cameras, they collect data on traffic stops, and are involved in incidents of “walking while black” or ticketing, and each of these contribute to our understanding of racial profiling or the use of force by law enforcement. Local election boards in cities collect information about voter registration and turnout that underpin and inform public conversations of political power and representation.

In this sense, municipal open data plays an important part in understanding inequality. Understanding inequality, however, is not enough to end it.

Advocates for equity can and must do more to demand more transparency from local authorities by working with cities to open up data, close information gaps in their communities, and facilitate inclusion through increased connectivity and digital literacy. Open data can be used to solve these challenges and also as a way to include voices from communities that may not be prominent in current communities of practice around data science.

Why humanizing government data matters

Steven Goldsmith, the former mayor of Indianapolis, recently recognized the challenges presented by a lack of inclusion and representation in data science and the civic technology field. In his recent article in Governing, Goldsmith observed that “data dashboards, Web-based tools and mobile apps are typically built by relatively homogenous teams of developers for audiences that tend to share similar, relatively affluent demographic characteristics.”

As a result, many of the technological solutions developed with good intentions have had limited impact upon or relevance to problems of the communities that are not part of the discussion, in turn hindering their ability to help those who they intended to inform and empower.

This dynamic also ties into broader themes we keep hearing — as I noted in a post after the 21st Century Neighborhoods Symposium — that open data needs to be “humanized” by including residents in collection, analysis, use, and reuse.

Part of the process of humanizing data is ensuring that marginalized populations have a say in when and how data is collected, and when and where public policy decisions are made based upon it.

For example, more people of color can and should be represented in places like city data offices and other venues where data plays a significant role in government. These offices do important work and their staff bring unique, individual perspectives to that work. More of those perspectives should be from people of color, as well as other underrepresented populations. And, perhaps, their presence can help to identify and address any inherent machine bias that might exist in datasets, the algorithms they are based on, or the criminal justice system that uses them to make decisions.

How open data-driven projects can help

I discussed this issue at the CityCampNC unconference last month in North Carolina, where I proposed a panel entitled “How to make our movement more inclusive.” To my delight, it got enough votes to become an official session and was well-attended.

Our session explored both the scale and variety of inclusivity challenges. City staff who participated detailed their struggles with elevating issues of inclusivity in discussions with city leaders. Other participants spoke about the information and technical needs for community service organizations and marginalized communities, along with a disconnect that some feel exists between the civic hacking/data community and marginalized populations.

We discussed some potential approaches to improving upon this dynamic during our session. For example, Eric Jackson, the leader of Code for Asheville, shared that their group stopped having regular meetings and instead joined the meetings of other community organizations to learn about their data and technical needs and figure out ways to help. He said that this has helped the Brigade develop responses that were more responsive to the needs of the community of Asheville. Eric emphasized that personal engagement by people in data science with other community stakeholders can lead to better outcomes.

One example of a project which reflects this approach is OpenDataPolicing.com, a site which aggregates and presents open data about police stops, including demographic differences. The website was inspired by recommendations from President Barack Obama’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing, which encouraged local law enforcement to “embrace a culture of transparency”.

OpenDataPolicing.com was built by a partnership between the Southern Coalition for Social Justice, a local non-profit, and the Caktus Group, a Durham-based web development company. The project has helped catalyze reforms in North Carolina and other states. The website is now integrated into management protocols for Fayetteville, North Carolina, and is regularly reviewed by the city’s police. Since its launch in 2015, there has been a decrease in the “number of searches and use of force at stops” in Fayetteville.

Code for Asheville is now working with Code for Greensboro on a website that aggregates data on re-entry services for formerly incarcerated individuals in one place.

All of these projects rely on open government data from cities, a common trait that I am looking forward to discussing at Data for Black Lives.

Where tactical data engagement applies

Sunlight’s Tactical Data Engagement framework is our approach to this challenge of including more excluded voices. We outline ways to go beyond making public data accessible, by giving government officials tools to proactively work with distinct community groups to meet their information needs.

Creating “concrete and measurable change in the lives of black people,” as the Data for Black Lives project aims to do, is one of the most important ways TDE could be used.

Broader issues of digital inclusion create structural hurdles: communities of color are underrepresented in the data and tech communities that most often engage with city open data efforts. But this is no excuse for an “if you build it they will come” mentality that produces a de facto exclusion of vulnerable populations that have the most at stake in city decision making.

There are concrete steps that people who work on and with open data should take to build inclusivity into the process, and in so doing create more impact with open data.

Understanding the information needs of minority communities and advocating for cities – and governments at all levels – to open data in ways that are safe, ethical and useful to those communities is essential to that goal.

Open data from city governments plays an important part in informing conversations about racial justice, which in turn supports justice for all. I’m looking forward to having those discussions this weekend and in the work yet to come.