California, Florida Leading the Way to Local Government Fiscal Transparency

This guest post was contributed by Marc Joffe, a Senior Policy Analyst at the Reason Foundation.

In May, the California State Senate passed SB 598, the Open Financial Statements Act. The vote was an important milestone on the way toward opening up state and local government audited financial statements to more thorough analysis and comparison, but transparency advocates working in this space still have a long way to go.

About a third of the nation’s state and local governments produce audited financial statements, documents that provide actual government-wide revenues, expenditures, and debt levels verified by an independent public accounting firm. This contrasts with budgets, which, as forward-looking documents, only offer projected spending amounts rather than audited actuals.

Unlike budgets, audited financial statements also show the present value of a government’s pension and retiree healthcare liabilities – important components of a public sector entity’s financial health. They include financial statement footnotes that often reveal issues, such as pending litigation or loan defaults, not easily found elsewhere. The audited financials are often packaged together with information on the federal grants received by the government, including an independent auditor’s assessment of how the grant funds are being managed.

While it’s clear audited financial statements contain a lot of useful information, they have been challenging to gather and analyze. When the federal government began collecting state and local government financial audits in the 1980s, documents were provided as hard copies. Starting in the late 1990s, some entities began publishing financial statements on their web sites. This transparency innovation became more widespread after the Government Finance Officers Association (GFOA) issued a best practice document recommending web site posting of audits and other financial disclosures.

More recent developments have continued the trend toward greater availability of audited financials. In 2008, the Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board launched the EMMA system which provides online access to audited financial statements submitted by municipal borrowers. Unfortunately, EMMA’s Terms of Use forbid crawling the site, effectively preventing bulk collection of these disclosures.

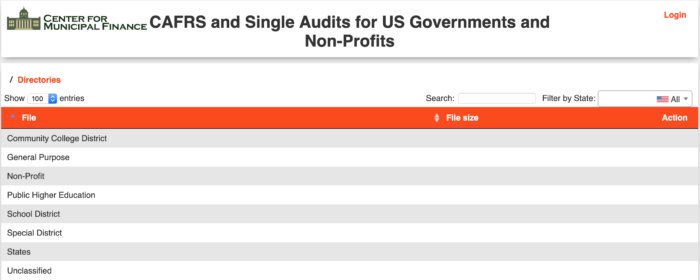

Over the last twenty years it has become much easier to obtain state and local audits, but we still lack a comprehensive, free repository of these documents. With a grant from Microsoft, I have started creating such a library at http://cafrs.municipalfinance.org but this remains a work in progress.

Audit Data Locked in PDFs

Although barriers to document access have been lowered, extracting data from audited financial statements remains a serious challenge. These documents are published as PDFs, and in many cases, they are scanned and/or secured, hampering the use of text and table extraction software. This limits the utility of the data, and the ability for it to be repurposed.

To its credit, the federal government has begun to require that PDFs submitted with Single Audits are unencrypted, unlocked and contain at least 85% searchable text. State and local governments that upload audits to the Census’ Harvester system must use an online validator that enforces these restrictions.

While searchable, unlocked PDFs are an improvement, a far better alternative is to migrate audited financial statements to a machine-readable format. This transition occurred many years ago for corporate financial reports in the US and for municipal disclosures in Spain.

Both the Spanish government and the US Securities and Exchange Commission embraced eXtensible Business Reporting Language (XBRL), which is an application of XML to financial reporting. Applying XBRL to a new category of financial statements – such as those published by state and local governments – requires the development of a taxonomy, a standard vocabulary of terms that can be used to tag financial statement items. Proper use of a taxonomy ensures comparability across financial statements. Taxonomies can also include validations which allow filings to be checked for internal consistency before being posted on the internet.

In 2008, the Association of Government Accountants published a study describing an application of XBRL to the State of Oregon’s Comprehensive Annual Financial Report (CAFR). For the study, they developed a simple taxonomy covering two of the state’s accounting schedules. Unfortunately, nothing much happened after the AGA study was published, perhaps because government finance officers had to deal with the Great Recession. More recently, support for machine-readable CAFRs has re-emerged.

In 2014, the Sunlight Foundation sent an open letter to the Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board advocating this idea. It was also effectively (but not explicitly) included in the Financial Transparency Act (FTA) of 2015, which would have required MSRB to adopt machine-readable formats for a wide variety of disclosures. More recently, the Grant Reporting Efficiency and Agreements Transparency (GREAT) Act of 2019 (H.R. 150) also implicitly includes this reform. Neither the FTA nor the GREAT Act have become law, but the GREAT Act passed the House earlier this year and is now advancing in the Senate.

Progress in States

In the absence of conclusive national action, transparency advocates have turned their attention to states. In 2018, the Florida legislature passed HB 1073, which, among other things, empowered the state’s Chief Financial Officer to develop an XBRL taxonomy with an eye toward adopting the standard in 2022.

The new California bill, which goes to the State Assembly this summer and has support from State Treasurer Fiona Ma, would create a nine-member commission to study the concept, potentially develop a taxonomy and make a recommendation to the state legislature regarding further actions. A California taxonomy could borrow from a prototype being developed by the standards organization, XBRL US.

Meanwhile, advocates are having conversations with officials in other states about possible legislation or pilots implemented by executive agencies. If you’d like to support machine-readable financial reporting in your state, please get in touch!

The Long Road Ahead

Increasing public employee retirement costs and the need to update crumbling public infrastructure are heightening interest in state and local finance. Researchers, municipal bond investors and active citizens all have questions about whether their state, city, school district or special district can shoulder the demands being placed upon it.

Big data can help answer these questions; opaque PDFs scattered around the web cannot. Instead, the US should have a free, open repository of audited state and local financial data, just as we already have such a repository for corporate financial data. At a time of Congressional gridlock, the best way to advance this vision appears to be through state legislation and private initiatives.