Ownership, evictions, and violations: an overview of housing data use cases

Cities from coast to coast are grappling with major challenges in providing safe and adequate housing for their residents, as developers continue to build in luxury condominiums and affordable options dwindle.

In the face of this struggle, civic hackers and housing advocates use open data to collaborate to develop tools to protect renters’ rights and aid communities facing displacement. My project aims to build a tool that helps hackers collect and organize housing data that is readily available.

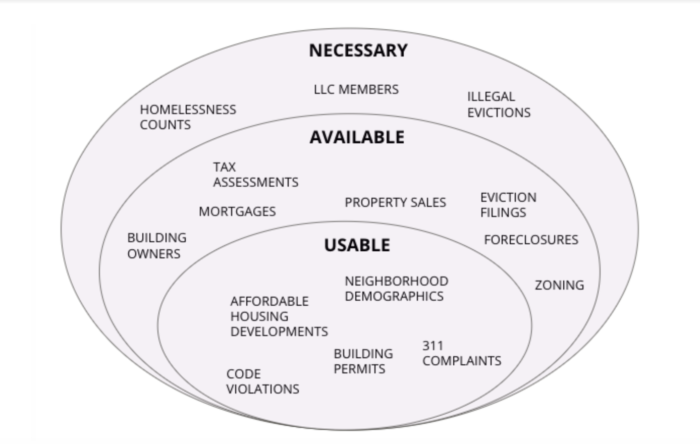

However, open data on housing is not always readily available or easy to work with. And the variety of unique housing-related issues necessitates many different types of data to address. Some necessary data may be unavailable, requiring significant effort to actively collect or advocate for the release of it. Other data, while perhaps readily available, might require an arduous process of scraping, cleaning, and record-linkage to make usable.

Figure 1: The necessity, availability, and usability of housing data varies across cities. This is an example of how the landscape of housing data might look for a single city.

All of the housing-related data shown above are important, in one way or another, for building thriving cities where residents have equitable access to housing. Cities facing similar housing issues can learn from each other to better understand how the necessary data can be collected and made usable to benefit residents. Here, I focus on the following three types of housing-related data, their relative degrees of openness and usability, and illustrate more use cases from cities where civic hackers and housing advocates have collaborated.

- The real estate industry seeks to keep deeds & ownership data private, but hackers and advocates can play a role in identifying building owners for tenants

- Evictions data often isn’t collected or examined, groups throughout the country working to change that

- Building permits, complaints, and violations are commonly available on open data portals. I explore some examples of how this data has been used.

Deeds & Ownership

Housing advocates often need to answer questions such as “Who are the top evictors in a neighborhood?” and “Which owners are neglecting building maintenance responsibilities?” Property owners are able to shield themselves from this accountability by purchasing property through Limited Liability Corporations (LLCs), thereby obscuring the connection between their personal identities and their buildings. Lawmakers at both federal and local levels have introduced legislation to shed light on LLC owners’ identities with limited success.

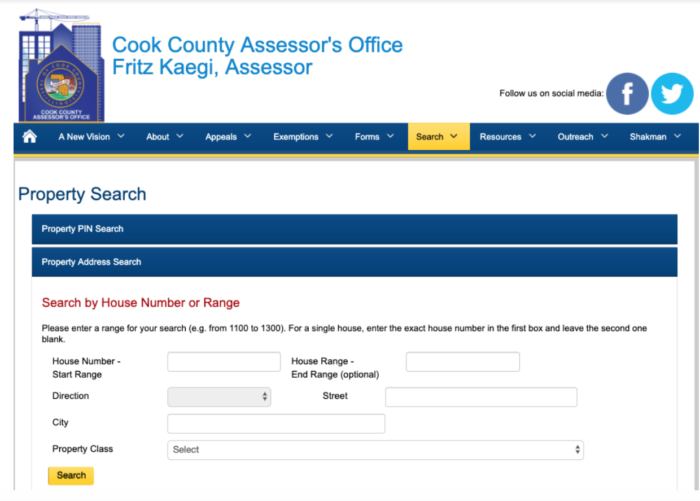

Depending on the municipality, LLCs can be identified via address search on county assessor or recorder of deeds’ websites. However, to obtain data in a machine-readable format for analysis, there is little recourse beyond web scraping, or submitting Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests. Even then, identifying LLCs’ members may not be possible depending on whether the city has a policy in place to collect such data, and if it has usable fields for record linkage.

Where civic hackers have managed to obtain and analyze ownership data, tenants and advocates have had more opportunities to uncover patterns of abuse and hold landlords accountable. For example, hackers at the Housing Data Coalition developed a publicly accessible app based on a database which draws from multiple government sources and links records to give residents information property ownership and shell company networks in their neighborhoods. By knowing who owns what, city officials and tenants have the power to understand patterns of behavior and hold property owners accountable.

Evictions

While eviction rates are an essential indicator of economic well-being within cities, there is no single nationwide database that tracks evictions. Matthew Desmond’s Eviction Lab out of Princeton University, popularized by the Pulitzer Prize-winning book entitled Evicted, is an existing effort to create such a database. On the local level, very few cities release eviction filings data, and even with such data, a significant amount of technical effort is required to match records and generate metrics. This is not without good reason, as such openness violates tenant privacy protections and can be used by the real-estate industry against tenants’ interests.

The Bay Area-based Anti-Eviction Mapping project has sought to collect and analyze this data through requests to county boards, rent boards, and surveys from community partnerships. In doing so, they have highlighted important trends such as the relationship between Airbnb listings and evictions, the consequences of owner move-in evictions, and many more.

In a similar vein, partnerships in Milwaukee between the City Attorney’s office and local organizations has created a database of evictions records that serves to better inform how landlords are investigated for violations and where outreach to tenants is needed. The work being done in the Bay Area and Milwaukee exemplifies an opportunity for local researchers, hackers, and advocates to share data in a manner that protects tenant privacy while exposing local drivers of evictions and recommending evidence-based policy responses.

Building Permits, 311 Complaints, Building Violations

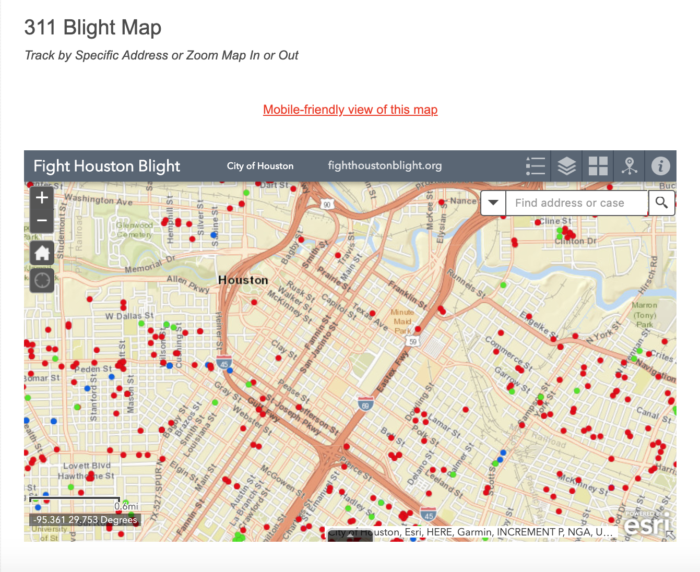

Among the more commonly available datasets on cities’ open data portals are building permits, building violations, and 311 complaints. In building housing apps for advocates, civic hackers are often able to obtain this data as “low hanging fruit”.

Up-zoning has gained nationwide attention as a potential supply-side solution to the housing shortage, and data on building permits plays an essential complementary role with zoning data in understanding how the housing supply is changing. An analysis of building permits in Washington D.C. found that wealthy neighborhoods were not seeing their fair share of new housing, driving gentrification into middle and lower-income areas.

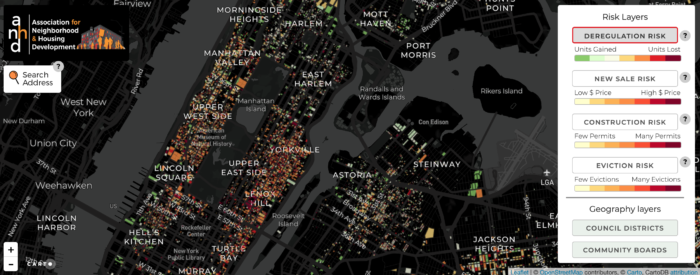

In addition, building permits can be an important indicator of planned renovations that will destabilize the affordability of rental units for tenants. New York City’s Displacement Alert Project specifically tracks categories of building permits that may indicate upcoming rent increases to alert neighborhood activists.

Information on building violations as a result of inspections and building-related 311 complaints are similarly tracked in the Displacement Alert Project. Even without linkage to ownership data, tenants and advocates are able to understand landlord negligence at a building level, answering questions such as “What types of violations occur in my building?” and “Does my building’s permit activity suggest risk of a new sale?”

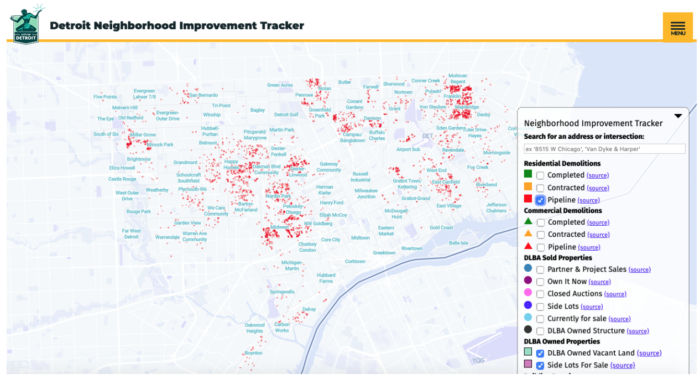

Beyond serving housing advocates, civic hackers have an opportunity to use this data to directly support city government’s operations. In Detroit, local hackers developed a Neighborhood Improvement Tracker, which uses building permit data in conjunction with building demolitions and property sales through Detroit Land Bank. The city has adopted this tool to bring transparency to publicly funded efforts to demolish buildings and reduce blight.

The examples described here only scratch the surface with regards to how civic hackers can use housing data to support advocates and inform local policies. The preservation of affordable housing is another issue that can benefit immensely from partnerships between hackers and advocates. And zoning data’s complexity and uses merits an article of its own. The fact that the real-estate industry has significant incentive to keep its data proprietary and invests heavily in market analytics to maximize profit makes these partnerships even more essential as cities continue to grapple with the many multidimensional issues related to housing.