Data is changing our approach to prisons (and saving us money, too)

Earlier this year, former Attorney General Eric Holder addressed a crowd of conservatives and liberals that included both representatives from Koch Industries and the American Civil Liberties Union. The unlikely pairing was symbolic of the Bipartisan Summit on Criminal Justice Reform’s unique appeal within an otherwise divided political landscape. In the past, leaders of both parties have tripped over each other to project a “tough on crime” persona, which led to policy outcomes that effectively accelerated the scourge of mass incarceration.

That attitude towards crime prevention has shifted dramatically since. Just this week, the White House — on the heels of releasing the final report of the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing — announced a cooperative effort supported by the Sunlight Foundation to improve open data policies in local police departments so that citizens can keep tabs on their performance. During his summit speech, Holder similarly advocated for evidence-based strategies “to ensure that 21st-century challenges are met with 21st-century solutions,” referencing the Department of Justice’s Justice Reinvestment Initiative (JRI).

This federal-level initiative is centered around encouraging state and local governments to apply concepts that criminologists have long been proving are effective, like risk assessment tools and treatment programs. The program, which supplies state and local governments with relatively inexpensive technical assistance to enact and evaluate criminal justice reform policies, helps governments achieve massive cost savings, as well as lower incarceration and crime rates. Eventually, the goal is to spread the idea nationally, and it’s working — sentencing and corrections reforms have been hugely successful in winning over bipartisan support from lawmakers around the country.

The true value of the initiative is hard to quantify. Evidence-based practices — the phrase du jour in criminal justice circles — is what the initiative promotes, and the policy analysis that it helps finance allows jurisdictions to better assess the impact of reforms they put into place. Cost savings calculations are a prickly business because of the scale of the criminal justice system and the multicausal nature of its outcomes, but they give advocates for reform a platform to stand on in front of a legislature that ultimately has the final word.

Furthermore, cost savings only encompass the most tangible results produced by reforms. The other component of the initiative is ingrained in its title: reinvestment. Savings achieved by improving processes and protocols within the criminal justice system are then repurposed to continue developing programs that may have previously lacked proper funding.

A prime example of the initiative’s success is South Carolina, where the state’s Sentencing Reform Commission noted in a 2010 report to the legislature that a major driving force in the soaring correctional population was an increasing number of offenders who were being reincarcerated for technical violations while on probation or parole. A looming increase in annual operating costs and the need for new prison space construction to house a growing number of offenders prompted the assembly to overwhelmingly pass a wide-reaching crime bill called the Omnibus Crime Reduction and Sentencing Reform Act that same year, which, among other changes, provided a system of performance incentive funding. The bill allowed for resources to be shifted from prisons to probation and parole.

The Justice Reinvestment Initiative was pivotal in tracking the money saved by reductions in returns to prison and new felony offense convictions of those on parole or probation. Technical assistance funded by the JRI helped state agencies develop a methodology for calculating state expenditure savings on an annual basis, which totaled over $5.25 million in fiscal year 2013. Because the act allows for the committee to recommend appropriating up to 35 percent of cost savings toward further sentencing reform, almost $2 million was set aside for caseload management, SMART Probation and victim support initiatives — programs key to the state’s efforts in reducing criminal recidivism and improving public safety.

In 2011, Georgia was facing similarly poor returns on investment in the criminal justice system. Over the last two decades, both the state’s incarcerated population and its spending on corrections had doubled, while its criminal recidivism rate remained decidedly unchanged. With technical assistance funded through the Justice Reinvestment Initiative, the state’s legislature established a Special Council on Criminal Justice Reform to scrutinize sentencing and corrections data, gather input from stakeholders and examine state policies and practices. The broad range of data-driven reforms proposed by the council were signed into law in 2012, otherwise averting cost increases of $264 million associated with a projected 8 percent growth in the correctional population over the next five years.

By capping sentences in probation detention centers, expanding access to residential substance abuse treatment programs and mandating electronic records submission, the Georgia Department of Corrections has reduced payouts to counties and freed up thousands of jail beds that are now used for transitional programs to further the department’s goal of successful offender re-entry. Cost savings have also allowed the state to reinvest almost $40 million over two years into expanding accountability courts and strengthening offender supervision.

The initiative is centered around making policy changes not only cost-effective but also sustainable. Funding is focusing on implementing programs with fidelity, which involves ensuring staff — like parole officers who regularly interact with offenders — are trained properly, recorded during sessions, coached and given feedback that ensures they meet performance criteria set by program models. That standard also extends to the technical aspects of implementation, like validating risk assessments locally so that programs can be properly targeted to those that need them the most.

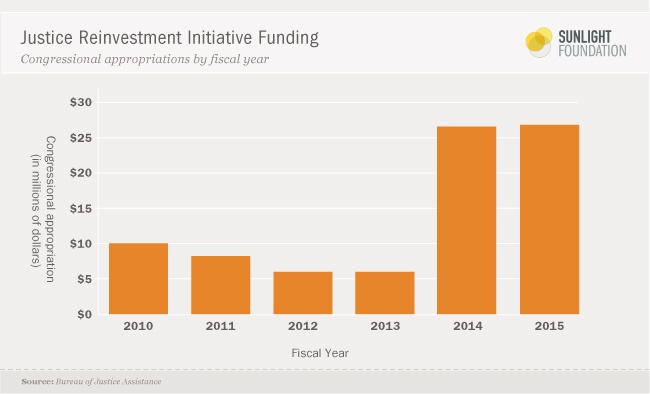

In 2014, the Bureau of Justice Assistance began phasing in direct grants for participants of the initiative, paving the way for states to take the lead on implementing criminal justice reform. These grants give states who have gone through the process of adopting the initiative the opportunity to build on their progress. Delaware, for example, requested $1.75 million for validating its pretrial risk instrument, funding more supervision officers and providing services for low-risk pretrial populations. By supporting states who have already cleared the hurdle of adopting the initiative’s provisions with fidelity, its proponents hope to spur lasting change that will become the paradigm for states continuing to struggle with the complexities of criminal justice in the 21st Century.