How political megadonors can give almost $500,000 with a single check

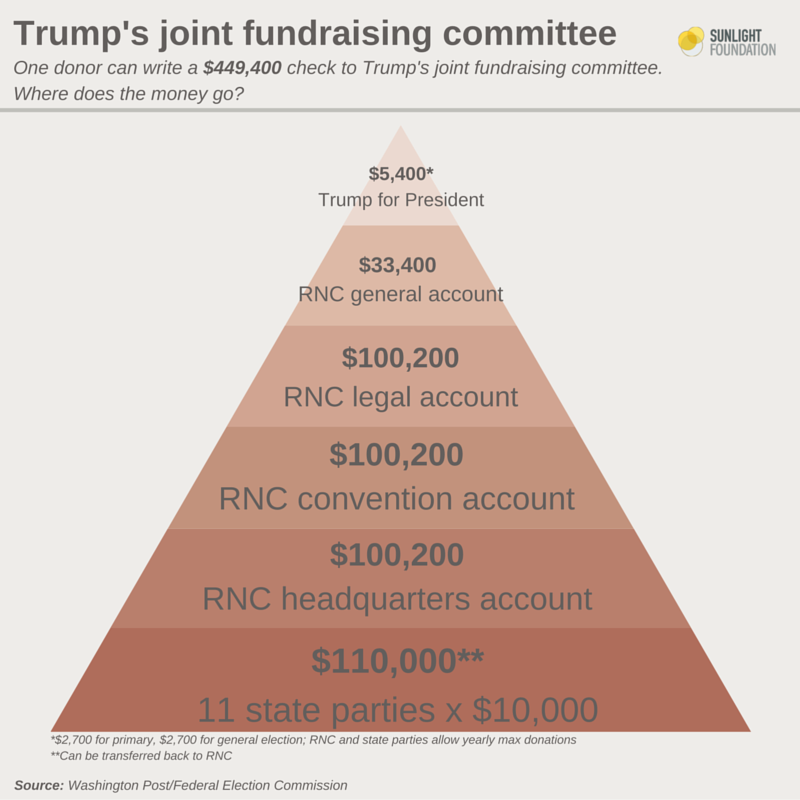

On May 17, Donald Trump announced an arrangement with the Republican National Committee (RNC) that will allow individuals to donate almost $500,000 each to a joint fundraising committee between Trump, the RNC and 11 state Republican parties. In 2012, Mitt Romney’s joint fundraising committee could only raise $135,000 from each individual. What happened in the last four years to make these numbers so much higher?

A couple of developments got us here. First, in 2014, the Supreme Court issued a ruling in McCutcheon v. FEC that eliminated aggregate limits on donations. Before McCutcheon, an individual could donate a maximum of $123,000 to political candidates, PACs and parties in a single cycle. After McCutcheon, although contribution limits to each committee still apply, donors can give as much as they want overall. While they are still limited in how much they can give to each candidate and committee — a maximum of $2,700 to a campaign per election, $5,000 per year to a PAC, $33,400 per year to a national party committee, and so on — they can now give the maximum amounts to as many candidates and PACs as they want (if they have the cash and the inclination). That allows wealthy donors to give huge amounts overall.

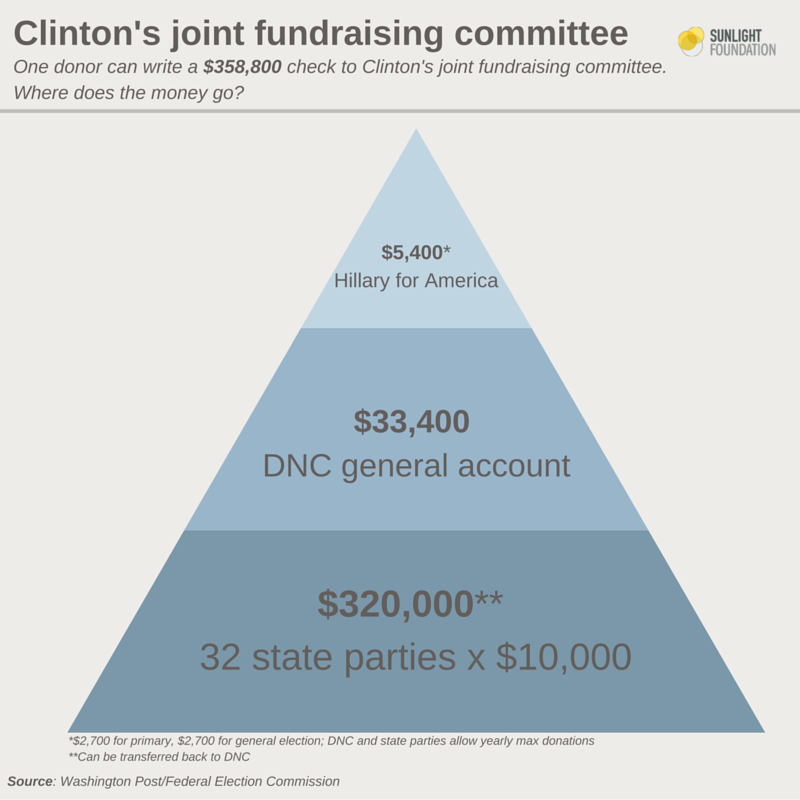

In the majority opinion in McCutcheon, Justice Samuel Alito dismissed concerns that joint fundraising committees would be used to solicit massive checks for individual candidates as “wild hypotheticals.” Almost exactly half the money given to the Clinton Victory Fund, a similarly structured fundraising vehicle for the Democratic frontrunner, has gone to Clinton — the other half has gone to the Democratic National Committee and state parties. (However, almost all the money transferred to state parties has been transferred directly back to the DNC.) We don’t know how the DNC will spend that money — whether it will be spent to elect Clinton or on state and local races. It’s likely to be both. (It’s important to note that Clinton’s campaign still cannot accept more than the max $2,700 per election into her campaign coffers.)

But what we do know is that the national Democratic party retains control over how those funds are spent, rather than leaving it up to the state parties. This allows both parties to circumvent of contribution limits: Individuals aren’t supposed to be able to give more than $33,400 to the DNC (or RNC) per year, but when contributions to state parties are routed straight to the DNC, it effectively allows people to give much, much more to the national party.

Second, also in 2014, a rider attached to the omnibus appropriations bill (the bill that funds the federal government) dramatically raised the contribution limits to party committees by allowing them to establish separate accounts for conventions, building costs (the party headquarters) and legal fees. Each of these three additional funds can accept $110,000 per year from individuals. This raised “the cap on an individual’s total contributions to all national political party committees from $97,200 per year to $777,600 per year.” The growth of outside money after Citizens United had left parties feeling cash-strapped, and some had speculated that allowing parties to raise more money would “pry back some power and control from outside groups.” Whether or not parties have more control now, outside spending is continuing to grow.

Trump’s new joint fundraising committee with the RNC, Trump Victory, takes advantage of these rules. Matea Gold at The Washington Post did the math:

Unlike the Hillary Victory Fund, Trump Victory includes the three additional accounts at the RNC that can accept much more money; the DNC has their own program for soliciting donations to those accounts, which explains why the contribution limit for Trump Victory ($449,400) is so much higher than the limit for the Hillary Victory Fund ($358,800).

Donations to the “new accounts” are only supposed to be spent on what the account is intended for (building costs, legal fees or conventions), but Paul Ryan of the Campaign Legal Center says these accounts can amount to “slush funds” for the parties, as he told the Center for Public Integrity:

The parties will do what they always do, which is use these new accounts as slush funds to pay for anything they feel like paying for that they can possibly get away with arguing falls within the meager constraints of the plain language of the statute.

This election cycle, between the Hillary Victory Fund and the DNC’s donor package, a donor can give the DNC and Clinton $1.1 million; between Trump Victory and the RNC, a donor can give the RNC and Trump $783,400.

Astute readers will note that the DNC’s arrangements (the Hillary Victory Fund plus the DNC donor packages) allow it to accept more money than the RNC’s (Trump Victory plus RNC donor packages). That’s because the DNC’s agreement includes more state parties than the RNC’s, 32 versus 11. It’s not immediately clear why the RNC deal includes fewer states, but these agreements with the states have to be hammered out, and that isn’t always smooth sailing — see the controversy and reported dissent among state parties over the flow of cash from the Hillary Victory Fund to state parties and straight back to the DNC.

Trump Victory and the Hillary Victory Fund aren’t the only joint fundraising committees, of course. Team Ryan, which includes Speaker of the House Paul Ryan, R-Wis., his leadership PAC, Prosperity Action Inc., and the National Republican Congressional Committee (NRCC), has raised more than $22 million; $12 million of that has gone to the NRCC. Priorities USA, the largest super PAC supporting Hillary Clinton, has a joint fundraising committee with EMILY’s List; it’s raised $750,000 from just two donors, the American Federation of Teachers and Amy Fowler, a New York philanthropist and author of several books on gardening.

While we have never seen joint fundraising committees raise this much money, the vehicles themselves are not new to this cycle. Romney and Obama both utilized these committees in 2012 and in 2014 (post-McCutcheon decision) Sunlight research showed more than 200 active joint fundraising committees.

As we enter the most expensive presidential election in history, with $1 billion spent already and some estimating the entire election will cost $5 billion, these high-dollar donors are vital to the parties. Almost half the money donated this cycle to super PACs as of February came from just 50 families, and in 2014 only 135 people gave more than $500,000 to super PACs. Clearly, the number of people with such huge political spending power who can contribute these vast amounts is limited — and the priorities of the super-rich don’t necessarily reflect the priorities of the public at large.

Thanks to McCutcheon and the end of aggregate contribution limits, deep-pocketed megadonors are more valuable than they’ve ever been.