How Much Did Money Really Matter in 2012?

This post was prepared in collaboration with Alexander Furnas, Amy Cesal and Alex Engler

One of the emerging post-campaign narratives is that all the outside money (more than $1.3 billion) that poured into the 2012 election didn’t buy much in the way of victories. And as we dig through the results in detail (our extensive data visualizations and analysis are below), the story holds up: we can find no statistically observable relationship between the outside spending and the likelihood of victory.

Looking closely at the data helps to clarify and explore this emerging narrative in numerous ways. It also helps us to see some other smaller effects of money. It appears that candidate spending may have mattered a bit more than outside spending, especially for Democrats. It also appears that outside spending may have contributed slightly to the vote share, though not to the probability of victory.

This post is based on House results, both because looking at the House gives us a larger sample size, and because there’s more of a likelihood that money could make a difference in House races, given the smaller size of House seats (compared to the Senate), the recent redistricting and the fact that we’ve had three House elections in a row with high turnover.

Spending in general

First an overview. As of September 6, two months before the election, the Cook Political Report listed 90 House seats as either likely for one party, lean for one party, or toss-ups. These were the seats where money could make a difference if it were to make one. (Before we proceed, a few caveats: 1. The candidate spending totals are through October 17; and 2. For purposes of the analysis we include outcomes still pending final approval.)

Outside spending on these 90 seats was just over a quarter of a billion: $250,656,656, and candidate spending was just short of $300 million: $297,947,7717. In the 25 toss-up races, candidates spent $100,164,189; outside groups spent $140,043,821.

The table below provides an overview of the spending by Cook category. One takeaway is that Democrats actually kept pretty solid pace with Republicans on the toss-up races, but Republicans outpaced Democrats in outside spending in Likely D seats.

Outside Spending

(For a detailed overview of outside spending in the House, click here)

(For raw data on House races, click here)

Our first visualization looks at the outside spending by race. We’ve broken down the races by their Cook Report rating as of two months before the election, and arrayed them by the Republican spending advantage. The bigger the bubble, the more total spending in the race. Red seats were won by Republicans, blue seats by Democrats.

Republicans did win the toss-up with the biggest Republican outside spending advantage (PA-12). But Democrats won the next four races with the biggest Republican outside spending advantages (CA-52, MA-6, NC-7 and IL-11). In addition, the one “Lean Republican” seat with the greatest Republican outside money advantage, GA-12, also was won by a Democrat. It is possible that the high levels of Republican outside money spending in these races signaled weakness and a need to catch up. Whether or not this is true, the money generally did not have the desired impact.

More outside money went to help Republicans in 60 of the 90 races we looked at, including 14 of the 25 toss-up races. Yet, only nine of the 25 toss-up seats went to the candidate with more outside spending, and just four of the 12 races with an imbalance of $1 million or more went to the candidate with the outside spending advantage.

| Spending Imbalance | races | winners |

| R advantage | 14 | 3 |

| D advantage | 11 | 6 |

| >$1M difference | 12 | 4 |

| $500K-$1M difference | 6 | 3 |

| <$500K difference | 7 | 2 |

Republicans lost 11 of the 14 toss-up races where they got more outside spending than the Democrat. Democrats actually won 6 of the 11 races where they benefited, just barely over half.

(For the raw data behind these charts, click here)

Republican outside spending advantages did not have any noticeable effect on the Republican margin in the 25 toss-up races. The correlation between the two is -0.067, which means that there is no statistically meaningful relationship at all.

A regression analysis, which controls for a few other factors (reported at the end of this post) finds no impact of Republican total outside spending on the vote share, though it does find that each additional super PAC million spent on behalf of a Republican boosts the Republican vote share by 0.16 percentage points. This, however, did not seem to have any impact on the likelihood of a Republican victory in these seats.

The regression analysis also finds a slight effect for Democratic outside spending. Each additional million of outside spending on behalf of a Democratic candidate is associated with a reduction in the Republican advantage by one point. However, this result is just outside the traditional margins of statistical significance, so it should be taken with a grain of salt.

It’s also certainly possible to find cases where outside money appeared to make a difference, and we hope that the visualizations presented here will empower readers to explore what happened in particular races. But taking the election as a whole, the data suggest that outside money had little impact on outcomes.

Candidate Spending

Money seems to matter a little more when we just look at the candidate spending, particularly in the toss-up races. In 15 of the 25 toss-up races, the candidate who spent more won. And in the 17 races where one candidate outspent the other by at least $500,000, that candidate that did so won 11 of those races (65%). It’s not statistically significant, but still quite suggestive. (We also should reinforce that these candidate spending numbers are only current through October 17.)

(For the raw data behind these charts, click here)

In particular, the Democrats who spent more than their opponents seem to have done quite well. In 13 of the toss-up races, the Democratic candidate outspent the Republican candidate (as of our most recent data). Democrats won 10 of these races (77%). Republican candidates, meanwhile, only won five of the 12 races where they outspent the Democrat. So part of this effect could be simply that Democrats did well all around. Still, the fact that a spending advantage improved a Democrat’s chance of winning from 58% to 77% is suggestive. The regression results shown at the end of this post also provide some qualified evidence that Democratic candidate spending is associated with increased likelihood of a Democratic victory, though the impact is well outside of traditional boundaries of statistical significance.

| Spending Imbalance | races | winners |

| R advantage | 12 | 5 |

| D advantage | 13 | 10 |

| >$1M difference | 7 | 4 |

| $500K-1M difference | 10 | 7 |

| <$500K difference | 8 | 4 |

We can also see some relationship between candidate spending and vote share. Noticeably, in five of the eight toss-up races that Republicans won, they outspent their Democratic counterparts.

Dark Money

One of the biggest stories of this election season was the rise of dark money groups, which spent hundreds of millions of dollars. As we’ve documented, this money went to benefit Republicans by a 4-to-1 margin. (By dark money groups, we mean groups that do not disclose their donors and only have to disclose their spending in the weeks right before the election). If there’s a relationship here, it’s that more dark money is associated with losing candidates, especially among Republicans. Of the 25 Cook toss-up races we’ve looked at, the candidate backed by more dark money won only nine times.

In toss-up races where the Republican benefited from a dark money advantage, only five of the 18 seats went to the Republican. Democrats won four of the seven seats where they had the dark money edge.

(For the raw data behind these charts, click here)

Dark money spending

| Spending Imbalance | races | winners |

| R advantage | 18 | 5 |

| D advantage | 7 | 4 |

| >$1M difference | 5 | 2 |

| $500K-1M difference | 10 | 3 |

| <$500K difference | 10 | 4 |

The scatter plot below shows the relationship between the Republican dark money advantage and the Republican vote share. The correlation between Republican dark money spending and Republican vote margin is -0.04. The correlation between Republican dark money spending advantage and Republican vote margin is -0.06. Regression results (at the end of the post) show Democratic dark money associated with a lower Republican vote margin, but not in a statistically significant way.

What it means

The numbers confirm the emerging narrative. We can find no statistically observable relationship between the outside spending in House races and the likelihood of victory. Candidate spending may have had a small effect. There may be some relationship between outside spending and the voting shares, but not in a way that was big enough to affect seats.

Why did this happen? We can’t know for sure, but we can certainly speculate.

National factors were more important. In general, Democrats did better than Republicans in close House elections, winning 17 of the 25 toss-up seats. Perhaps some of this was simply momentum from Obama, or other external factors that gave Democratic candidates a boost across the country, and that these forces proved more important than all the spending.

Outside spending produced a backlash. Perhaps outside spending, much of it negative, actually turned voters off. There is some evidence that negative advertisements promote a backlash effect, which is why candidates often let outside groups do their negative ads for them. Perhaps voters saw through this and punished candidates who they felt were going negative with too much outside spending.

Money has diminishing marginal returns. At a certain point, voters stop listening to the endless stream of ads and phone calls and other attempts at persuasion. It may be the case that voters were so saturated that the additional money, especially the late-game outside money, had no impact for this reason.

Outside spending is more about offense. Perhaps the slightly negative relationship between outside spending and likelihood of victory, especially for Republicans, reflects that outside spending was geared more towards races where one side had less of a chance of victory, but hoped that the extra boost from outside spending could have made a difference.

Candidate spending matters more. Candidates know their district, and they are better equipped to run a campaign that reflects that. Outside money that can’t coordinate with campaigns is less likely to be attuned to unique features and cultures of particular district, and also must buy television ads at a higher rate than candidates, meaning the money doesn’t go as far. Or perhaps candidate spending may just be a proxy for the intensity of candidate support within the district, which is likely correlated with a candidate’s likelihood of victory (though difficult to measure).

Regardless of which of these explain the result, one should not conclude that just because it wasn’t determinative, money is therefore irrelevant. As long as candidates depend on private donations, and those donations primarily come from very wealthy individuals, policy outcomes are likely to be distorted. We may have entered an arms race era where additional spending has a declining marginal impact, but that doesn’t mean that either side is going to put down its guns any time soon. In fact, there is a good chance that outside groups may see this not as a lesson that outside spending didn’t work, but that they have to adjust their strategies and spend even more. While this election may point to certain limitations in outside spending, it is very unlikely that it points to the end of it.

Regression results

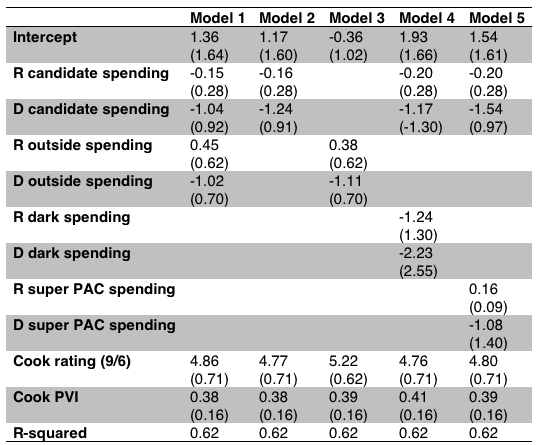

In order to statistically estimate the effect of different kinds of spending, we ran a few regressions. In the first set of models, our dependent variable was the outcome of the race, specifically whether the Republican won or lost. We modeled the likelihood of Republican victory as a function of different spending inputs, controlling for the Cook Report rating as of two months prior to the election (from -2 (Likely Dem) to +2 (Likely Republican), and the Cook Partisan Voter Index (PVI) to measure the district characteristics (the higher the number, the more Republican, in our model). We use a logistic regression to estimate the outcome:

Race outcome = a + ß1 Republican spending + ß 2 Democratic spending + ß 3 Cook Report rating + ß 4 District Partisan Voting Index

The results show no statistically significant effects of spending. But to the extent that there are non-significant effects, the effects for Democratic spending are greater than Republican spending – about twice as big for outside spending, ten times as large for candidate spending, and twenty times as large for dark money spending.

Results of Logit models:

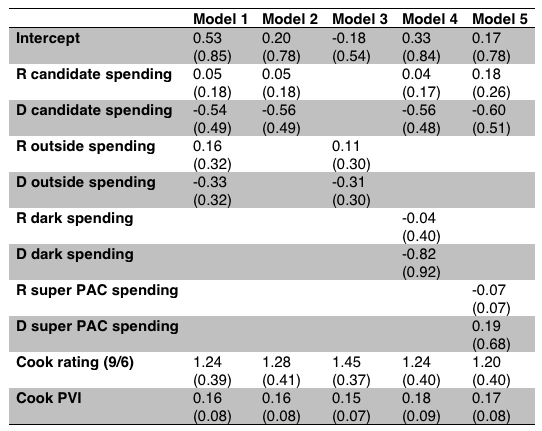

Another way to estimate the results is to see what effect the money had on the closeness of the race. Perhaps money didn’t impact the winning and losing, but the money shifted the vote share, or made the race closer than it would otherwise have been. Again, we estimate a the same basic model, but here our outcome variable changes to the Republican margin of victory, which ranges from -25 points (the biggest Democratic victory) to + 27.8 points (the biggest Republican victory)

Here we use an ordinary least squares linear regression, trying to explain the Republican vote share margin as a function of the same variables:

Republican vote share margin = a + ß1 Republican spending + ß 2 Democratic spending + ß 3 Cook Report rating + ß 4 District Partisan Voting Index

We get a few spending measures here just on the border of statistical significance. On average, Democratic outside spending seems to produce a one percentage point decline in the Republican vote margin for each $1 million in Democratic outside spending. Republican super PAC spending did seem to help Republican candidates, but only in a small way. Each additional Republican million in PAC spending is associated with a 0.16 percentage point increase in the Republican vote share margin. The results are interpretable as follows: The number associated with each spending variable represents what a million dollars in additional spending in each category is predicted to add to the projected Republican vote share margin in the race. The values in parentheses below represent the standard errors.

Results of OLS models: