The Landscape of Municipal Campaign Finance Data

Much of the time, campaign finance issues hold less of the public’s attention than budget questions, the posturing of candidates and elected officials, and political hot-button issues of the day. Who is funding candidates’ campaigns rises to the forefront only during election time — and even then, often only when there is a close race or a scandal. This sporadic attention can make it seem like an issue of fleeting importance, but providing public access to open campaign finance data remains a crucial accountability issue even when it is not election season. Knowing who helped pay for a politician to run for office can help reveal important narratives about political ties and whether actions taken in office might just be favors for donors.

Sunlight was founded, in part, to help address fundamental issues surrounding campaign finance at the federal level, advocating for more disclosure of this critical component of political accountability. With our new municipal focus, we were curious: What does local campaign finance disclosure look like? Transparency surrounding who is funding the campaigns of local city council members, mayors, and other elected officials is just as important as knowing who funded representatives in federal government. It helps the public see when a local government official might be swayed by a donor’s interest rather than answering to the community’s interests.

WHAT WE TALK ABOUT WHEN WE TALK ABOUT CAMPAIGN FINANCE DATA

When we talk about campaign finance data, we’re talking about any of the disclosures related to money received and spent on local campaigns. That means contributions, expenditures, committee information, and any other information required to be disclosed by municipal political actors.

For campaign finance data to be open, the public should be able to access and reuse information that is posted online and updated in a timely manner. This data should be published as structured data: making it searchable, sortable, and machine-readable (JSON, CSV, and XML are a few examples of formats that could be used). It’s critical that the default for the data be set to open, meaning that information from candidate’s campaign finance reports should be posted online proactively for anyone to view. Campaign finance data should be accompanied by relevant contextual information, like municipal regulations around campaign finance (citations of specific laws or ordinances are useful, along with descriptions of filing requirements), details about who regulates the matter at the local level, and any additional context, such as state laws that impact the issue. (State laws sometimes go so far as dictating local campaign finance transparency.)

So, how do cities measure up? Based on our research, there is a large gap between the highest and lowest levels of disclosure and openness, with some cities providing no information online and others releasing data in open formats. Many cities fall into a gray area somewhere in the middle, wielding web services in imperfect, but well-intentioned ways to share at least some of the data they collect. These variances help illuminate where improved disclosure is needed or would be useful.

BASIC ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF ACTIVITY

Some municipalities identify that campaign finance is being tracked at the local level, but do not provide any kind of disclosure of the completed forms or even fragments of the information contained in them. Sandpoint, ID, is one city that acknowledges campaign finance activity (by providing information about the code that regulates it), but it doesn’t seem to provide any online disclosure. Another basic method commonly seen at the local level is linking to a state portal that provides some information. Irvine, CA, for example, links out to the California Fair Political Practices Commission and the California Secretary of State, which has a variety of city and county campaign finance data. Jackson County, MO, links to the Missouri Ethics Commission page and notes several different layers of government offices where candidates for local office might report their campaign finance information. Linking to another source is a good step (and sometimes the only kind of practical disclosure, if a municipality doesn’t collect campaign finance data), but if a local government collects campaign finance data, that information should be easily findable on its website.

Other cities appear to be less clear about whether local campaign finance information can be found online and, if so, where it can be found. One campaign finance website for St. Louis City, MO links out to several state and local sites that might seem to have campaign finance reports but do not. The St. Louis Board of Election Commissioners has a website with a campaign disclosures page, but it, too, fails to actually provide much information around campaign finance. The campaign disclosures page is blank, and the search feature on the page doesn’t currently give the user any options for actually running a search. Navigating from the city’s main website to the “Elections and Voting” page doesn’t offer up information on campaign finance, either. This could be cleared up with a simple statement about whether the data is available online and, if so, where.

MINIMAL PROACTIVE DISCLOSURE

Going beyond the acknowledgement of local campaign finance reporting, some municipalities share filed information online — though not always in the most open formats. PDFs are one popular way for sharing campaign finance information online, though they are often far from the best option. Some PDFs are searchable (meaning search is possible through computer processing) because they are in a full text format, others have a mix of searchable text and un-searchable images, and others are totally in image format that cannot be searched at all. Most cities that do use PDFs to share campaign finance data have a mix of these (something often partly determined by whether a city allows for electronic filing, which we will explore further in this post).

Flagstaff, AZ, and Allentown, PA, are two examples of cities that link to many PDFs that are not searchable. The PDFs appear to be mostly scanned versions of partially-typed and partially hand-written documents, but the scanning means that the contents are in image format, which means there is no ability to search the actual campaign finance information. Colorado Springs, CO, and Austin, TX, have a mix of partially and fully searchable PDFs. The typed information on these documents (which includes form fields and sometimes what candidates have filled in) is searchable, but the most important information — the actual campaign finance data from candidates — is often handwritten and therefore not searchable. There are many more cities that could be listed alongside these examples.

Alexandria, VA, appears to be a unique example of how a variety of levels of searchability might be found in the release of campaign finance data. Some of the links on the campaign finance page lead to scanned versions of documents that are not searchable. There are also links to the Virginia State Board of Elections website for electronically filed reports. There, users can run a search for the local information and view the data in an online table. Users also have the option of downloading reports as fully-searchable PDF or XML files — formats that are far more open than any non-searchable documents on the city’s website. (This example also helps highlight the role states can play in how municipal campaign finance information is collected and shared.)

TAKING STEPS FORWARD

While PDFs can help, they are not a replacement for bulk access to campaign finance data. Some cities are taking a further step with campaign finance disclosure by providing a search function for sorting through the data. Doing this often means there is some level of structure and machine readability to the data, key qualities for making the information more accessible and reusable (not to mention usually making it more user-friendly).

Seattle’s campaign finance page, for instance, keeps data in static tables in some cases, but does provide options for sorting through the information. Users can run a search on the website for a list of information related to specific candidates, with the option of viewing the information online or downloading it as a CSV (an open format). Seattle also allows for searches of contributors or vendors. By providing these various ways to access the information, Seattle’s website caters to a large audience with a varying degree of knowledge about the data. It ensures that someone who wants to view all the data is just as accommodated as someone who wants to look at specific, narrow portions of it.

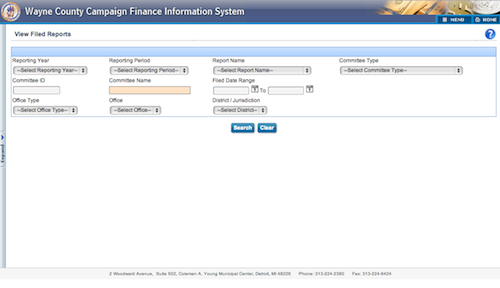

One common problem with more advanced city disclosure is the tendency to place data access behind a barrier of requiring search criteria. For example, Oakland County, MI, has a searchable website, but it is also one of several municipal websites that require search criteria for users to access any campaign finance information. By adding the option of browsing all the data, or even just bulk downloading all data, the website would enable a broader view of information in addition to the narrow scope returned by search criteria.

The variety of approaches for accessing and searching city campaign finance websites, not to mention the variety of ways information is returned from those searches, is expansive. All of the links on the Cincinnati, OH, campaign finance website lead to a searchable database, which returns a sortable page listing the election year, contributor, contribution amount, type of contribution (PAC, individual), and the candidate. The information is not downloadable, but at least it is searchable and sortable — important steps to empower users.

New York City and San Jose, CA, are two examples of cities that do provide search functions in addition to providing (at least some) documents in open formats, allowing for browsing data, giving options for exporting all data, and seeming to generally embrace some key open data principles in their campaign finance disclosure. It appears more cities are starting to think about how they can provide better access to campaign finance data that can be easily analyzed and reused.

E-FILING

Some cities require electronic filing of campaign finance reports, also known as e-filing, which is an important step to facilitate the production of electronic information that can be easily shared, processed, searched, and sorted from the onset of the report’s filing and the data’s creation. Allowing candidates for office to file their campaign finance information in a machine-readable format means it is easier to share the data in that format, too.

Some of the benefits of encouraging e-filing are reflected in the Wayne County, MI, campaign finance website. E-filing is required in Wayne County for committees spending or receiving more than $20,000 in a certain period, and it is strongly urged for others. Database searches, which are unfortunately required for viewing info, return a table of results with the option for downloading a PDF version of each report. If the PDF available for download is not searchable, there is a note next to it labeling it as a “Paper” report. All of the reports without this flag are fully searchable PDFs — a product of the cities’ e-filing system. Wayne County’s overall campaign finance system could still be better, of course, by not requiring searches to view information and by requiring e-filing so all reports are fully searchable. Meanwhile, the functions that are available on the website show the potential for better access empowered by e-filing.

There are plenty of examples of municipalities that do have e-filing but don’t have open data, however. Virginia Beach, VA, has e-filing and allows for a search of the reports, but the searches lead to static tables on web pages. Taking this approach misses out on the full potential of electronically filed information: rather than being able to view only very specific data one page at a time, this information could also be put into a searchable, sortable table, made available for bulk download in an open format, and be improved in other related ways for users.

***

Very few cities actually meet all of the essential disclosure practices for open campaign finance data. There are many cities not discussed here that fall into additional gray areas; they might provide search options for browsing information, for example, but not provide the results in open formats; they might have e-filing but not provide ways to search the information; or they might have some other combination of meeting certain criteria but not others. (For that matter, there are also more cities that have very low or high levels of disclosure and use of open data.)

There are many more issues related to campaign finance, of course, that are crucial to helping complete the vision for transparency around this set of information, such as understanding the impact of “dark money,” or the money flowing into campaigns that does not have to be disclosed. We track these issues closely at the federal level and have many peer organizations keeping their eyes on the subject. We’ve compiled links to some of these resources in our research. In upcoming posts, we’ll not only continue to unpack how and why municipal campaign finance data should be improved, but we’ll also dig into some of these overlapping issues, such as financial disclosures and conflict of interest statements. We would love your input as we continue to look at campaign finance data and related issues.