The Impact of Opening Up Municipal Campaign Finance Data

What kinds of information municipalities release about campaign finance and how they release it varies widely, but the impacts that come from its release are fairly universal. Every year, as elections take place in municipalities of all sizes across the country, journalists and other watchdogs track campaign finance data to follow the trail of money in politics and contextualize this information for the public. Sometimes, the narratives revealed in this process have led to reforms at the state and local level as people realize, and seek to curb, the influence that money can have on government officials’ decisions. Accessible campaign finance data paves the way for these activities and others, and its potential impact only continues to increase as more transparency and flexibility are built into the data releases.

NEWS STORIES

News stories are one of the most prevalent ways that campaign finance information gathered and released by the government is put to use. Journalists connect the details and often show how money might be impacting decisions being made by those in power. In Washington, D.C., for example, an investigation by the local radio station WAMU found that developers who contributed the most money to city council members’ campaigns received most of the subsidies for development. The series of stories prompted D.C. council members to push for legislation to help reform the system, citing the negative impact of the influence of money: It was with the disclosure of political money and its influence that change was prompted.

REFORM EFFORTS

D.C. is not the only locality working to reform campaign finance systems. Sometimes, the reform is sparked by seeing the need for increased access to this information in open formats. Oakland, CA, started requiring all local candidates and committees to electronically file their campaign finance reports earlier this year. The move came after, in 2012, candidates were allowed to e-file as part of a new online disclosure system, but those who continued to submit paper reports caused more work for city staff. The paper reports had to be scanned and posted online as PDFs, meaning they weren’t searchable. The reform requiring e-filing means all campaign finance information from candidates can soon be online in more open formats, empowering analysis, stories, and reuse of the data. (The trend toward open formats is visible at the state level in California, too.)

APPS

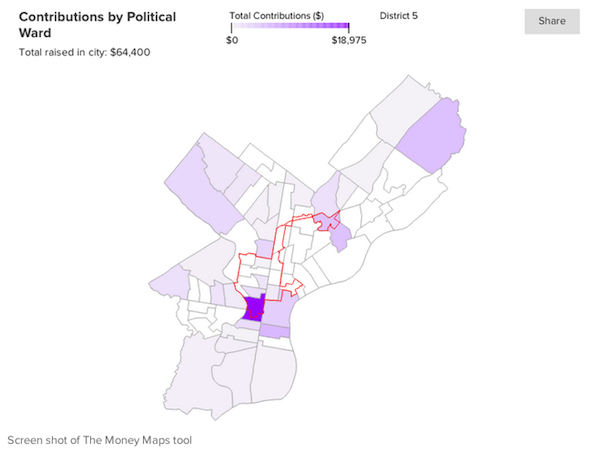

Beyond news stories, open campaign finance information also fuels apps that can make it easier for people to search through and make comparisons with the data. AxisPhilly, a Philadelphia non-profit news organization, created an interactive map showing where campaign contributions came from for specific members of the city council. Mapping out the data helped show that much of the money raised by council members did not come from within their respective districts. AxisPhilly reporters used the campaign finance data and their map to show changes over time in how much money flows into council campaigns and where the money comes from, leading to a rich narrative about political ties and influence.

These kinds of apps are so useful that The New York Times developed an API using Federal Election Commission data to help developers and journalists create apps that include “a snapshot of campaign finance data for a particular ZIP code.” The API provides updated campaign finance data from the FEC within minutes after it is filed, allowing the apps that use it to provide the most recent information to users. That means media and their readers have access to timely information about what interests are funding political campaigns in their area.

Local governments are finding ways to contextualize their campaign finance data in apps, too. New York City, for example, created an NYC Votes app that lets users search through campaign contributions, among many other functions. Michigan has an app that lets users explore campaign finance information for candidates running at the state level. This all means people with mobile phones can access this information, whereas years ago it might have been accessible only by viewing paper documents in government buildings.

MORE DATA, DEEPER NARRATIVES

Now, developers are thinking of ways to improve open campaign finance data by combining it with other datasets, showing deeper narratives about money in politics. Chicago developer Derek Eder proposed a tool as part of the Knight News Challenge to find connections among campaign finance data, lobbying data, and legislation, allowing investigative journalists and others to find where there might be red flags. As many news stories already show, campaign finance data is often strengthened when analyzed along with related datasets. Combining these kinds of information shows the power of opening up data for analysis and could provide many more examples of the impact of opening up a wide range of datasets.

There are many more cases showing how news stories and apps are using and contextualizing campaign finance data to expose narratives of the influence of money in politics. We’ve compiled some of these in our research. As we continue to examine campaign finance data on the local level, we’ll be creating a guidebook to help states and municipalities think about best practices for collecting and sharing this information. We’ll also be evaluating how three local governments are doing in comparison to those recommendations.