What a “Lobbyists’ Lament” doesn’t tell us about lobbying

Photo: Tiina Knuutila/Sunlight Foundation

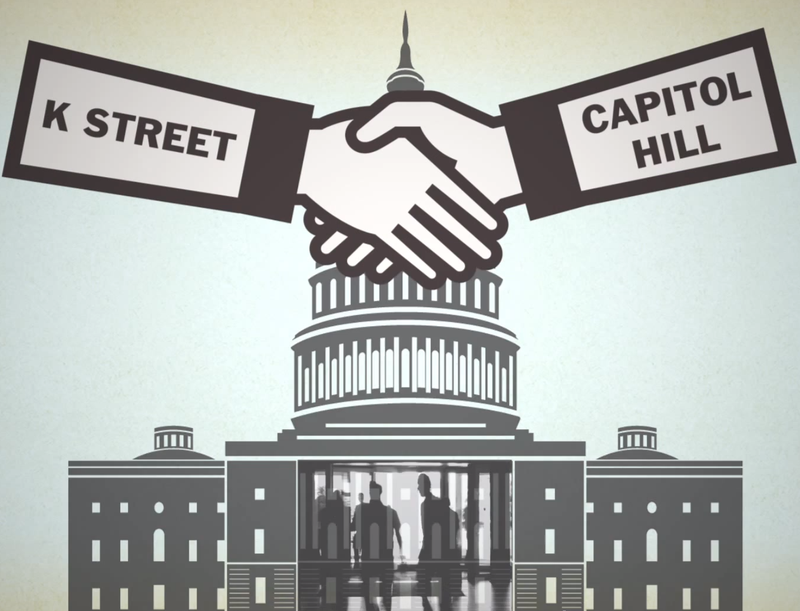

In Politico Magazine, long-time lobbyists Haley Barbour and Ed Rogers write to express their mock shock (“we’re shocked!”) at lobbyists’ low regard in a recent poll: “We come not to bury lobbyists, but to explain them.”

Barbour and Rogers’ piece, “The Lobbyists’ Lament,” is an unintentionally remarkable example of how lobbying works. It’s lively, persuasive and nothing in it is factually incorrect. As is most lobbying.

Problem is, it’s also one-sided. As is most lobbying.

And so it leads to a distorted picture of the world. As does most lobbying.

Barbour and Rogers argue that lobbying involves three parts. First, they argue, “someone has a problem, concern or desire to change something in Washington or in government somewhere.” True enough. But this presumes that all people who have a problem also have the wherewithal to hire a lobbyist. They don’t. The numbers are remarkably consistent: Businesses and the well-off dominate every possible category of participation. Chances are pretty good that you have a problem, concern or desire to change something. But chances are also pretty low that you have the money to hire Barbour or Rogers to help you change it in Washington. Or in government anywhere.

And even if you could hire a lobbyist, can you make the investment needed to put together the kind of lobbying campaign that can have a genuine impact? As Barbour and Rogers argue: “A good lobbyist needs to put together a ‘wiring diagram’ that identifies all the offices and individuals who have some sort of discretionary input over the issue in question. That group includes the obvious government offices, but can also include the media, competitors, trade associations, think tanks and other interest groups.”

Putting together that “wiring diagram” doesn’t come cheap. As they note: “These days, that diagram can grow pretty large.” True indeed! To build that diagram right costs big money. And it’s money that increasingly limits serious lobbying to the few organizations that can spend big.

Consider this: In 2012, a total of 9,323 unique organizations spent something on lobbying. But fewer than half (4,041) spent more than $100,000. The top 200 groups, barely two percent of all organizations, accounted for 44 percent of all spending. Of these top 200 spending groups in 2012, 144 were individual corporations, 37 were trade associations representing the industries where many of those corporations compete and two were business associations representing, well, business. That’s 172 out of 200, or 86 percent, of the top 200 lobbying clients that represent business interests. In 2012, 372 companies reported spending at least $1 million on lobbying. The most active, Blue Cross Blue Shield, spent $21.9 million, followed closely by General Electric at $21.4 million.

Their second point, that “you have to get a fair hearing in front of the people who matter,” is again, true. But it implies you have equal access to the people who matter. You don’t. Revolving door lobbyists do.

On one hand, most lobbyists are highly specialized subject-matter experts who lawmakers and rule-writers rely on for their expertise. On the other hand, some lobbyists trade on their connections and insider-knowledge. The latter tend to represent clients from a variety of industries and lobby on a variety of unrelated issues. They’re not technocratic policy wonks. They’re access peddlers. Hire them, and they get you in the door to make your case before the people who matter.

Guess which category former RNC Chairman/Reagan White House political director/Mississippi Governor-turned-lobbyist Haley Barbour and former Reagan and Bush I White House official-turned-lobbyist Ed Rogers falls into? (Or for that matter, consider the bios of their colleagues. It will make you dizzy with the revolving doors)

For the record, here’s who Barbour represented in 2013:

- Airbus Group

- Alliance for Quality Nursing Home Care

- American Health Care Association

- Building America’s Future

- Caesars Entertainment

- Canadian National Railway

- Caterpillar Inc.

- Chevron Corp.

- Crest Investment Co.

- Huntington Ingalls Industries

- kidney cleanse Partners

- Mortgage Insurance Companies of America

- Motorola Solutions

- Retail Industry Leaders Association

- Southern Co.

- Tenax LLC

- Toyota Motor Corp.

And here’s who Rogers represented in 2013:

- Airbus Group

- Alfa Bank

- Canadian National Railway

- GlaxoSmithKline

- Kurdistan Regional Government

- National Association of Software and Services Companies

- Raytheon Co.

- Republic of India

- Southern Co.

- State of Kazakhstan

- Xerox Corp.

If these look like the client books of highly specialized technocrats, perhaps you’ve spent too much time as a lobbyist.

Finally, they argue that lobbyists are honest. They write: “You have to tell the truth and maintain a reputation for telling the truth.” At the risk of getting too meta here, true enough. But truth doesn’t mean the whole truth.

Barbour and Rogers have written a piece that is true in that it doesn’t tell lies. But it also conveniently leaves certain truths out. It doesn’t acknowledge that some perspectives and interests purchase more advocates than others. Congress has limited attention and capacity. Many groups may have legitimate concerns before government, many more concerns that government can respond to. And they all have true facts.

What matters is which groups’ true facts get the attention of the government. The short answer: those that can afford to hire well connected lobbyists like Rogers and Griffiths.

If Barbour and Rogers are concerned that lobbyists are so misunderstood, perhaps they would support Sunlight’s proposals for increased lobbying disclosure. After all, Barbour and Rogers write: “And didn’t former President Bill Clinton once say something like: If you know what you’re doing, you’re never afraid to talk about what you do?”

If lobbying really is “like a slow-motion jury trial” — again, a totally reasonable assessment — then why not let the public see more of it? After all, lobbyists’ reputations can’t get any worse.

Finally, reporting lobbying contacts in real-time could especially go a long way toward helping to ensure elected officials get the whole truth instead of just part of the story. It would at least make it obvious when a lawmaker is only hearing one side — and give the other side an opportunity to respond before it’s too late.

But at least give Barbour and Rogers credit for calling themselves what they are: lobbyists. At least they register and file a list of clients. Maybe Barbour and Rogers will use their considerable influence in helping us achieve our goal of fuller disclosure, and expand the definition of “lobbying” to include the many shadow lobbying activities that pervade Washington.

Tim LaPira, an Assistant Professor of Political Science at James Madison University, is a Sunlight Foundation Academic Fellow.