Transparency Case Study: Lobbying disclosure in Canada

Introduction

By international standards, Canada has a fairly comprehensive and well-implemented lobbying registry. The data is machine and human readable, and it is easily accessible as bulk downloads or through a search interface that serves the needs of its primary users. Journalists and advocates, as well as those within the influence industry, all use the lobbying registry. In many ways it is a picture of how lobbying disclosure is supposed to work. At least that appears to be the case until one looks closer. While there are many admirable features of Canadian lobbying regulation, current disclosure thresholds and requirements actually create a subtly perverse incentive structure that drives activity into the shadows.

Our look at Canadian lobbying offers a few interesting lessons both for lobbying regulation and disclosure, and for technology enabled transparency policies more generally:

- Incentives matter greatly, and disclosure requirements can shape those incentives and subsequent regulated activity. In an environment where there is a presumptive advantage to non-disclosure and two substitute forms of activity with differing transparency environments, disclosed activity will decrease in favor of the more opaque.

- Both public officials and lobbyists play a role in shaping the lobbying environment and subsequent disclosure. Effective regulation and transparency requires active participation from both groups, and the law should be constructed to align their incentives to produce appropriate disclosure.

- No matter how good the tool or data release scheme, it can only be as useful as what the data itself represents. Effective transparency requires the data to be both accurate and accessible.

With the notable exception that Canada does not require the disclosure of the monetary value of lobbying contracts, the Canadian Lobbying Act requires fairly comprehensive disclosure about consultant lobbying. However, in-house lobbying by corporations and other organizations, as well as direct meetings with clients, must pass a certain threshold of activity before registration is triggered. Absent this threshold being met, disclosure of meetings or other influence activity is not required for these outside groups. This is complicated by the fact that this threshold is not strictly policed. The resulting two-tiered disclosure regime drives activity away from the types of meetings and interactions that will show up in lobbying registry records, and toward less transparent and more informal interaction between the public and private sector.

Major lobbying regulation first passed in Canada in 1989. Since then, it has been amended and strengthened successively in 1995 and 2005. The last major overhaul of Canadian lobbying registration and disclosure was in 2008, with The Lobbying Act of 2008 (R.S.C., 1985, c. 44 (4th Supp.). Among other things, this act mandated electronic filing of lobbying reports, and established the Office of the Commissioner of Lobbying, an independent regulatory commission, to oversee and manage the public lobbying registry.

According to the Office of the Commissioner of Lobbying, the act is based on four key principles:

- Free and open access to government is an important matter of public interest.

- Lobbying public office holders is a legitimate activity.

- It is desirable that public office holders and the general public be able to know who is engaged in lobbying activities.

- The system of registration of paid lobbyists should not impede free and open access to government.

Here we are concerned primarily with the ability of public office holders and the general public to “know who is engaged in lobbying activities” under the current disclosure regime. This ability is dependent on who is counted as a lobbyist, and what kind of activity is classified as lobbying. These definitions vary widely across countries. The Canadian definition, detailed below, is quite comprehensive. However, it leaves some notable loopholes that highlight the difficulties of capturing all relevant activity even within a well-designed system.

Defining lobbying

In Canada there are three classes of lobbyist, each of which is treated slightly differently. These are: consultant, corporate and organizational lobbyists. Consultant lobbyists are those who are hired by clients to either communicate directly with public office holders or set up meetings between the client and public office holders. An individual paid to communicate on behalf of a client with public office holders about any policy, rulemaking, amendment or grant/contract awarding process is classified as a consultant lobbyist and is required to register their activity under the law. Corporate and organizational lobbyists are those who are on staff at corporations or organizations and are paid to engage in lobbying activity. They can be thought of as “in-house” lobbyists, in contrast to consultant lobbyists whose work is contracted out. Organization lobbyists work in-house at non-profits, while corporate lobbyists work at corporations.

According to Katlyn Harrison, a lobbyist at the consultant-lobbying firm Summa Strategies, the law’s definition of which activities trigger registration is appropriately inclusive. She commented, “I have never tried to register for a client and not known where I could slot them in, be it policy or program, grant or contribution, legislative proposal. I have never not known where my lobbying activity would fall” (24:45).

Corporation and organization (nonprofit) lobbyists are those who work within an organization but engage in the same communication activities as those that trigger registration for consultant lobbyists. Significantly, consultant lobbyists must register if they engage in any of the above activities on behalf of a client, while lobbyists on behalf of corporations or organizations are only required to register as in-house lobbyists only if those activities “constitute a significant part of the duties” of one full-time employee equivalent. By regulation, “significant part” means 20 percent of an employee’s time.

What do lobbyists disclose?

Katlyn Harrison describes her registration process as a consultant lobbyist as follows:

There is an initial registration and then there are ongoing things that you have to do. So you register initially on the client’s behalf. You let the government know essentially who you are going to be lobbying, what the primary issues are. Once that registration is approved – and that is a general registration which more or less covers your activities – if you do arrange formal communication that requires a monthly communication report where you are asked to name specifically who it was that you spoke to about the subject on which you are lobbying.

… if we are going to be arranging meetings on the client’s behalf we are required to register. So even if we are not attending the meetings ourselves we are still required to register for that purpose (3:45).

This is essentially a three-step registration process, in which differing levels of activity trigger different reporting requirements.

First, a lobbyist must register if they intend to engage in the aforementioned activity in either a consulting capacity or as an in-house lobbyist that will cross the 20 percent activity threshold. This registration is good for as long as they are active lobbyists.

Second, lobbyists file registrations when they undertake a new lobbying campaign. The chart above shows the companies that have had the most active registrations filed in this manner between 1996 and 2013. Essentially, these registrations are a signal of intent to lobby a given set of government institutions on a given subject matter. Consultant lobbyists, who must register their intended activity each time they sign a contract with a new client, file the majority of these records. However, in-house lobbyists must register their intent to lobby as well. These filings provide a mapping from client (usually a company) to the firm they have hired, and which lobbyist within that firm is the primary consultant on the account. For both consultant and in house lobbyists, these filings include information on what communication methods the lobbyists intend to use (e.g. email, meetings), what institutions they intend to lobby, what topics the intend to focus on and whether the lobbyist on the account held a prior government position (above a specific seniority threshold).

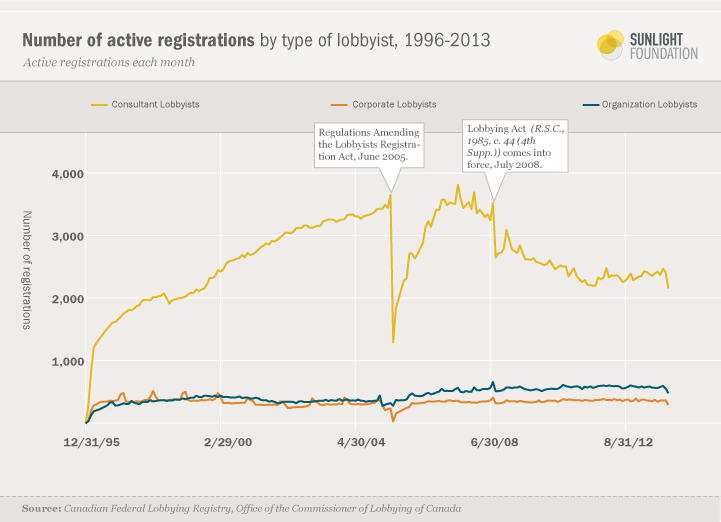

We looked at the active registrations of consultant lobbyists from 1996 to 2013, and noticed a few interesting patterns. Once the first law requiring registration of active campaigns was enacted in 1995, registration was quickly adopted and the number of active filings increased steadily until the act was amended in 2005. It appears, at this time, that a large number of lobbyists and organizations allowed their registrations to expire as the new regulations came into force. Presumably once they re-evaluated the need to register under these new conditions, most of them re-registered; the number of active registrations returned to previous levels of the next year. In the summer of 2008, we see a similar — albeit smaller — mass deregistration, again when revised regulations were implemented. However, the stricter requirements of the 2008 regulations appear to have acted as a disincentive to either hire consultants or register activity, as active registrations do not return to pre-2008 levels.

The third, and perhaps richest, form of data that are captured by the lobbying registration system are the monthly communication reports that lobbyists on active campaigns are required to file. Every month lobbyists are required to file a report that lists which government institutions and which specific designated public office holders they have contacted, when they communicated with them and the topic(s) that were discussed.

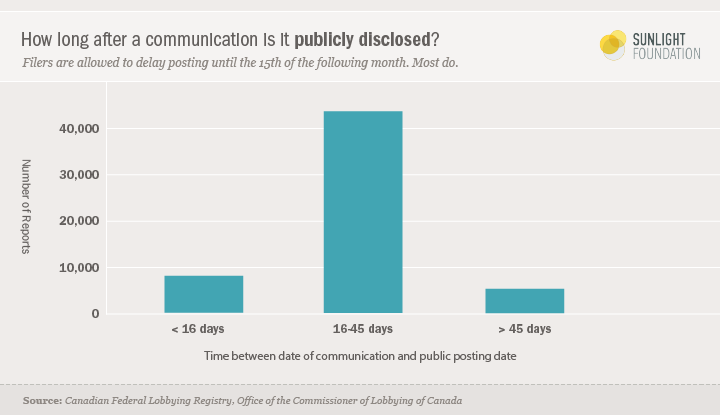

When filing communication reports, lobbyists are allowed to opt-in to a delay before those reports are made public. These reports are then published in the registry on the 15th of the following month (e.g. a communication in July would be published on the 15th of August). Some lobbyists file immediately and opt-in to this delay within the registry system, while others file delay their filing themselves until the 15th of the following month but have it go live immediately.

The communication report bulk data includes three separate dates for each filing: the date of the communication, the date it was submitted to the registry and the date the communication went public on the registry. The option delay means a theoretical maximum of 45 days between the date of the communication and the date it should go public on the registry (i.e. if the communication was on the first of the month). We looked at the lag between communications and their posting, shown above. The vast majority of communication filings appear to make use of the optional lag. Importantly, a substantial portion of communications are posted well after the maximum theoretical lag, and appear to be in violation of existing regulation.

What doesn’t the registry tell us?

The disclosure system detailed above is fairly comprehensive by international standards. Lobbyists disclose whom they work for, what the scope of that work is and who they specifically speak to as they do that work. Unlike the U.S., disclosures do not include the value of lobbying contracts or the amount of money spent on in-house lobbying. There is no monetary value assigned to lobbying activity. The Office of the Commissioner of Lobbying has indicated that they do not believe this information to be of necessary to their mission, and in general, interviewees did not feel that this was a huge shortcoming (Doyle 31:20). Several, however, agreed that dollar values could be useful as a proxy for the intensity of a client or companies interest in some specific target. Additionally, some specifics of the implementation appear to limit the influence activity that actually makes it in to the system despite rigorous requirements.

Simon Doyle, editor of the Lobby Monitor, a specialty news outlet that focuses on lobbying, noted that there is no way to tell the type of interaction which is listed in a communication report. When lobbyists register a specific lobbying campaign, they are required to list the types of communications they intend to use. Generally they indicate all or most of the available options (e.g. phone calls, written communications, meetings, presentations, etc.). When the lobbyists then file monthly communication reports associated with that campaign, they will say which designated public office holders they communicated with but are not required to specify the manner in which they communicated with them. According to Mr. Doyle, it is impossible to tell whether it is a “meeting or a phone call or an email, they just call it a communication” (7:00). Different communication types imply different levels of access to the public official in question, and would be useful from an accountability perspective.

Another notable limitation of communication reporting is that these reports only list the government officials who attended the meeting. The registration makes clear that the meeting was on behalf of the a specific client, but Mr. Doyle notes that if Microsoft were lobbying, “it will tell you the company name, [… but] you don’t know who from Microsoft is meeting with those government officials. The CEO is the responsible officer for the report, but that does not mean that they are the person who met” (8:00).

This can be quite misleading, and obscures useful data, as the seniority of the person representing the client is an important signal of the intensity of that client’s interest. Michael Geist, Canada Research Chair in Internet and E-commerce Law at the University of Ottawa, pointed out how this is limiting:

[It] is far less useful than it could be because it matters whether or not it was the president or CEO of an organization or whether it’s just a policy person. You know, what level do you have to be to get that meeting with the minister and is it someone at that very high level or is it people who are seen as somewhat lower down in the organization and their ability to get meetings, are themselves, they get people who are a bit lower in the pecking order as well. The fact that, it’s not quite shrouded, the meeting itself is not shrouded in secrecy, who, the specific people who were in attendance sometimes can be (12:45).

Essentially, a meeting with the CEO means more than one with a junior VP.

Mr. Geist noted that despite the fact that It’s not as useful as it could be because you don’t know all the specifics: “There is a bit of tea leaf reading, I guess, around some of the entries but that information [in communication reports] can be really useful” (9:28). He continued by offering an example:

In the copyright context, you have an instance where the MPAA (Motion Picture Association of America) will come up to Ottawa essentially for a day of lobbying and you can trace their movements. It’s a month later, but a month later you can see exactly how they went from office to office to office so you get a sense of who they think is influential and who they are trying to influence and then you can also file access to information requests for any information related to those meetings (11:00).

These above aspects of the registration system leave some important information unrecorded. However, the more serious problems with the lobbying act come from how disclosure interacts with the 20 percent activity threshold for registering as an in-house lobbyist. For public office holders there is a five-year ban on lobbying after they leave their government position. Jim Patrick, president of the Government Relations Institute of Canada, pointed out that technically this moratorium is on registering as a lobbyist, not on engaging in any lobbying activity. He observed that the fact that an individual must spend at least 20 percent of their time lobbying at a corporation or organization to trigger registration creates a sort of loophole in this moratorium for former office holders: “You can lobby as long as you: a) work for a corporation, not a consulting firm, not an organization; and b) only do it 19 percent of the time” (Patrick 1:30).

Concern over how this threshold can be used as a loophole to allow former government officials to engage in lobbying activity without registration for corporations or organizations was shared widely among our interviewees (Doyle 13:30; Harrison 12:00).

As Mr. Doyle described it:

There are definitely cases where former government officials will go work in-house as a government relations official. […] We don’t really know what they are doing, but they will say that they are giving advice. One recently actually, there was a guy who left – there was a story in the hill times, a guy went from government to work for Barrick Gold (15:00).

Katlyn Harrison described how the 20 percent registration threshold for organization and corporate lobbying can leave a lot of activity unaccounted for.

For example, the executive director of an association, they may spend 3 days a month looking on how to improve their government relations. That executive director, even though they have interface with government, would not be required to register because it is less than 20% of their time. So how much is 20% of someone’s time? It’s a little bit flexible and it can be bent on either side to make someone choose to register or choose not to register (12:00).

Activity of this kind will not show up in anywhere in the registry. She continued by pointing out that “there is a perceived advantage to not registering if you are dealing with something that is particularly sensitive that will be less than 20 percent of your time” (Harrison 13:00). It is certainly worth noting that according to current regulations, organizations and corporations must register if the collective efforts of the entire organization’s staff comprise the equivalent of 20 percent of one person’s time. However, this provision seems to be largely misunderstood, and the data does not seem to bear this out.

Disclosure is additionally complicated by a fact about how lobbying is conducted in Canada that was pointed out by several interviewees. According to Ms. Harrison, “it is far less common [than in the U.S.] for consultant lobbyists, at least in Ottawa, to do a lot of lobbying” (8:40). A lot of the work that they do is, rather, to work their networks to organize meetings for their clients, and advise their clients on how they should appeal to the government officials they speak to. She added that, “if they get a meeting for their client, they are going to let their client do the actual talking. They are not going to be doing the lobbying for them” (9:30).

Apparently, public officials often share this preference as well. Ms. Harrison described the attitude of some of the public officials as follows:

[T]here is a perception sometimes from MPs and staff […] to avoid dealing with registered lobbyists because if they are not following all the rules or if they think that they’re not following the rules they don’t want to get into any trouble. [It is] self protection involved on their part. It’s not uncommon that we have certain MP offices or staff come back [to us] and say: ‘Yeah, got your meeting request but I would really like to get this from the client directly.‘ Because they just prefer to interface directly with the client and I believe that that’s mainly as a result of just wanting to be exceptionally careful about the rules (31:20).

Jim Patrick offered a similar summary of the position of many in government with regard to contract lobbyists as, one in which they think “if your client has an issue with government they want to discuss they should come discuss it” (4:00). He suggested that — perhaps because of some risk aversion following scandals years ago — government officials are wary of contract lobbyists:

[The] view of government goes, you are never really sure on whose behalf they are talking, maybe they have got another client with an interest, but they are telling you they have got a charity they are advocating for but really they have got a corporation they are not telling you about. It is that kind of suspicion from the governments point of view, rightly or wrongly, that has led to that practice [of preferring to speak to the client directly] (5:00).

Furthermore, if the government initiates contact with a company or organization – whether they are contacting a registered lobbyist or not – the ensuing interaction does not need to be disclosed. The idea behind this is that there should not be any constraint on the government’s ability to seek out relevant information. However, this creates more opportunities for undisclosed lobbying activity, particularly when the interests of both public office holders and private interest align. Mr. Patrick noted that this can be a particularly problematic provision.

It is often misunderstood. People try to game the system […] they will send an email to someone in government to say please call me and then the government calls them and they say: ‘Oh, they called me so I don’t have to report it.’ It is not who calls who, it is who initiates the call (or communication). [In this example] it is the email that initiates the communication (10:10).

This behavior, if systemic, can lead to significant unreported lobbying activity. If a client takes a meeting with a public official, and the client representative spends less than 20 percent of their time interfacing with government, they will never show up anywhere on a communication report. Officially, calls made by a consultant lobbyist to set up those direct client-to-government official meetings should be reported, but apparently this does not always happen. There seemed to be some confusion among our interviewees about how this is handled, which did not inspire confidence in high rates of reporting for this type of activity. Jim Patrick also noted that even if that consultant lobbyist’s call does show up on a communication report, it may not indicate on which client’s behalf it was made. The consultant lobbyist call to book the meeting may show up on a report. He called this “one of the gray areas” of the reporting requirements (7:25).

Enforcement

According to our lobbyist interviewees the rate of registration among career lobbyists is high, and enforcement by the Office of the Commissioner of Lobbying feels like a credible threat.

Ms. Harrison offered that, as a consultant lobbyist who began work after the Federal Accountability Act was implemented, proper registration and compliance has “been something that has been drilled into me as something that is exceptionally important to follow and I can say that for the other – my colleagues here – that it’s something we take very seriously” (49:50). According to Mr. Doyle, “the default for most lobbyists is that if they talk to government at all is that they just register,” but “You can get away with being pretty vague about what you are talking to government about” (16:40). Nonetheless, he concluded that “aside from the 20 percent rule, the registry captures a lot.”

The Officer of the Commissioner of Lobbying, has investigative powers but not powers to lay charges or arrest anyone. If the Commissioner finds lobbyists of firms to be in violation she can then refer the case to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. This is quite rare. In fact, the first charges ever were filed last year. However, according to Jim Patrick, “The commissioner does have pretty heavy moral suasion power and being named in a report to parliament saying that you are a bad lobbyist is kind of a death sentence to a lobbying business” (11:00). Ms. Harrison confirmed that being named in such a report has strong professional implications: “It makes its way around the lobbying and the government relations community pretty quickly who those people are” (51:00).

In general, interviewees believed that registration rates are high and people tend to disclose, particularly among consultant lobbyists where there is no “significant time” test on lobbying activity. However, Sean Holman, journalism professor at Mount Royal University, noted that it is quite hard to know this for sure, as “it is difficult to comment on the absence of something, and what that means.” Especially in the context of the 20% registration threshold for corporate and organizational lobbyists, the regulation depends in large part on a presumption of good faith and compliance (11:00 – 14:00).

Data use

According to interviewees, in recent years the registry has been made quite usable for its key audiences of journalists and public affairs professionals. New registrations and communication reports are easy to view online through the registry, and the search function is simple and effective. Sean Holman and Simon Doyle both described their routines when covering the lobbying beat:

My morning routines would be to wake up and check a variety of different disclosure websites to see whether or not there had been anything interesting that had been posted over the last day. Two of those websites were the BC lobbying registry as well as Canada’s lobbying registry. […] They led to a fair number of stories (Holman 6:30).

Two of the most regular things that we do are the new registrations – which are posted every day. So we just check those every day and based on if there is enough for a story we will do something on it. And that is as simple as going into the registry and there is a thing you click on” ‘new registrations.’ […] And for communications reports […] we also do those, but those are only released each month. So January’s communications will be released the 15th of the next month […] that is one of those competitive information issues. [Communications reports] are just another part of the website you click through (Doyle 26:00 – 28:00).

The level of information captured allows journalists to look at multiple different aspects of a filing, Mr. Doyle expanded on his description of his reporting practice, noting that after using the search function he would usually delve deeper into the data.

[I]f there was anyone that I found particularly interesting or any company or organization I would check that file out and see what was actually in the file. And I would also take a look at the bulk data — how many lobbyists were registering, who they were targeting etc. etc. So, I looked at it from a variety of various different angles (Doyle 28:00).

For more data intensive stories, like year-end reports on lobbying activity, Mr. Doyle said that they might download the bulk data and conduct a more systematic analysis. However, using the bulk data can present a significant hurdle for those less experienced in data work:

[I]f you want to export all of the communications reports they don’t allow you to, you know, conduct a search and then export that search. What you have to do is that there is one bulk data export that goes from now back to when the registry was created in the 90s. At the end of every month they update that bulk one, so you have to export that whole thing, which is everything that has ever been registered, and then try and do something with that (Doyle 5:45).

Bulk data is released as a download of machine-readable tables (CSVs) and is fairly well documented in a data dictionary that is included with the download.

The bulk download is a set of relational tables, tied together through a variety of entity and transaction/report IDs. Using these IDs to filter the filings is certainly possible, but requires some degree of facility with a statistical computing language like R or high level programming language like Python or Ruby.

Lobbyists also use the registry, viewing it as “a strategic resource for companies.” This is especially true in among consultant lobbyists, where lobbyists “pay attention to who just signed up which client” (Patrick 14:00). Mr. Patrick offered a recent example from the telecommunications industry, in which he works. He saw in the new registry that a “few months ago Verizon engaged a consultant lobbyist after months of denying they had any interest in expanding into the Canadian market.” He noted that the registry doesn’t tell him “exactly what Verizon’s ask of government is, but it certainly seems that they have an interest in the Canadian market – we can draw at least that conclusion” (Patrick 15:00).

Impacts

The view of our interviewees was generally positive of the lobbying law and the effectiveness of the registry. Mr. Doyle summarized his view of the law’s impact:

I think it has made Canada’s lobbying a lot more transparent. We are still a very, very secretive country when it comes to government, but I definitely sense that lobbyists are more open about their work now than they were say in 2004 (12:00).

He added that the five-year ban on being a lobbyist after working in the government has “definitely changed the so called ‘revolving door’” (12:30).

The successful implementation of the online registry, its search functions and bulk data have altered the ecosystem of lobbying registry data use. The registry has lowered the barriers to use significantly.

Improvements to the registry have made accessing lobbying data much easier for journalists to use. Now the “registry is way, way more user friendly than it used to be. It used to be really clunky and really, really difficult to understand and to use […] We can do most of our work just online searching it, we don’t have to export stuff,” said Mr. Doyle. Before these improvements there was “a little bit of an industry in export and data manipulation of the registry because it was so not user friendly,” which has since disappeared because it is easier to use the system (Doyle 33:40).

Mr. Holman agreed on the usefulness of the registry, with the important caveat that it still leaves a lot unknown. He summarized:

Government in this country to a certain extent […] is somewhat of a black box. So in order to actually figure out what exactly is going into that black box, what is actually going on in that black box, it is helpful to know what is going into it and what is going out of it. And a big part of that is the lobbying that goes on. So I suppose that is why it was part of a regular check for me every morning (Holman 6:30).

Conclusion

Despite the generally positive reviews of the current system, concerns over who registers, under what circumstances and what communication they have to disclose clearly create a perverse system of incentives. The mutually beneficial incentives of clients and public officials drives lobbying activity away from meetings by consultant lobbyists which require reporting and towards more informal meetings directly with the client, which may not be disclosed. Because of apparent risk-aversion over running afoul of registration requirements, activity is made more, rather than less, opaque. This is not the intent of the law.

To maximize disclosure, a few relatively small changes to the registration and reporting requirements would make a big difference. The 20 percent time threshold for triggering registration as organization/corporation lobbyists should be removed. Any representative from a corporation or organization who takes meetings with members of government should file a communication report. Furthermore, all individuals in attendance of these meetings should be listed in communication reports, rather than appearing under the client CEO’s name.

Under the current system of two-tiered system of disclosure, the incentives of both those who would like to influence the government and those within the government is to engage directly without consultant lobbyists as intermediaries. Beyond the qualitative description we received from interviewees, there is no good way to know the extent to which this is actually taking place, precisely because this sort of activity is not reported. Normalizing registration between consultant and in-house lobbyists would remove this incentive to avoid disclosure by having clients to lobby directly instead of consultant lobbyists. Ultimately, this would strengthen the lobbying law and reveal more about how the government and private sector interact without increasing penalties, enforcement costs or creating an undue burden on the legitimate interests of the private sector.

Supporting materials

Katlyn Harrison – Consultant Lobbyist at Summa Strategies

Simon Doyle – Editor of the Lobby Monitor

Michael Geist – Law Professor and Canada Research Chair in Internet and E-commerce Law at the University of Ottawa

Sean Holman – Journalism Professor at Mount Royal University

Jim Patrick – President of the Government Relations Institute of Canada

Tom Marshall – Board Member, Transparency International Canada