A lesson learned from the beleaguered NTIS

“Our goal here is to eliminate you as an agency.”

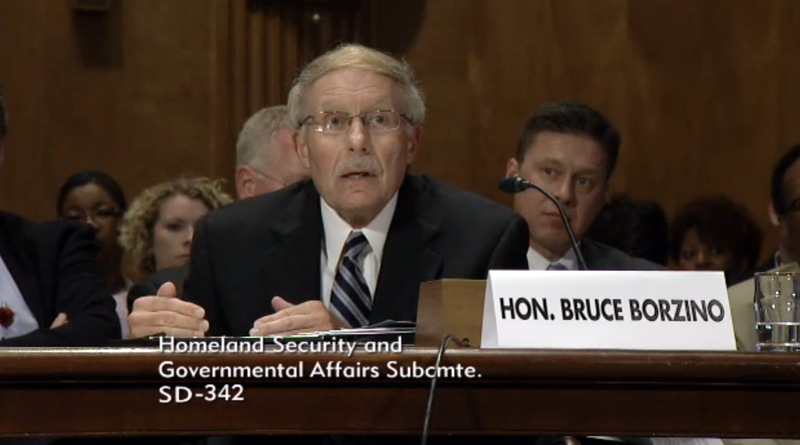

Sen. Tom Coburn’s terse statement towards Hon. Bruce Borzino, the Director of the National Technology Information Service (NTIS), succinctly summarized Wednesday’s Senate Hearing on the future of his small and beleaguered branch of the Department of Commerce. The NTIS once endeavored to provide a centralized and organized location for government documents. Now that its pay-to-access document library has become virtually obsolete as other agencies self-publish information for free, the NTIS’ very existence is being called into question by Sens. Claire McCaskill, D-Mo., and Coburn, R-Okla., the chairs of the Subcommittee of Financial and Contracting Oversight.

“Where you’re lucky enough to click is the difference between free and paid government information,” McCaskill noted. But a confusing mix of government data repositories both fee and free was only the beginning of the senators’ criticisms. The two slammed the NTIS’ significant access costs for both taxpayers and government entities, which they perceived as an unfair burden on taxpayers and wasteful government spending. Indeed, the cheapest and most limited subscription to the NTIS library costs $2,100, and the NTIS charged the Department of Commerce — its own parent entity — $288,000 in access fees in FY 2013. The 150-person agency, operating on $66 million in taxpayer dollars, struggles to defend itself against claims of errant spending, and its additional library access fees for taxpayers — who already pay for the service’s existence — appear equally egregious.

The NTIS library’s remaining strength may last with its size. Host to 2.8 million federal publications and, according to Borzino, an additional 30,000 titles added annually, this repository overshadows the size of other information repositories like Data.gov, which currently hosts just over 111,000 datasets. Despite charging access fees, the service has struggled to adapt its infrastructure to technological advances. The service is roughly a decade behind on technology infrastructure — it used microfiche as its main information dissemination format until a decade ago — and only recently moved online. Although the NTIS originally endeavored to centralize and index government data for the public, a goal critical in open governance, the agency’s goals are beyond what its underdeveloped technical abilities can accomplish.

In spite of indexing and centralizing of government information, public demand for the NTIS’ expensive library remains weak, with other government agencies as its main subscribers. In recent years, the NTIS has also expanded to assist with web services like hosting and connecting government entities to contractors. Sens. McCaskill and Coburn took fault with this middleman position, which they found duplicative of the General Service Administration’s work, but more expensive and wasteful. Today’s NTIS, with a cumbersome and expensive documents library as well as redundant inter-government services, is a far cry from the NTIS President Harry Truman first established, which would “promote the nation’s economic growth by providing access to information that stimulates innovation and discovery.”

Coburn officially calls for the end of the NTIS in his proposed “Let Me Google That For You” Act, a cheekily named bill representative of the new information ecosystem in which the NTIS struggles to adapt. His bill is far from the first attempt to close the small agency: the Department of Commerce also pursued shuttering the NTIS during the Clinton administration. The Government Accountability Office (GAO) has criticized the NTIS’ efficiency in reports dating back to 2000. The GAO even asked the NTIS to stop publishing its reports for fees, given that it now publishes them on the GAO website for free. The fate of the agency lies in the fate of Coburn’s bill, which still sits in the Senate Committee for Commerce, Science, and Transportation. The end of the NTIS will not trigger a sudden and massive loss of government information: a 2012 GAO report estimated that 74 percent of the NTIS library is readily accessible through other public sources.

As the NTIS’ existence hangs in the balance, mired in allegations of wasteful spending and inefficiency, this outdated attempt at a centralized and indexed government information bank may soon come to an end. Yet its original vision of a centralized clearinghouse of government information remains as necessary as ever, as the internet facilitates government data disclosure but not necessarily its organization. The possible end of the NTIS is a call for more effective information and data disclosure strategies among government agencies. If the Senate deliberates on the “Let Me Google That For You” Act, they must not only think destructively in terms of abolishing the NTIS, but also constructively about how that agency’s goals can be better accomplished in the future.