Consent decrees open police data, but for a limited time only

Who polices the police?

(Photo credit: Joe Gratz/Flickr)

Well, since the enactment of the 1994 Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act a portion of that responsibility has gone to the Special Litigation Section of the Civil Rights Division of the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ). When a local or state police department exhibits a pattern of unconstitutional practices or policies, Section 14141 of the 1994 bill gives the DOJ jurisdiction to investigate and litigate that department.

These investigations often result in an agreement between the DOJ and the police department called a consent decree (also known as a ‘memorandum of agreement’ or ‘settlement agreement’). This May, Cleveland entered into a consent decree after the DOJ reported “systemic deficiencies and practices” that contributed to unreasonable police use of force throughout the police department. The consent decree outlines requirements that will make policies, procedures, audits and select police data publicly available. Specifically, the agreement encourages transparency for use of force justifications, the establishment of a 13-member citizen advisory committee and revisions to search and seizure policies.

In March, the Ferguson Police Department (FPD) received findings from their Section 14141 investigation and is currently negotiating a consent decree with the DOJ; alike to Cleveland, FPD also received recommendations to improve the openness of its data. If FPD does not settle with the DOJ, they could risk dissolution or further litigation.

Consent decrees can help achieve greater transparency and accountability in policing because they often require departments to institute new policy, collect new data and report data publicly. New Orleans’ 2012 consent decree was particularly expansive, requiring the police department to improve the quality and availability of police data, policies, manuals, reports and audits. The policy changes required by the consent decree opened a multitude of police datasets, making New Orleans a leading city in open data and police accountability.

However, consent decrees and their associated federal oversight eventually end. And when this oversight is gone, the reforms instituted under the consent decree often dissolve.

Consent decree longevity

For example, the Rampart Scandal of the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) lead to the implementation of a consent decree requiring the collection and public availability of stop and frisk data. However, the LAPD’s consent decree has now been lifted and that data is no longer publicly available, with the last report dated 2006.

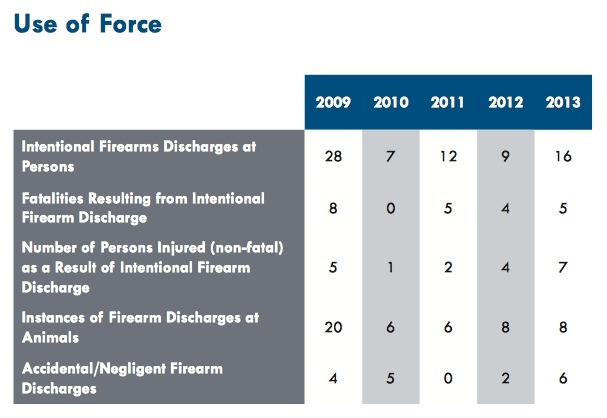

In 2001, Washington, D.C. entered into a memorandum of agreement with the DOJ after the Washington Post reported that the Metropolitan Police Department (MPD) killed more people per capita than any other major city police department. Unlike most DOJ investigations, this one was requested by MPD’s Chief of Police at the time, Charles Ramsey. This request resulted in a consent decree requiring the department to make quarterly reports on use of force statistics and complaints publicly available. The required quarterly reporting spawned the Force Investigation Team, which was later dissolved once the decree had expired as part of a “departmental reorganization.” Today, without a consent decree binding MPD to release use of force statistics, the only publicly available use of force data comes out of two annual reports — from the Office of Police Complaints and the MPD — that do little beyond reporting annual counts.

Chart of annual use of force statistics from Metropolitan Police Department’s 2013 annual report (Image credit: Metropolitan Police Department)

The New Orleans Police Department (NOPD) is finding opportunity outside of its consent decree to open data through its participation in the White House’s Police Data Initiative (in which Sunlight is also proud to participate) and a meeting at the White House addressing how to use technology and data to improve community policing. In this meeting, the NOPD made a commitment to release use of force data, car and body camera metadata, results from disciplinary investigations and both pedestrian and vehicle stop data. NOPD made this commitment “because people are asking for that information and [they] want to be transparent about it” and that releasing this data will “build legitimacy and build trust in police and the community,” according to NOPD’s Superintendent Michael Harrison.

In cities such as New Orleans, Los Angeles and Washington, D.C., consent decrees have been responsible for opening police data that may not have otherwise been made public. These public datasets are integral to police accountability and building community trust, but unfortunately are only guaranteed while federal oversight exists — as evidenced in Los Angeles and Washington, D.C. While consent decrees are powerful, change within a department must be systemic and well accepted, or else the department may abandon reforms in favor of cost-reduction or traditional practice.

NOPD is aware of this challenge and has committed itself to establishing a police culture that ensures long-lasting adoption of consent decree reforms.

It’s my job, along with our entire executive team and command staff team […] to change our culture…I think the systems of accountability that we’re building and implementing are the kind of systems that are strong and are flexible to change over time as things change with this police community. I’d like to think these systems of accountability will always be there, whether I’m the chief or not, to make us the kind of police department that we promised the citizens we would be.

In addition to the necessary intra-departmental cultural change, community buy-in is also important in ensuring lasting reform adoption. NOPD Deputy Chief of Staff Jonathan Wisbey agrees:

Once you start establishing expectations with the community, by providing data, it makes it very difficult for someone in the future to go back and say this thing that we’ve provided for years…we’re no longer going to do so.

Of course, consent decrees do not guarantee greater transparency or data availability. Some consent decrees, like Detroit’s (ongoing from 2003) do not include requirements to make data publicly available. Although Detroit’s consent decree requires the department to collect new data and statistics, they are only required to report them to the consent decree monitor, the City and the DOJ. Instead of hosting their own crime statistics, the Detroit Police Department (DPD) links to city-data.com. We were unable to identify the source of this data as city-data.com does not cite sources and did not reply to our inquiries. Due in part to the consent decree and an Executive Order establishing Detroit’s Open Data Initiative earlier this year, the City of Detroit holds DPD crime data and has recently made it publicly available on the City’s open data portal alongside data from eight other agencies. Detroit is a prime example that consent decrees, while often helpful in increasing transparency and accountability in policing, are just one of the methods by which a city can open its police data.

Cost of consent decrees

While there are many benefits realized from consent decrees, their implementation is often met with resistance over associated costs and administrative changes. Consent decrees can cost a city millions of dollars a year — and last many years — causing government and public concern over associated costs of implementing required reforms.

New Orleans’ 2015 budget includes $7.3 million to cover the costs of implementing of the city’s consent decree. In 2014, Seattle Police Department spent $5.8 million on consent decree implementation. Cleveland’s recently established consent decree was met with financial concerns as the consent decree’s requirements, which include adopting updated technology, hosting more trainings, hiring new staff and establishing external agency monitoring, will cost the city millions. Some have argued that, while expensive, the implementation of consent decrees may reduce civil liability and be a worthwhile long-term investment. Further, a consent decree can help a department get the resources they need when they would otherwise be met with pushback (page 34) from the city or unions.

Despite the promise of reduced civil liability and better resources, officers do not always welcome the intrusion of the federal government on their agency. Because the purpose of a consent decree is to reform police department policies and practices, the behaviors of police officers take center-stage. Officers often view these agreements negatively and resist suggested changes in favor of traditional practice.

It’s often hard to reform police departments without external intervention…Institutions are resistant to change. None of us like to have somebody outside telling us what to do. And police departments are especially that way.