Why are some cities so good at releasing open data? Pt. 2

Last week, we looked at some of the best performers on the US City Open Data Census and the policies that helped ensure their top-notch data accessibility. However, there are occasionally perceptions that open data is for cities with special advantages. The cities analyzed last week, Austin and Las Vegas, are both large, each with 500,000 to 1 million residents. Both cities likewise have extensive resources at their disposal, reporting yearly expenditures in the billions. This makes it easier for them to support the starting costs of an open data program. How can a smaller city with fewer resources possibly achieve the open data success of major urban areas like Austin and Las Vegas?

Yet for the all the small cities looking to implement strong open data practices, there’s plenty of reason for hope. Hartford, Conn. — whose community members note is smaller than the Denver airport — ranks high in the Open Data Census, with good public access to data on crime, construction permits and other areas. Releasing data onto the web involves some expenses, but Hartford didn’t need billions in tax revenues to develop an effective open data program. Instead, Hartford’s open data success can be partly attributed to something that did not require a large population or budget: a well-crafted executive order, issued in 2014 by then-Mayor Pedro Segarra. The order covers many of Sunlight’s open data policy basics: It calls for a centralized “authoritative” open data portal; demanded “widely accepted, nonproprietary, platform-independent, machine-readable method[s] for formatting data”; and presses for ways to make Hartford’s data easy for private users to process automatically. The executive order is also serious about implementation, insisting on clear timelines for data publication and for open data monitoring. The executive order even looks beyond the city itself, encouraging Hartford to “develop agreements with regional partners” about data access.

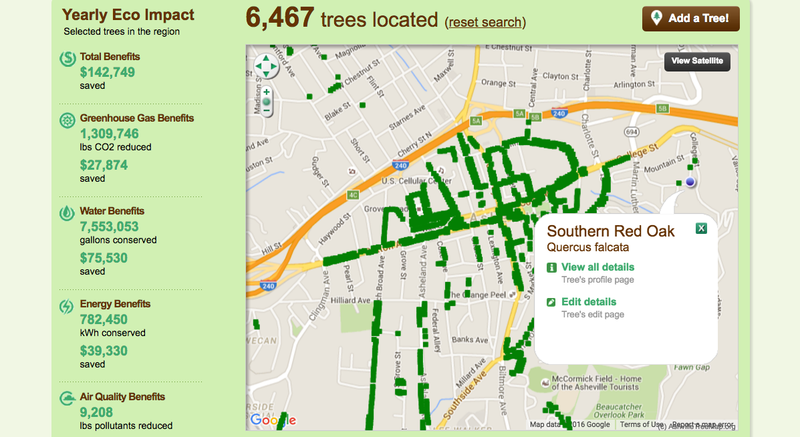

Asheville, N.C., ranks as another city with remarkable open data success. With a population of 85,000, Asheville is less than a tenth the size of Austin. Nevertheless, Asheville boasts an impressively strong open data policy, which helps shape and reinforce the city’s open data access. The policy mandates machine-readable data formats, regular updates to datasets, a centralized data catalog and a guarantee of “free re-use” for any dataset. To keep the open data program in top shape, Asheville’s policy calls for a review by city staff “every six months … for the first two years after this policy … and once every year thereafter.” Subsequently, Asheville’s open data has had interesting applications. City residents now enjoy better maps, find better parking spaces, check their recycling and think more about trees, among other things.

Of course, there’s still room for both cities to improve their policies. Though Hartford’s policy explicitly calls for “automated processing” capabilities for its data, Asheville’s policy leaves automated processing and application program interfaces (APIs) out. Likewise, Hartford could learn from Asheville’s data licensing provision, which ensures that people can freely use city data. Both could further strengthen their open data policies by requiring the cities to publish metadata, to make data available in bulk and to establish methods of prioritizing data releases. In addition, having a policy is not the same as carrying it out, and both cities should monitor to make sure their policies are well implemented.

Nevertheless, the growing success of open data in Asheville and Hartford is especially notable in light of broader trends. A city’s population is positively correlated with its Open Data Census score, and having a larger population can predict whether data in a census-evaluated city is timely or available in a machine-readable format. But as Asheville and Hartford highlight, a city hardly needs an enormous population in order to create a powerful, effective open data program.