Using public data to improve policing in Uganda

The Uganda Police Force has been continuously ranked as one of the most corrupt institutions in Uganda, and was identified as the most corrupt East African Region institution in the Transparency International East Africa Bribery Index. To its credit, it does have a promising legal framework, including a national information access law and law mandating discipline for police misconduct. The work now is to make those legal requirements work for the people of Uganda.

The people of Uganda deserve law enforcement agencies that are accountable and transparent. With the opportunities created by the 2006 Access to Information Act it’s possible for them to move forward by providing useful public information. There are some signs that the police are trying to make progress, principally with their publication of information about the public’s complaints. While this is a good first step, it’s insufficient. The quality and timeliness of this data must improve. In addition, police must work more effectively with the media to ensure that their information is getting out to a public which is unlikely to be able to find their information online.

What are Uganda’s police currently doing?

Currently, the Uganda National Police is making an effort to disclose information to citizens using social media sites, the police resource centre website, publications and the media. The police website offers a FAQ which provides information on how to contact and report cases to the police. The UPF publishes annual crime reports providing details of work conducted in a specific year as an accountability practice to Uganda citizens, and they work with communities to solve problems of crime and insecurity in communities through community policing.

Despite these modest improvements, information shared by the police appears mainly aimed at public image building instead of use by the general public in their demands for police accountability. Information on police social media sites is related to police events, upcoming activities, and recruitment and other milestones achieved. Uganda’s police website FAQ provides useful information on contacting and reporting cases, but also lacks information on how to receive feedback from submitted complaints. A good practice for promoting transparency and accountability in any environment is to maintain an effective and timely complaint response system to inform complainants about the status of their complaints. While Uganda’s police provides information on where and how to lodge a complaint to the force, there is no clear criteria for when or whether complainants will receive any feedback on lodged complaints.

The Uganda National Police has a clear legal responsibility to investigate and respond to public complaints. Information relating to reporting and receiving feedback from police can be found in the Police Act where it’s noted that the force is obliged to set up a public complaints system that allows any member of the public to file a written complaint regarding bribery, corruption, intimidation, neglect, nonperformance of duty or other police misconduct. According to the Police Act, the public should address complaints to the most senior officer in the district or the Inspector General. That officer is required to make an investigation into the matter and keep the complainant informed of the outcome of the case.

While this appears smart on paper, in practice most citizens never know whatever happens to their cases after reporting to police. People assume that their complaints disappear in police bureaucracy and never get investigated. Although the broad framework for disciplinary systems is set out in national law regarding the police, the information relating to details about how these systems work in practice are rarely made public.

One of the ways that the Uganda National Police has tried to provide feedback about complaints is within their annual criminal reports. Unfortunately, these reports are often delayed. For instance, 2014 is the most recent annual report for the force. Thee report provides good information relating to older cases received, investigated and forwarded to court, but the publication timing makes the information irrelevant in 2016. Sunlight refers to this a transparency theater, because these reports disclose delayed information, making it difficult to use this data to hold police accountable.

Further still, while the Uganda Police Annual Crime reports can be accessed on line on the police website, not all Ugandans can access them simply because they lack access to the internet. Only 19 percent of Uganda’s population has access to the internet. Eighty-one percent of citizens who cannot access the internet are ultimately left in the dark regarding police operations and performance. Knowing that poor internet access in Uganda is associated with poor infrastructure, prohibitive costs, and poor quality of service, it’s too high a bar to require the public to access police information only through online methods. By just publishing information online and not working to distribute it further, the Uganda Police Force essentially provides only Ugandan elites access to their information.

To help media report on police data and spread the word to those who lack internet access, information released by police in those annual crime reports would benefit from contextualization and analysis. The reports proffer numbers and figures which lack narrative explanation. The police do not explain the compelling stories behind the numbers, describe the change year over year, or even offer ongoing information on pending cases for the previous years. It would be significant for the police to cumulatively provide information for not only cases received in a present year, but throw some light for cases pending in the past years. That alone would showcase police commitment and accountability towards enforcing law and order as well as improving service delivery in Uganda.

Some of the issues can be remedied by a more effective presentation or formatting of the data. As seen in the table below, the data compiled from the police website does not flow consistently from one reporting period to the next. The overall picture of what happens to cases in the previous years is lost. For the public, the most important issue is not the specific level of work undertaken by the police in the year but the actions and outcomes behind those the figures. Disclosing such information will not only serve as a positive transparency and accountability practice for the Uganda Police force but also restore citizens trust in the force.

| 2007 | 231,000 | 124,000 | 46,000 | 107,000 |

| 2008 | 287,000 | 119,072 | 46943 | Unavailable |

| 2009 | 282,401 | 65,809 | 37,783 | 65,809 |

| 2010 | 262,936 | 99,917 | 29,282 | 70,635 |

| 2011 | 268,811 | 99,321 | 43,813 | 55,508 |

| 2012 | Unavailable | Unavailable | Unavailable | 51,985 |

| 2013 | 251,409 | 99,959 | Unavailable | 51,377 |

| 2014 | 258,771 | 103,720 | 44,087 | Unavailable |

Uganda Police should work with media to improve public perception of police transparency and accountability

The Uganda National Service Delivery Survey of 2015 found 75 percent of Ugandans identified the police as the most corrupt institution in Uganda. This was because the police force was criticized for bribery, fraud and extortion, but poor access to their methods of information disclosure likely exacerbated these issues. Corruption and good access to police information seem logically connected. A weak complaint feedback mechanism and poor information disclosure methods reduce the possibility to fix all kinds of problems, including bribery, fraud, and extortion. With a weak disclosure system, culprits can freely manipulate the system while damaging the transparency and moral fabric of the force. If the Uganda Police Force makes full and timely information more accessible to the public, there will be a narrower range of opportunities for the mismanagement and corruption within the system. As democracy relies on the traditional value of openness and participation in governance, the right to access information lays the foundation for a truly democratic environment — and the lack of it aids corruption.

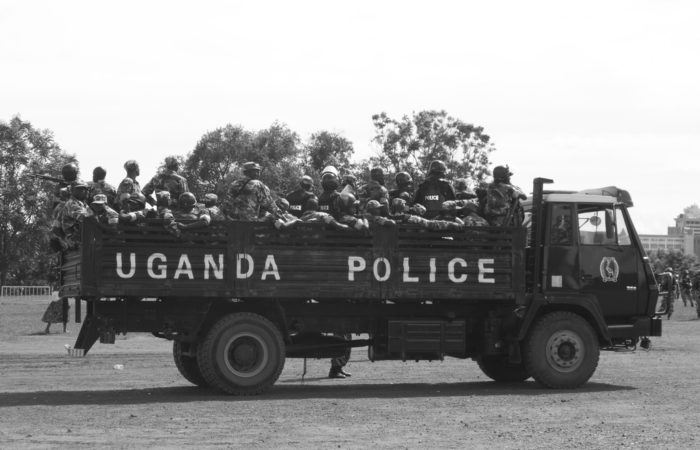

In Uganda, most citizens rely on media as source of information. Radio is particularly important; 64 percent of Ugandans get their news by radio. However, media freedom is still subject to statutory and regulatory restrictions as well as police sanctioned attacks and interference. Ugandan journalists continuosly face intimidation and harassment from the police force. They have been beaten, blocked from accessing news scenes, pepper-sprayed, arrested, detained and released without any charges against them. Others have been physically assaulted by the force as they relayed events live. Assaults on journalists can be rightfully interpreted by the public as an effort by the police to hide information and deny Ugandans a right to know what is happening in their country.

Since the media provides most Ugandans with information about government, an improved relationship between police and media could improve police information disclosure efforts, restore citizens’ trust in the force and improve its credibility before Ugandans. There is a good possibility that this could also reduce police corruption as the media help serve as a watchdog. With better relations with the police, Uganda’s media can improve public access to the information in the annual crime reports since they can provide the information in a way that most Ugandans can access.

When citizens lack information, they are unable to voice informed opinions. When they are in the dark on specifics, they can’t influence policy priorities or properly access available public resources. The best weapon of a dictatorship is secrecy. The best way to achieve a democracy is with the tools of openness. The media can serve as a driving force in the openness journey of Uganda’s police force, leading to a restoration of its credibility in the public eye. Uganda’s Police Force should consider operating based on the principle of openness because corruption is less likely to thrive in open societies and institutions. Conversely, the lack of public information contributes to corruption.

The Access to Information Act does not exist merely to satisfy curiosity, but to reveal critical information and to achieve public accountability. At the same time, the practice can restore confidence and trust in the police by demonstrating their willingness to be held accountable.

When such information is easily available for scrutiny, people are empowered to discover the basis on which decisions that fundamentally affect their lives and basic rights are made, and have the opportunity to expose corruption.