Defunding statistical agencies poses risks to economies and public knowledge

[Source: U.S. Census Bureau]

[Source: U.S. Census Bureau]

Around the globe, governments defunding statistical agencies has led to staffing decreases and created tough choices for statisticians.

In the United States, a handful of agencies compile official statistics, from the Department of Labor to the Environmental Protection Agency. Most countries have a single agency — commonly called a national statistical office (NSO) — solely responsible for collecting and distributing official statistics.

“Most of the National Statistical Offices, as well as other public administration, are facing regular budget decreases,” Jean-Michel Durr, former France census director, said in an email.

For NSOs, the pressing issue is how budget cuts are implemented, said Durr, who also was the former chief demographer for the United Nations Statistics Division (UNSD), the clearinghouse for global data.

“When it is at a slow pace and well announced, they try to improve their productivity to absorb the diminution of funds,” he wrote. “That is the case in many developed countries. However, in case of a sudden and large cut … it’s more complicated and can lead to suppression of operations (surveys for example or other data collection).”

An Opaque Landscape

The extent to which the U.S. and other western societies have cut operating budgets, trimmed staffs and axed statistical programs is, unfortunately, hard to say. International and U.S. statisticians interviewed for this story weren’t aware of an organization that tracks NSO funding.

The UNSD collects and distributes official statistics provided by NSOs across its 193 member states. The UN division doesn’t track how much countries allocate for statistical agencies, however, nor does it monitor cuts to statistical programs, said Sabine Warschburger, a UNSD statistician.

Representatives of the Open Government Partnership and the World Bank’s statistical office also said their organizations don’t track this information. The International Statistical Institute did not return requests for comment for the story.

In 2013, the UNSD released the results of a questionnaire distributed to national statistical offices. Questions included how satisfied agencies were with government funding.

Of the 126 NSOs that responded, the major sources of unhappiness were “insufficient and decreasing number of staff due to budget cuts” and a lack of funding to train staff. The report didn’t identify how each country answered the questions.

The UN report noted that “the fact that the national statistical office’s budget is decided by parliament or another government ministry will of course have an indirect influence on the work programme and whether all activities in the programme can be implemented.”

When politics threatens public knowledge

According to a 2014 editorial co-written by officials at the U.S. Census Bureau and the Office of Management and Budget, in far too many countries, political influence of official statistics and high-profile cases of state-sponsored “data doctoring” has created “deteriorating public trust in government” and spilled over into the public’s trust of official statistics.

In July 2012, Italy’s chief statistician, Enrico Giovannini, threatened to stop issuing the country’s official statistics in protest to planned budget cuts.

The warning by Giovannini carried a financial cost: By refusing to release key economic data, such as inflation, deficit and job numbers, Italy risked heavy fines from the European Union.

Giovannini didn’t budge.

“Spending cuts are putting (Italy’s statistical agency) Istat at risk,” Giovannini told an Italian newspaper. “The demands are increasing, we are producing more, but our human and budgetary resources are falling.”

The Australian Bureau of Statistics has endured years of substantial budgets cuts, staff layoffs and an embarassing cyber attack that crashed the bureau’s census website for two days. Critics blamed cost-cutting by the government. In March 2017, however, the agency announced another round of layoffs, which the country’s largest public employee union blamed on the government’s “short-sighted and frankly ludicrous budget decisions.”

In the United Kingdom, British researchers documented more than 200 statistical programs that were either “deleted or merged” by U.K. statistical agencies from 2011 to 2012. The data included surveys on adolescent bullying, infant deaths and citizen satisfaction with local government.

Funding problems has not only curtailed data collection in rich countries: it has slowed aid for poorer nations to improving their own statistical capabilities.

Johannes Jütting, head of PARIS21, a global initiative that promotes support and funding for the statistical infrastructure of the developing world, said “heavy budget constraints” by NSOs has manifested into dwindling aid for lower-income countries in desperate need of support.

The UNSD questionnaire, for instance, noted “not a single country in Africa reported to be fully satisfied with the number, skills and experience” of statistical agency staffers.

To date, the integrity of American statistical agencies has not endured sustained scrutiny before committees in Congress or the Trump White House.

Political pressure in other countries, however, has undermined the integrity and independence of statistical work, said Ron Wasserstein, executive director of the American Statistical Association.

“We haven’t had any issues brought to our attention about funding,” Wasserstein said. “But what we have seen are very real threats to the independence of statistical agencies.”

In South Korea, for example, a former presidential administration was accused of pressuring the country’s statistical office to suppress poor economic data until after a reelection bid.

In Argentina, misleading data on the country’s economic health released by the country’s statistical office led to sanctions by the International Monetary Fund.

And in Greece, the country’s systematic manipulation of gross domestic product data contributed to a financial collapse.

The crisis of public trust facing statistical agencies has reached such a low the UN commissioned the so-called “Task Force on the Value of Official Statistics,” whose humble purpose is to remind the public that, yes: data still matters.

The view from American shores

While economists, scientists and labor unions bristled at the White House’s antagonistic view of government-funded research, condemned proposed cuts to statistical agencies this spring and scrambled to archive federal data sets, the budget that U.S. Congress passed in May was not the apocalypse some feared.

Funding mostly increased for the country’s leading research agencies, including the National Science Foundation (up 1.3 percent), the Office of Science (1 percent), the National Institutes of Health (6 percent) and the Agricultural Research Service (2 percent). Even the Environmental Protection Agency escaped the administration’s cross hairs with 99 percent of its prior year budget intact.

The Justice Department, however, received only $89 billion of the $154 billion requested to fund its statistics division. The Labor Department, meanwhile, sought $640 billion in funding for Bureau of Labor Statistics but secured $609 billion, the same as last year.

As is true internationally, fewer resources devoted to statistical agencies has created uncomfortable choices about the kinds of data agencies can afford to collect, said Katherine Wallman, former U.S. chief statistician, in an interview.

What stays and what goes is generally up to the chief statisticians maneuvering budgets, not the invisible hand of political influence, Wallman said.

“It’s really about decisions agencies have to make in the face of budget cuts,” she said.

Whether Congress and the Trump administration is listening remains to be seen. Early signals are troubling.

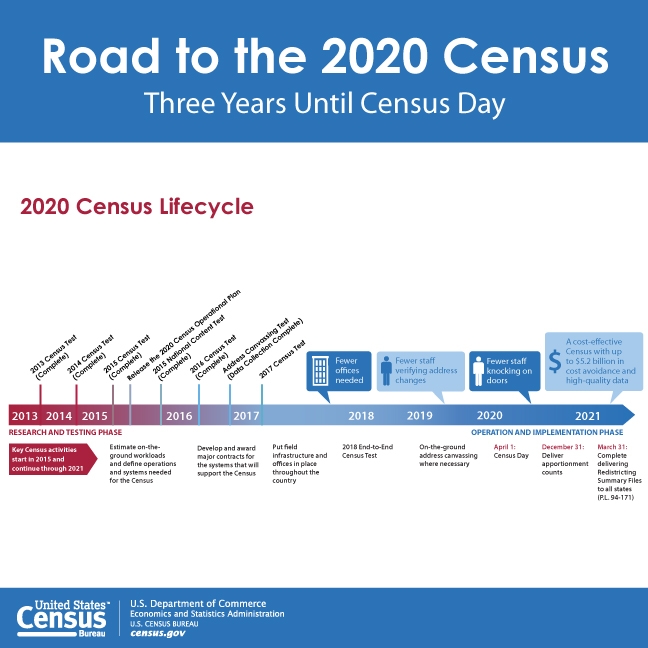

Last spring, the Commerce Department requested $1.63 billion in funding to prepare for the 2020 decennial Census; Congress countered with $1.47 billion in the spending bill Trump signed on May 5.

Four days later, Census Bureau Director John Thompson announced he was resigning in June “to pursue opportunities in the private sector” — presumably at a comfortable distance away from House Republicans and a president unsympathetic to the Bureau’s uncertain future.

On May 23, the White House Office and Management proposed a budget for 2018 that falls short of Obama-era plans for the Census, creating further uncertainty about the future of public knowledge and ability of the American people to know themselves.