Lawmaking is Data-making

With support from What Works Cities and the Sunlight Foundation, cities everywhere are benefiting from public access to open data, data-driven decision-making and service delivery. Opening and using data is reaching all facets of government. New Orleans and Syracuse used prediction models created from national surveys and local data in order to identify high-fire-risk areas and distribute fire alarms. Naperville, Illinois launched a public safety incident map that plots criminal and traffic offenses in order to help residents stay informed about their communities.

One source of valuable data, however, is often overlooked: legal data. Ordinances, regulations, and other law-related materials are one of the most important outputs of government. They not only reflect policy priorities, but they also affect day-to-day government operations and the lives of constituents.

Legal data comes from a variety of sources. The text of the law, for instance, is itself a form of data. It has structural information like sections, page numbers, and links to other laws. And then there’s the substantive content, things like permitting fees, zoning requirements, and tax rates.

Beyond the text, there’s data around when and how the law has changed, along with public interpretive memos issued by city attorneys and secondary sources explaining laws to the general public. There are forms for building permits and business licenses that must be created and updated as new laws are passed.

The ability to access this legal data provides answers to some of the most basic questions. For example, “How did we end up with this law?” – or “What forms will we have to update if we amend this law?” These seemingly straightforward questions are often difficult to answer. Old versions of laws sit on bookshelves or locked in PDFs, the practical equivalent of “gone forever.” There are rarely links connecting forms and the ordinances that affect them.

Connecting different sources of legal data also reduces work for government and improves citizen experience. Governments often rely on separate internal systems for tracking legislative progress, publishing laws, and archiving secondary sources – even though this information is all related. This makes finding information and drawing connections difficult. By sensibly connecting data sources, less effort is required to find information and more time can be spent leveraging it.

What’s the value of converting legal code into computer code?

The benefits of legal data also apply across jurisdictions. Recently, for instance, lawmakers across the country have considered responses to increasing obesity rates. Some have focused on sugary drinks as a potential target. Questions are bound to arise:

- Labels or taxes? Which do citizens prefer?

- What should labels say? What should be taxed and how much?

- What have other jurisdictions done? What was the outcome?

The ability to share and access legal data generated by other jurisdictions trying to answer the same questions provides valuable context and can greatly improve decision making.

Here, however, is the problem. Although the benefits of using legal data are many, capturing legal data is hard.

Most governments publish their documents as unstructured prose on websites or as PDFs. Both of these formats make it difficult for computers to access the information contained within, and the process for making the information usable as data is expensive and error-prone. Once cleaned, normalized, and mapped, the new legal data must then be cross-referenced with other legal data, another expensive and error-prone process. These technical problems aside, publishers often assert copyright over published laws and code, effectively stopping the journey before it begins.

Opening the law in DC

At Open Law Library, we are working with Washington, D.C. to create a platform to overcome these challenges and make capturing and using legal data cheaper and scalable.

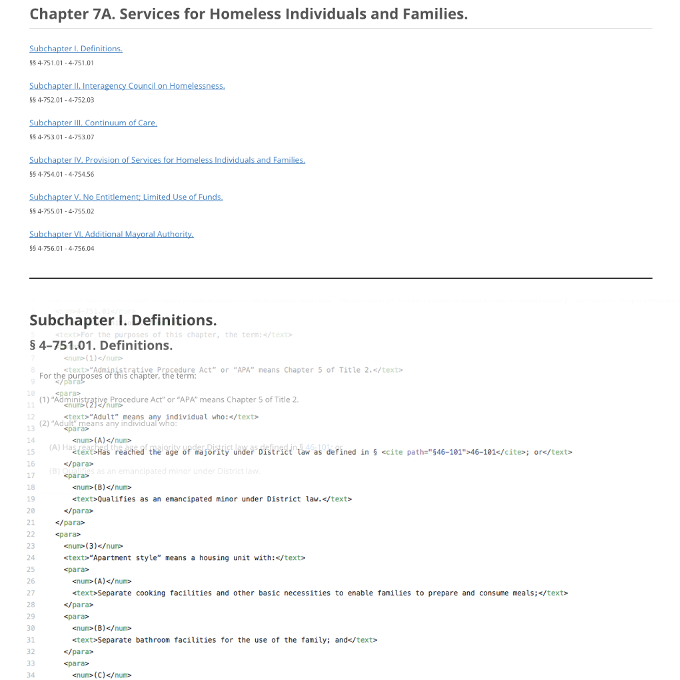

Our platform converts ordinances into computer-readable XML in real-time as the user drafts the law in Microsoft Word. Because the ordinances are in XML, we can automate the process of integrating them into the legal code. What used to take months with a manual process now takes minutes with automation, lowering costs and ensuring legal data is published in a timely manner. We then publish all this legal data as XML on GitHub for public use without restrictive copyright.

We also generate richly annotated and hyperlinked websites by leveraging the metadata, including dates and relationships to other laws, contained in the XML. Our software uses this information to identify relationships among ordinances and code sections and reveal these connections to users.

The D.C. Code that we publish contains, for example, automatically generated history information, making it easy to identify when and how the code has changed and providing direct links to relevant ordinances.

Our platform also provides a robust annotation system, allowing information and links to secondary materials to be published adjacent to the code language. And because the D.C. Code is itself linkable, third parties can easily connect the language of the code to their work.

As we grow this law-as-data infrastructure beyond Washington, D.C. and make more legal data accessible and usable, the benefit to governments and citizens will grow exponentially. New services and tools can be created on top of this aggregated legal data. The quality of laws improves when it is easy to learn what other jurisdictions have done through comprehensive searches. And opening data for the public means creating new avenues for self-service and engagement.

Vincent is co-founder and head of project development at Open Law Library. Open Law Library’s mission is to publish laws and legal data in open, computer-friendly formats for the benefit of governments and the public. You can contact Vincent at vchuang@openlawlib.org.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed by the guest blogger and those providing comments are theirs alone and do not reflect the opinions of the Sunlight Foundation.