Doing data differently – Greensboro’s evolving open data program

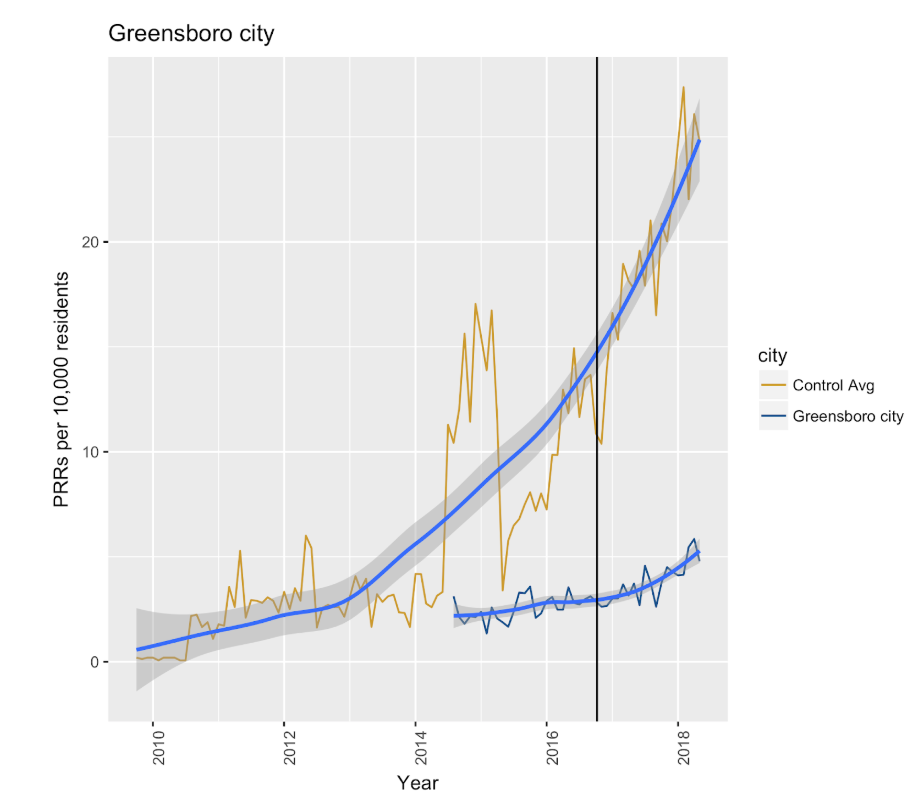

The City of Greensboro, North Carolina used public requests for information to help build an open data portal that was responding directly to residents’ needs. The City took a resident-informed approach to open data, and as a result, has seen public records requests drop off in comparison to national trends.

This phenomenon is in line with an important early discovery in our recent paper on the relationship between open data and public records requests (PRRs). We found that adopting an open data policy reduces the number of PRRs cities receive on a monthly basis in cities across the country. Based on Greensboro’s success and the trends in other cities rolling out open data, we believe that cities need to publish datasets that are of high interest to citizens to get the benefits of open data and see a decrease in PRRs.

In 2017, Sunlight Foundation’s Open Cities team worked directly with the City of Greensboro to write an open data policy and launch a data portal called “Open Gate City,” providing data to facilitate transparency, promote community engagement, and stimulate innovation.

Greensboro has built a critical foundation for using data and evidence to deliver improved results for residents. But how can other cities apply lessons from Greensboro to ensure their burgeoning open data programs are designed to best meet the needs of community residents? Using PRRs and feedback from residents to guide open data priorities is an important mechanism in ensuring the programs efficacy – cities should remember that open data is only worthwhile when residents can make use of it.

A year on, we followed up with Jane Nickles, CIO of Information Technology Department in the City of Greensboro to learn more about their experience with open data and PRRs:

SF: What motivated the city of Greensboro to pass an open data policy?

JN: It was the Bloomberg What Works Cities program that initially caught our attention; that’s when we began learning about open data. We applied and were accepted into What Works Cities, and their support helped us to launch our first open data program, along with the performance management program.

Initially, we lacked support from city leadership, but Sunlight Foundation’s Open Cities team presented the case for open data as a tool to improve efficiency and promote engagement with residents, which generated a lot of interest.

SF: Talk us through the decision to develop the Open Gate City open data portal.

JN: In creating an open data policy, our vision was to have an open data portal and to use it to engage the community and our internal departments. We wanted to have a repository to store data, knowing there could be multiple uses for the data, and that a portal could to meet internal and external needs concurrently.

While we’re not totally there yet, a comprehensive portal is still the ultimate goal. Our dedication to maintaining an open data portal was somewhat complicated by the fact that we lacked a dedicated resource for the program. But we’re making progress in convincing others of the value of these programs, and the portal’s success speaks for itself. I hope we’re close to gaining a dedicated resource for Greensboro’s open data work.

Figure 1: Trend in PRRs per 10,000 Residents in Greensboro, NC

SF: Greensboro was one of the cities in our study that had significantly fewer PRRs after passing an open data policy. Do you consider PRRs as a measure of citizen demand? Do you use them to decide what to release via the open data portal?

JN: We do look at PRRs – in fact, we used PRR data to determine what we’d release first on the open data portal. We worked closely with the department handling public records requests and accessed a list of the top ten data requests from residents – that was where we started when releasing data.

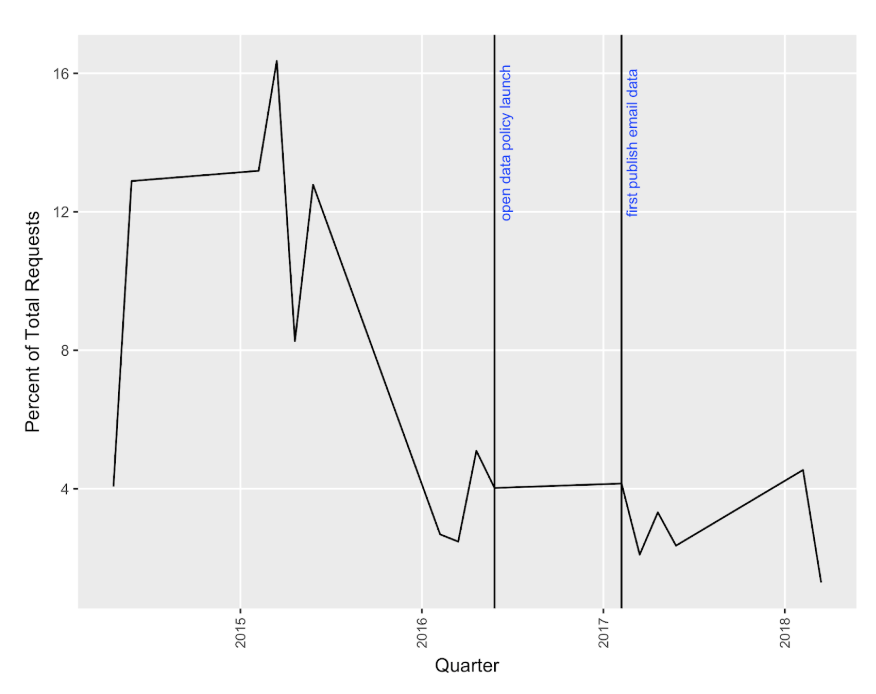

One of the more innovative things we did was to put city council members email on the open data portal. Automating this process with the open data portal has really helped with efficiency; once emails are reviewed [and any confidential information is redacted], they’re automatically posted to the portal.

SF: What has been the effect on public records requests following the launch of the open data portal?

JN: Given our strategy of prioritizing publication of data most requested by residents, I would assume the volume of PRRs would decrease. We’ve seen other impacts from the portal, particularly in regards to efficiency in how we do work.

Figure 2: Percent Quarterly Requests for City Emails, Social Media Posts Over Time

SF: How did the city generate community interest in and promote use of the city’s open data portal?

JN: We did a launch event at HQ Greensboro, an entrepreneur coworking space downtown. We invited the community to attend our hackathon, and challenged folks to make use of the newly published data. People came up with all sorts of interesting things. Someone created a heat map of fire incidents, complete with accompanying times of when fires happened. Another participant did research on food deserts, creating a tool for finding the closest grocery stores or food bank. It was a successful event with a great turnout – it really helped us gain interest and build community.

SF: What are your goals for the Open Data Program in the next year?

JN: We want to tell our story as a city with data. It would be immensely valuable to have a comprehensive dashboard where folks can see what’s happening in Greensboro and why; residents would be able to better understand city priorities. We can build trust with residents by providing this data and acknowledging what we could be doing better, and how we’re trying to do better. Residents can use data to monitor the work and hold us to account – we’re also ramping up performance metrics on the portal so we can better understand how it’s being used by folks.

In the next year we’ll strive to have a dedicated resource to really validate the program and take our work to the next level – it’s something we’re committed to.

Note: Interview has been edited for clarity and length.