Research: Cities can save time on records requests by doing open data right

Adopting an open data policy significantly reduces the number of public record requests that cities receive compared to cities that lack an open data policy. This was the major finding of a study I set out to conduct earlier this summer, to understand the relationship between the growth of open data policies and longstanding freedom of information laws. I found that while the average number of public records requests cities receive is growing significantly over time, cities could save time and money by passing an open data policy and investing in a robust open data program.

As a result of my research, I can say confidently that city officials should allocate resources to passing open data policies and building robust data portals in the face of a nationally increasing volume of public records requests. Access to information is a fundamental democratic right, and given that the benefits of providing proactive access to information brings positive benefits back to cities, it is clear that city officials should be proactively releasing open data that belongs in the public domain.

My initial research questions asked whether FOI and open data are siblings or silos. Through its work with cities across the U.S., Sunlight’s Open Cities team has heard definitively that cities with limited resources effectively wanted to provide citizens with timely and comprehensive access to public information. To do that, cities would have to understand the relationship between these two channels of public information.

To conduct this research, I collected 236,616 historical public record requests (PRRs) from 52 mid-sized cities across the US, dating back to October 2009. I analyzed whether adopting an open data policy significantly affected the number of monthly PRRs cities received and whether the robustness of a city’s open data program impacted the results. I also analyzed the text of 110,063 PRRs from the 33 cities in our sample that publish this information to understand what types of information are most commonly requested by citizens, and whether this changes when cities adopt an open data program.

Finding #1: Adopting an open data policy reduces the number of PRRs that cities receive

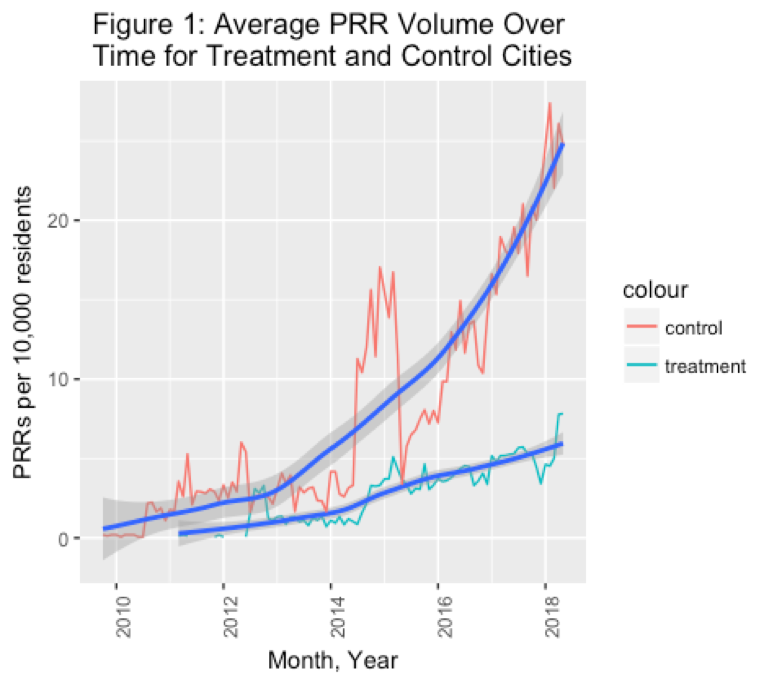

An important early discovery in our study of PRRs was that the number of PRRs cities receive is generally increasing over time. Average PRR volume has increased from approximately 33 requests per month in 2011 to 188 per month in 2018. While I don’t yet know the cause of this increase, I found that adopting an open data policy caused approximately a 30% decrease in the number of PRRs per month as compared to the control group. In other words, adopting a policy of proactive disclosure of public information appears to be one of the best ways for cities to effectively respond to growing demand for public information. While the sample of cities in our study is not randomly selected, the variety of cities included (covering 14 states across the United States and ranging in population from 18,749 to 850,282) indicates that these findings have broad applicability across different types of cities. To further verify the robustness of our findings, I used statistical methods to control for the differences between cities that adopt an open data policy and those that do not which confirmed our results.

Finding #2: Cities that adopt a more robust open data program see a greater reduction in PRRs.

In evaluating cities’ open data programs, I wanted to include a measure for quality of open data to determine whether cities that implement a more comprehensive open data program experience a greater reduction in PRR volume. Comprehensiveness of an open data program exists in two dimensions: first, whether the city’s open data policy is robust, which I define as compliant with the majority of the Sunlight Foundation open data policy guidelines, and second, whether the city’s open data portal is robust, which I define as hosting three of the most highly demanded open datasets (crime, budget, and spending).

Incorporating these quality measures into our model, I found that adopting an open data portal alone does not cause a significant reduction in the PRR volume, but implementing a robust open data portal decreases volume by 33 percent compared to the control group. Adopting a robust open data policy has the largest statistically significant effect on PRR volume, decreasing monthly PRRs per 10,000 residents by 43%, as compared to the control group. These findings confirm best practices in the field of open data: data that’s released should be aligned with community demand. Cities can identify demanded data sets by looking to analysis of popular datasets in other cities or adapting the methodology outlined in our white paper to analyze what types of information citizens request via PRR. Launching an open data portal will only affect the volume of PRRs once the city has invested in releasing sufficient data on the portal to displace the need for some PRRs.

Finding #3: Patience is important when evaluating the effect of an open data program.

I analyzed whether the effect of adopting an open data policy changes over time and found that the effect grows each year. For example, when I look at the differences in the effect of adopting an open data policy on PRR volume between 2015-2018, I found that the magnitude of the effect grew each year and that the marginal effect in 2018 was twice as large as in 2017. In fact, the effect only became statistically significant in 2018.

I also found that for each additional month an open data policy is in place, a city can expect to receive 4 fewer PRRs than the month before compared to the control group, holding all else equal. This shows clear evidence of a maturation effect of open data programs. It takes time for citizens to change their behavior to use open data resources. This maturation may be the result of deliberate and critical efforts by cities to grow their open data programs by publishing more open data, conducting outreach, and engaging citizens around the use of open data.

Our analysis also revealed several areas that merit further investigation – such as how adopting an open data program affects who submits requests and how long it takes cities to respond. I encourage future researchers to read the full report, email us at opencities@sunlightfoundation.com, and build on our efforts and answer important questions about how cities can make open data effective and impactful.