Transparency can help transit agencies earn public trust

Transit agencies have shown they can be outstanding publishers of open data. Openly publishing schedule data (and, increasingly, real-time location data) has become the norm, and the standard used for transit schedule data is one of the nation’s brightest open data successes.

But what about information about transit agencies themselves — topics like budgets, spending, costs, ridership, procurement, and union contracts? Some of this information is difficult to find (because it’s buried in large PDFs, for example) while parts may not be public at all.

A number of transit agencies face crises of public confidence, and greater transparency can help address this. Additionally, it can help build productive relationships with advocacy groups and enable their work. It’s particularly important to spotlight transit agencies because many have not made the types of commitments that city and county governments have.

Restoring public confidence

A number of U.S. transit agencies face a crisis of public confidence, with widespread public skepticism about their management — especially in the face of declining service quality and safety problems.

This has led passengers and legislators to question whether the systems can be trusted with more investment — a sentiment that may exacerbate cycles of declining ridership and repair needs. This is a particularly salient issue in systems that have had high construction costs yet are also seeking additional funding for infrastructure renewal.

Credit: MTA Capital Construction / Rehema Trimiew

Construction costs for New York’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) offer an example. As the New York Times reported in 2017 (and some have noted for years), the MTA routinely pays as much as seven times as much per mile as comparable projects elsewhere in the world. According to the Times, the MTA discovered in 2010 that it was paying about $200,000 per day for some reason that no one could figure out; this was not disclosed to the public.

These kind of stories understandably make the public weary about whether or not transit agencies are spending their money wisely. This matters when agencies are trying to make the case for increased funding at a time when government budgets are often strained.

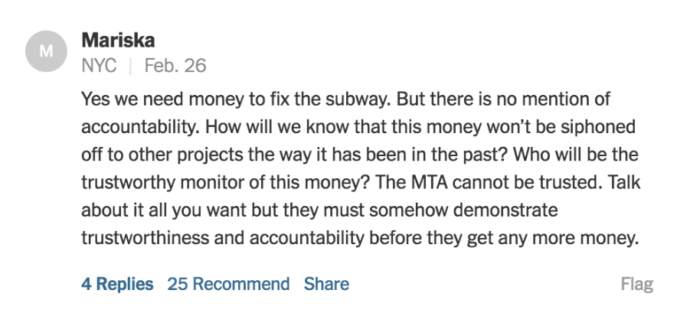

New York’s proposal for charging drivers entering Downtown and Midtown Manhattan (to help raise money for transit) faces questions like this:

Comment on a New York Times article about congestion pricing

If agencies seeking additional money want the public and politicians to get onboard, they would be wise to embrace significant increases in transparency — most obviously around finances, but also on other topics like performance and ridership.

Enabling advocacy and productive relationships

The end goal of most transit advocates is to improve public transportation. Assuming that the transit agencies’ leaders share that goal, they should want to have a productive and collaborative relationship with advocates.

Open data about transit agencies is crucial for transit advocates. Whether calling for funding for needed maintenance and repairs, analyzing ridership trends, or weighing-in on service alternatives, advocates and their arguments benefit from access to the same facts and figures that government officials have.

Even if advocacy groups and agency leaders sometimes disagree about specific courses of action, proactively providing information to the public at least demonstrates good faith on agency leaders’ part, and can help improve agencies’ relationships with the public.

A redesign of the bus network in Baltimore led to questions about how the local transit agency was measuring performance. Baltimore transit advocate Danielle Sweeney writes that she was only able to get route-by-route performance data after months of making public-records requests. That’s absurd. This type of refusal to be open breeds public mistrust of agency leaders’ intentions.

Credit: Wikimedia Commons / Griffin5

Catching up with other local governments

Plenty of local governments have passed policies about open data, yet few transit agencies — which are usually separate from city and county governments — have made similar commitments. It’s time to hold transit agencies to the same standards.

Transit agencies also often suffer from a lack of accountability due to complex governance structures. It is often unclear who transit agencies are accountable to. Many are governed by boards whose members are appointed by multiple elected officials. It can be easy for transit officials to pass the blame to others, and difficult for voters to “have their say” on transit issues. For these reasons, it’s especially important for transit agencies to embrace the highest standards for transparency.

We’re excited by the rise of open government data and transparency in local governments around the country. The benefits of doing this apply to transit agencies as well, so we’d love to see them get on board. (Pun intended!)