Think that Minute Details on Federal Government Websites Don’t Matter? Think Again.

Did loose grammar on a Federal Trade Commission webpage raise and then dash the hopes of millions?

In 2016, the Office of Management and Budget admitted that federal agency websites “are the primary means by which the public receives information from and interacts with the Federal Government.” If you had any lingering doubts about the importance of information on federal government websites, the events of the last week relating to the Equifax data breach settlement — the excitement that quickly turned to disillusionment — should well and truly dispel them.

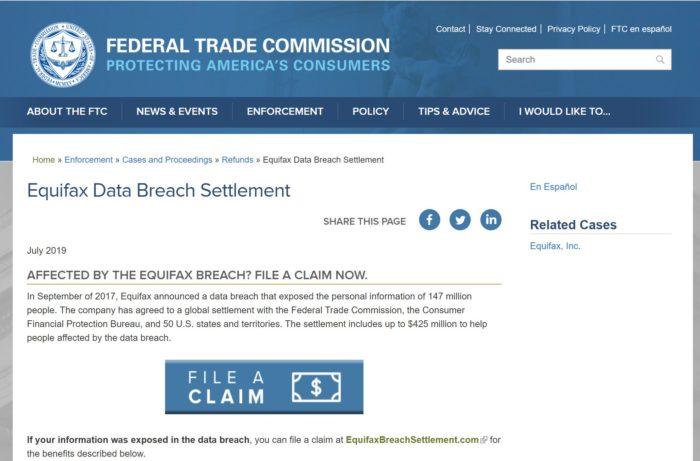

As we detail in our latest report, on July 22, 2019, Equifax settled with the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) for a 2017 data breach, which exposed the private information of close to 150 million people. That same day, the FTC published a webpage that explained individuals affected by the breach could “[o]nce the claims process begins … request… Up to 10 years of free credit monitoring OR $125 if you decide not to enroll because you already have credit monitoring.”

“Up to 10 years of free credit monitoring,” the page said. Up to 10 years. Hmmm… OK. But, $125 cash! Woo hoo!

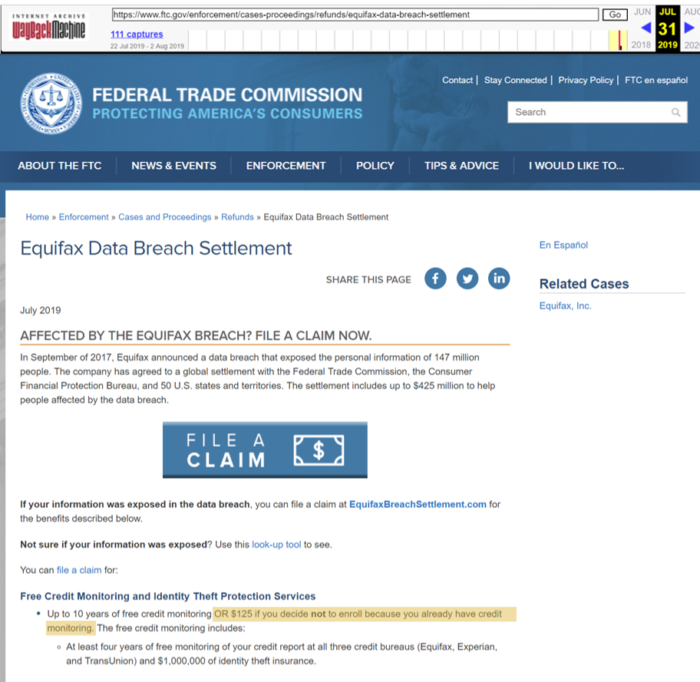

Nowhere did the webpage mention that the cash payments were capped at a maximum of $125 and that, no matter how many of the 147 million potential claimants came forward to claim their cash, only $31 million would be divided between them.

The top portion of the “Equifax Data Breach Settlement” page as captured by the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine on July 31, 2019 at 11:02:43 AM ET, highlighting the text that raised hopes about a cash payment of $125.

It didn’t take long for the internet to go wild with the news of a free $125 for half of the US population. CNBC went with the headline, “I may have banked up to $125 by filling out this Equifax claim in seconds — What are you waiting for?” The Verge reported “Equifax owes you a lot more, but here’s how to get $125 from this week’s settlement,” explaining that you could opt for either “a $125 check or pre-paid card”. Elated and irreverent tweets like this one from @Julian_Epp proliferated Twitter. Even social-media savvy AOC got in on the game, declaring that everyone should “go get your check” (before issuing a clarification that the 10 years of free credit monitoring is the better deal).

Me and the boys spending the $125 we got from the Equifax data breach pic.twitter.com/jdP0l9iShH

— Jules (@Julian_Epp) July 27, 2019

Like many others, I too was pleased when I first read the news of the settlement on my phone while waiting to pick up a rental car. One of the adjustments I’ve had to make moving to the United States was the ease with which private companies acquired, retained, and distributed my private information. (Other countries protect private data from corporate interests to the same extent that the US restricts government use and sharing of its citizens’ personal information.) The annoyance at having my personal information bought and sold without my consent — and then leaked — notwithstanding, I thought to myself, “Hey, a free $125! I better get on that.” But I was trekking over from San Francisco to rural California, where I would be without internet (gasp!) for several days. By the time I returned to the interwebs, elation and cheer had given way to cynicism and disappointment. I still haven’t submitted my claim.

What had happened during my webcation?

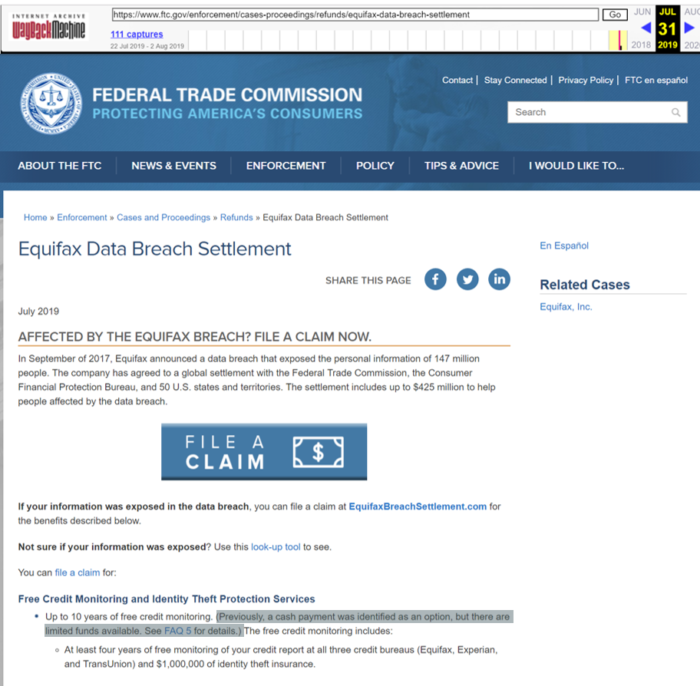

The FTC issued a press release, blog post, and updated the Equifax data breach settlement webpage on July 31 to dissuade affected consumers from claiming the $125 payment, explaining that:

“Because the total amount available for these … payments is $31 million, each person who takes the money option is going to get a very small amount. Nowhere near the $125 they could have gotten if there hadn’t been such an enormous number of claims filed.”

So many people claimed $125 from the Equifax data-breach settlement that there’s no money left to get anything. Equifax only set aside $31 million for 147 million affected people which is just 21 cents per person. Only 248,000 people could have claimed $125.

What a rotten scam.

— Eugene Gu, MD (@eugenegu) August 1, 2019

The media had also done the math, as it were, and figured out that $31 million divided by $125 was 248,000 — not 147 million. Correctives were issued. The Washington Post led with the headline ‘Did someone forget to do the math?’ Consumers, advocates rail against lowered Equifax cash payouts.” Market Watch referenced the FTC’s backtracking: “Sorry, you’re not getting $125 from the Equifax settlement, FTC says.” Many people, like those in this Twitter thread, were left disappointed and jaded.

The top portion of the “Equifax Data Breach Settlement” page as captured by the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine on July 31, 2019 at 3:30:42 PM ET , highlighting the text that recanted the $125 cash payment option.

None of this is to say the FTC did an especially bad job in communicating to the public. Certainly, they could have been more thorough (mentioning the $31 million cap) and chosen clearer grammar (emphasizing the “up to” as it related to the $125). They did help create the expectation that all affected people were going to get $125, which itself is a pretty small amount to compensate for a lifetime of concern about identity theft.

However, to be fair to the FTC, settlement agreements are complicated, and there was a good deal of urgency to publish information about the settlement immediately after it was finalized. It should be noted that the FTC weren’t the only ones to make the mistake: the website run by the Equifax settlement administrator, https://www.equifaxbreachsettlement.com, repeated the mistake, as this capture from the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine reveals. Similarly, many journalists, who should be well versed in fact-checking and primary sources, repeated the $125 figure without caveats.

The $125 figure did come straight from the settlement agreement, the only thing that was missed was the latter part of clause 7.5 (on the 21st page of the 294-page agreement) that explained that if payments “exceed the cap set forth in the preceding sentence, then payments … shall be distributed pro rata to those making valid claims.” The cap set forth in the preceding sentence was $31 million.

The broader point here is that what is on government websites matters. The Equifax case highlights the extent to which inaccurate, incomplete, or even slightly misleading information has real consequences. People assume — justifiably — that information on government websites is reliable and act on that information. Millions of people. And the natural response when such an assumption is proved wrong is disappointment, distrust, and disaffection.