Why Kenya’s open data portal is failing – and why it can still succeed

Kenya’s open data portal is floundering. Despite the excitement that surrounded its launch in July 2011, the portal has not been updated in eight months, has seen stagnant traffic, and is quickly losing its status as the symbolic leader of open government in Africa.

For a number of reasons, the portal, which runs on a Socrata platform and can be viewed here, has not lived up to the often sky-high expectations of many onlookers.

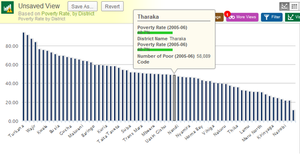

A screenshot of Kenya’s open data portal

First, government ministries have been reluctant to release data. Many observers expected that the launch of the portal would help eradicate the Kenyan government’s harmful culture of secrecy. The Official Secrets Act, a holdover from the colonial era that prevents government employees from sharing official information, has created a closed culture in government and has starved the portal of much needed information.

Second, implementation of the new constitution has hamstrung government officials who are trying to adjust to new roles and identify new responsibilities, significantly reducing government officials’ ability to incorporate open data into their already overburdened workstreams. The new Kenyan constitution, which was overwhelmingly passed in a 2010 referendum, created a new devolved system of government. Large changes are still being implemented, and government officials are struggling to adjust.

This inexhaustive list displays some of the large obstacles standing between the open data portal and the goals of a more transparent, accountable, and effective government. Despite these challenges, there is still hope that Kenya’s open data experiment can regain its footing and reestablish itself as an open government leader.

First, a bit of history. Jay Bhalla, executive director of the Open Institute and a member of the Open Data Task Force that developed Kenya’s portal, argues that the Task Force “ran before it could walk.” The task force was organized by Bitange Ndemo, the former Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of Information and Communication, and was made up of computer programmers, data experts, legal experts, Statistics Bureau employees, and individuals from the World Bank, all of whom were volunteering their time to push the government to develop an open data portal. Once President Kibaki approved the idea, the team hurriedly developed the portal, gathered the data, and did their necessary legal and policy homework. Remarkably, the portal was launched a few weeks after gaining approval from President Kibaki.

The implementation of the new constitution and the massive elections held earlier this spring have shifted priorities away from open data. However, early signals suggest that new President Uhuru Kenyatta is amenable to the idea of open government data and greater transparency. In May, Kenya hosted the Open Government Partnership Africa Regional Meeting, where the ICT Cabinet Secretary spoke optimistically about the prospects for open government in Kenya.

Rhetorically, open government is easy; however, according to Bhalla, some more concrete steps are being taken by the new government to improve the open data portal. There have been initial discussions about starting an inclusive task force that would bring together government, civil society, and media to work towards improving the portal and ensuring its usefulness and relevance. Inclusive processes that bring together all major stakeholders can generate the energy, buy-in and consensus needed to move the portal forward.

A more open legal framework is also critical to the portal’s success. The lack of a freedom of information law has made it difficult to get government institutions to release information and has weakened the standing of pro-openness organizations and individuals. This, too, might be changing. The new constitution recognizes an individual’s right to information. While the legislature still needs to develop a framework to implement and codify this new constitutional right, discussions have been ongoing in the parliament and there appears to be a good a deal of momentum behind a freedom of information act. This is a promising development for the future of open government data in Kenya.

The changes to government brought about by the 2010 constitution also provide the space within which new ideas can thrive. The devolved county system creates 47 new sub-national political units that are, to some degree, starting from scratch. Training new officials, creating new public institutions, and developing new government processes provides space for open data to be incorporated into the daily work of governance.

For example, the International Budget Partnership and Kenya’s National Taxpayer’s Association are capitalizing on the opportunity presented by devolution to train new counties in participatory budgeting, an innovative practice where citizens play a central role in public sector budgeting. The program, which was piloted in 5 counties and has quickly grown to 12, has been highly successful, due in part to the interest of local officials and leaders. As the article attests, the process of devolution has provided the space for innovative budgeting practices to become reality. The same can — and should — be true for open government data.

Outside of government, efforts by civil society to strengthen the open government data space are also encouraging. Two noteworthy examples are Data Bootcamp and Code for Kenya. Data Bootcamp is an effort to provide training to journalists and civil society organizations interested in using open government data. Piloted in Kenya, Data Bootcamp has since moved to several other countries, most recently Malawi and Ghana. Code for Kenya places fellows, who are computer or data experts, in media and civil society organizations to improve the hosts use and understanding of open government data in Kenya. These civil society efforts are encouraging, as buy-in and participation by civil society is necessary for open government data to be meaningful and relevant.

Another cause for optimism is that the Kenyan open data portal has been a catalyst for regional activity on open data. Ghana, Rwanda, and Tunisia have all taken steps to open up government data and the Kenyan Open Data Task Force has been contacted for guidance by officials in Uganda, Tanzania, and Nigeria. Some of these countries have even launched their own data portals following Kenya’s example: Tunisia launched a beta version of its own open government data portal, Edo State in Nigeria recently launched an open data portal, and Africa Open Data was launched, a platform hosting data from all countries on the continent. As Kenya’s portal becomes stronger and more relevant, we expect it to continue to motivate countries and civil society organizations around the region to open up and engage with government data.

All this points towards a resurgence in the use and value of Kenya’s open government data portal. The portal has not been without its problems — limited government buy in and a weak legal framework to name a few — but there is cause for optimism.

Thanks to Jay Bhalla for his assistance on this post.

This post was prescheduled to be published on September 23. Given the horrific events in Nairobi that week, we removed the post and intended to republish it at a later date. The post was republished two weeks later on October 9.