Sunlight’s review of federal open data catalogs (Hint: It’s not so great)

We at Sunlight are conducting a broad audit of agencies’ sometimes-faithful attempts to comply with President Obama’s open data executive order from 2013. Our findings so far are good, bad and perplexing.

It’s no secret that finding machine-readable government data can be difficult. At Sunlight, when necessary, we pursue lawsuits and legislation just to get to good data. However, there are some things we just can’t do. While auditing the Department of the Interior’s data catalog, we were left scratching our heads. Too often with federal agencies the data is missing, but with Interior, sometimes we know exactly where it is – there’s just no way for us to touch it. For instance, how are we supposed to get hold of file://LISA-PCC$UsersLisaDocumentsWorking Folderbackup_master1_2PADUS1_2_23Feb2011.gdb?

Some background

The executive order requires federal agencies to publish more and more of their information online, and an important component to this is ensuring that the information is published in a way that is useful to the public. This means, for instance, creating indexes about what data is available, prioritizing important data, and releasing it in machine-readable formats.

One of the most basic requirements is that the index of data actually directs a viewer to the data – for instance, through a hyperlink. In instances like the above, someone – presumably Lisa – has only told the world where to find the “PADUS1_2_23Feb2011.gdb” database on her own computer. It is of no use to the rest of the Internet. Is it somewhere else online? Is it useful data? What does the geodatabase map do? There’s no way to know.

OMB’s dashboard

Fortunately, we’re not the only ones looking for these lapses. So, too, is the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), the agency charged with helping agencies’ data policies stumble into the 21st Century. OMB isn’t perfect – and has achieved some inglorious feats, such as releasing only one Open Government Plan. They aren’t required to produce these plans, but are charged with making sure other agencies do (those agencies that must comply are supposed to be on their third).

But for the task of reviewing agencies’ compliance with the executive order, it’s doing an admirable job so far. Such a good job, in fact, that we’re hoping it will change OMB’s complicated reputation within the open data advocacy sphere.

OMB’s attempt at analyzing compliance is strong, and much of their analysis is public. This post isn’t about every way in which it could be improved; though, to highlight an example, the published information about agencies’ Enterprise Data Inventories is limited to a red/yellow/green system, meaning many details (like the size of the inventories and the reasons why an agency has decided not to release certain data) are inaccessible.

As Sunlight began our own audit, we took note of how shallow OMB’s analysis currently is. Its analysis tracks some hard numbers and some qualitative issues, things like percentage of datasets with valid metadata and “Public Engagement.” But it stops short of checking whether the data was linked to, whether the link was a valid URL, whether that URL actually worked and whether the dataset it linked to was machine-readable.

Sunlight’s audit

So we embarked on our own audit to show that it was possible and important to take these extra steps. We looked to agencies’ public data listings – the public, sterilized versions of Enterprise Data Inventories, effectively catalogs of downloadable datasets.

Project Open Data — a repository of tools, schemas and best practices — spells out the requirements for compliance with the executive order. The public data listings were supposed to be available by Nov. 30, 2013, with a machine-readable file at “www.[agency].gov/data.json.” We started by taking a look at a selection of agencies’ data.json files to see what was available and what data formats the agencies were publishing.

The process

We wanted to confirm:

- whether the data.json catalogs for federal agencies exist where they are supposed to (we looked at 38 agencies, not all of which are legally bound to follow the executive order);

- whether those catalogs are valid JSON; and

- whether the various URLs listed therein point to downloadable datasets.

According to the schema, agencies have the option of listing a single or multiple URLs for a single dataset, as well as a URL for a webService if the dataset has an API. We collected all of the URLs that might point to a downloadable dataset or API and performed a HTTP HEAD request, which asks for information about a resource at a URL without actually downloading the content.

Step 3 is where we found the most interesting results. Valid web URLs – a pretty low standard to which one might hold any data catalog – proved to be a challenge for the federal government. Sometimes instead of an accessURL there is a short message in place of a URL or an identifier for a non-web resource. While examining the public data catalogs we found multiple entries that point to files on people’s PCs or internal servers. Enter: Lisa.

Anecdotal results

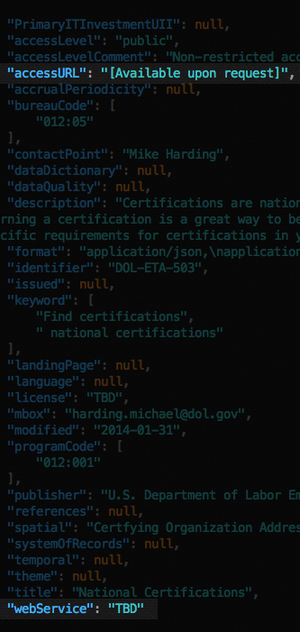

Having both a machine-readable catalog and URLs pointing to downloadable data can facilitate the process of harvesting and processing data from government agencies. Invalid URLs, such as the one pointing to Lisa’s PC or ones that aren’t URLs but messages such as “TBD” or “[Available upon request],” aren’t useful.

Even after we corrected URLs that were missing an http or https, we still found instances of completely invalid URLs. We saw typos, invalid domain names and other oddities.The departments of the Interior and Labor had many issues, but a number of issues cropped up elsewhere.

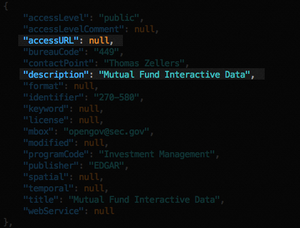

The Securities and Exchange Commission identifies 47 public datasets in their data catalog but does not provide URLs for any of them. One dataset is identified as “Mutual Fund Interactive Data,” while the others are various forms or “rules.”

Some agencies didn’t have a data.json catalog file at the required URL. Try http://www.fcc.gov/data.json for example – it redirects you to fcc.gov/data – a fine solution for human readers, but something that both disobeys the implementation guidance and breaks scripts. Some had a catalog file at the proper location but it wasn’t valid JSON or didn’t conform to the Project Open Data schema.

Our most compelling results so far, with more comprehensive analysis, are the subject of a subsequent post going up tomorrow and will be the focus of a series of follow-up, in-depth explorations.

Sunlight reaches out to OMB

With the results we found, Sunlight reached out to OMB. We wanted to do so before its own compliance check (which is an ongoing process) was updated; while it’s nice to throw spitballs at people for underperformance after the race is over, it’s much more productive to let them know where their blind spots are before they cross the finish line. The response we received bolstered our hope, as noted above, for OMB.

We’ve since been working with the Project Open Data team and various other federal employees that are working to evaluate and develop agencies’ data metrics. After showing them our initial findings, we’re happy to say that they have started to expand the capabilities of their dashboard. Right now, that means adding their own checks on URLs in the public data listings and checking for content type. Meanwhile, we’ll be doing deep dives into compliance agency-by-agency, seeing what else needs to be built into that analysis — and what other gems lie waiting to be found, announced and fixed. First up are the departments of Defense and Interior – check back in tomorrow to get a look.