Stop and frisk in 4 cities: The importance of open police data

In 1968, the U.S. Supreme Court addressed the constitutionality of police searches for weapons without probable cause for arrest under the Fourth Amendment. This decision, Terry v. Ohio, held that a limited search for weapons is permitted when an officer reasonably suspects that the stopped person could be armed. Generally, it established the constitutional practice of what we know as stop and frisk, or Terry stops, by police officers.

In recent years, data collected during Terry stops has shown that some police departments have misused the practice and, in doing so, violated the constitutional rights of some citizens. The practice’s misuse has been attributed to department stop quotas which forced police officers to increase the number of stops they conduct. The increase in stops affected some racial groups more than others, highlighting racial bias in policing.

In some cities where stop and frisk is practiced, collected data has led to more accountability for both officers and departments. However, in cities where stop and frisk data is not collected, it’s impossible to assess the lawfulness of the practice or hold police accountable. Police departments in New York, Philadelphia, Los Angeles and Chicago all practice stop and frisk, but some do better than others in making the data collected available to the public and in an accessible format.

The state of stop and frisk

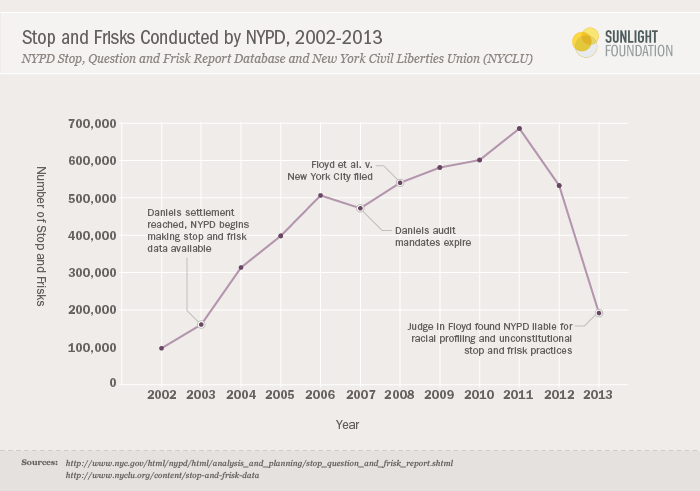

New York serves as the landmark example for how the release of police accountability data can affect the practices of a police department. Public and widespread issue with stop and frisk practices first emerged in New York in the 1990s during the broken windows era of policing. A class action lawsuit challenged constitutionality of stop and frisk practices of the New York Police Department (NYPD) under the Fourth and 14th Amendments: It held they were conducting Terry stops without reasonable suspicion and with racial bias.

The 1999 class action lawsuit, Daniels, et al. v. The City of New York, addressed racial profiling and unlawful stop and frisks performed by the department. Among other requirements, the court ruled that the NYPD provide data to the plaintiff, the Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR), to conduct quarterly audits of NYPD stop and frisk practices through 2007. After noncompliance with the court’s ruling and a continued increase in stop and frisk events, the CCR filed another class action lawsuit against the NYPD in 2008, Floyd et al. v. City of New York. Rulings consequent of Floyd held that the NYPD must continue to make stop and frisk data publicly available.

Since 2011, data shows that the NYPD has dramatically decreased their unlawful stop and frisk practices, both in excessive use and racial bias. Data released on Monday continues to show this trend. The NYPD conducted 46,235 stops in 2014, approximately a quarter of the stops conducted in 2013.

Similar to New York City, Philadelphia made stop and frisk data available in result of class action lawsuits that arose from the observation of excessive and unlawful police stops. The Philadelphia Chapter of the ACLU of Pennsylvania (ACLU-PA) has been integral in advocating for the regular publication and analysis of Philadelphia Police Department (PPD) stop and frisk data. The 2011 case of Bailey v. City of Philadelphia alleged that the PPD was conducting stops on the basis of race, thus violating the Fourteenth Amendment. The court ruled that the PPD implement an electronic database to collect more detailed and analyzable stop and frisk data. This electronic database was implemented in January 2014. On Feb. 24, the ACLU-PA released its fifth court-mandated report concluding that the data still reflects high levels of unlawful stops, with 39 percent of stop and frisks being conducted without reasonable suspicion. Previous reports have shown that the excessive and unlawful practice of stop and frisk has improved in recent years; data from 2011 showed that 50 percent of stop and frisks were conducted without reasonable suspicion. Despite this decline in unlawful stop and frisks, ACLU-PA continues to threaten further legal action and calls for greater accountability measures for the PPD: “Without strong accountability measures, the high level of violations of constitutional rights will likely continue.”

Litigation in Philadelphia required the collection of usable data and promoted accountability of the PPD, thus reducing misuse of stop and frisk. But, as highlighted by ACLU-PA, the misuse is still present in Philadelphia, and future litigation may be pursued if “substantial improvements” to the practice are not made soon.

The Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) experienced widespread police reform after what became known as the Rampart Scandal in the late 1990s. The Rampart Scandal resulted from widespread corruption in the LAPD’s Rampart Division, a specialized anti-gang unit, including unsolicited shootings and beatings by officers. In 2001, the U.S. Department of Justice put the LAPD under a consent decree mandating the collection of field data reports and an independent review of stop and frisk data. This review of stop and frisk data was completed in 2006. The report concluded that there was no statistically significant evidence of racial profiling by the LAPD, but that in some police bureaus there was a significant trend of Hispanics and blacks being more likely to be subject to a frisk than other racial groups.

Today, the LAPD no longer collects data on pedestrian stops despite extensive reforms implemented from 2001-2009, the years the department was subject to the consent decree. In Los Angeles, without the need to produce stop and frisk data, the ability to hold the LAPD accountable is diminishing.

Chicago has also had issue with excessive and racially-based Terry stops that emerged in the mid-1990s from the Chicago Police Department’s “gang-loitering ordinance” (which contributed to high levels of arrests). The U.S. Supreme Court struck down the ordinance in Chicago v. Morales (1999) with evidence of it supporting an “arbitrary restriction on personal liberties.”

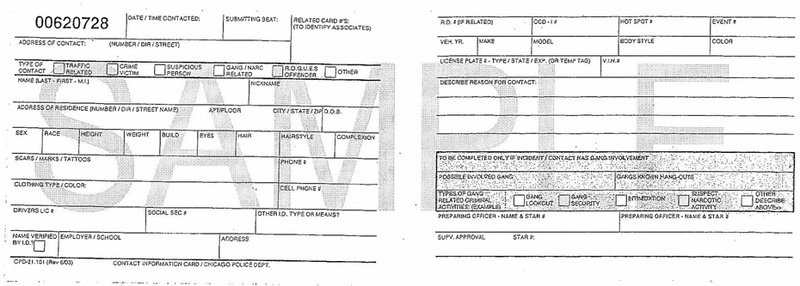

While dismissed, a 2003 lawsuit filed by Olympic gold medalist Shani Davis, Davis v. City of Chicago, first informed the ACLU of Illinois (ACLU-IL) of the Chicago Police Department’s stop and frisk data collection method using contact information cards. This prompted the ACLU-IL to file two FOIA requests, including one from 2010 data that found 10 percent of stops to be unjustified. However, this analysis of data was shaky as the sample size was small; Chicago PD released only 298 narratives out of the 177,000 on record for the six-month period.

Despite attention drawn to Chicago’s stop and frisk practices, there has been no successful analysis of the state of stop and frisk practices within Chicago PD. This lack of analysis can be attributed to the poor data collection methods of stop and frisk data that fail to discern what type of police encounter the card is reporting: Terry stop, citizen encounter or gang/narcotics-related loitering enforcement. Further, unlike New York and Philadelphia, Chicago did not undergo successful litigation resulting in court mandates for stop and frisk data collection. Because of the poor data collection practices in Chicago, stop and frisk data simply doesn’t exist.

Data collection, quality and accessibility

While the Chicago Police Department does collect data on stop and frisk occurrences, it uses standard field contact cards that fail to produce usable data. The contact cards have not historically differentiated between citizen encounters, stops, frisks and searches. But, in result of the 2012 lawsuit Hall et al. v. City of Chicago and an updated Chicago PD special order, citizen encounters are no longer documented on contact cards. Today, Chicago PD officers are directed to document only “investigatory stops” (i.e. Terry stops) and instances of “enforcement of the Gang and Narcotics-Related Loitering Ordinances” on the contact cards. Even with a reduction in uses for a contact card, contact cards do not communicate what kind of police encounter occurred.

To make matters worse, crucial information contained on the contact cards is written in narrative form by officers and is not quantifiable, leaving them nearly impossible to analyze on a large scale. Officers are required to include many important pieces of information about a stop in the written narrative field including: reasons for a stop, description of the suspected crime, information on if the person was frisked or searched and if a weapon or contraband was found. This information is integral in determining if a stop and frisk was conducted — and if it was lawful. Because the written field is almost impossible to analyze, data on the number of and reasons for stop and frisks is nearly nonexistent in Chicago. Despite observed increases in contact card use, there is no database to access data on Terry stops in Chicago. For instance, in the first 10 months of 2013, Chicago PD completed over 600,000 contact cards, compared to the 516,500 from 2012 and the 379,000 in 2011. There is an increase in Chicago PD’s use of contact cards, but it is unknown if the cards are being used for more Terry stops or “enforcement of the Gang and Narcotics-Related Loitering Ordinances.”

The ACLU-IL has requested the City of Chicago to implement a publicly available stop and frisk database (Chicago PD currently has an electronic database for contact card data) which would create more accountability for the city’s police force.

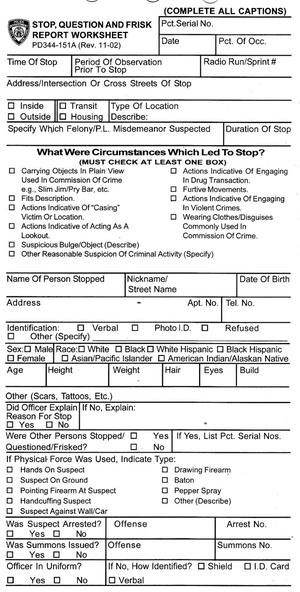

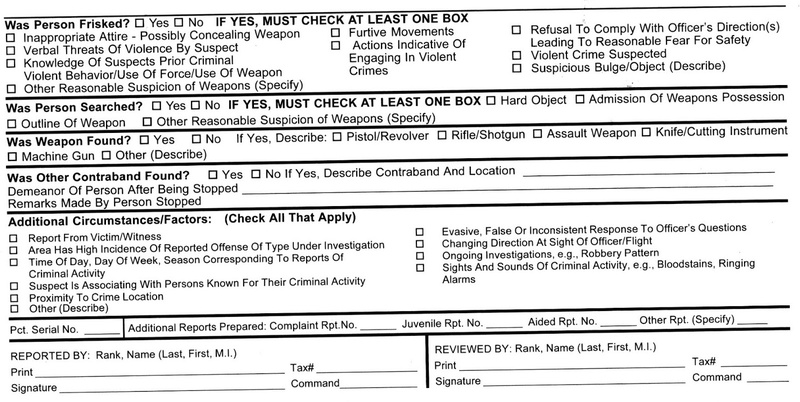

Conversely to Chicago, the NYPD has been successful in collecting and analyzing stop data due to its use of a form dedicated to recording all levels of citizen encounters. The form, a Unified Form 250 (aka UF-250), requires the officer to collect information on many aspects of a stop including demographic information on the individual, reasons for stop and an explanation of the event. Unlike Chicago’s contact cards, data collected on the UF-250 is measurable.

Despite the NYPD’s success in collecting and making available raw stop and frisk data, data has historically been released in an inaccessible format, .por. This file type is an SPSS Portable File and is opened using SPSS, an expensive software often used by academics for statistical analysis. Because this data is released as a .por file, it makes it difficult for the average citizen to open and use the data. In 2008, the NYPD made its 2006 stop and frisk data available in multiple formats (including the more accessible delimited text format) showing that it is possible for the NYPD to make this data available in an open format. On Monday, with the NYPD’s release of 2014 data, the Department made improvements by making all stop and frisk data available in both .por and .csv formats.

Philadelphia’s Bailey ruling mandated the collection and analysis of stop and frisk data. However, Philadelphia has yet to make its stop and frisk data to the publicly available despite it being regularly released to ACLU-PA for court mandated review. These court mandated reviews do not publish raw data but rather results from analysis on the presence of racial bias in Terry stops. The findings are released in .pdf format on an annual basis.

Similar to Philadelphia’s annual .pdf reports, the LAPD also published biannual reports from 2001 to 2007 in .pdf format. But, unlike Philadelphia, the LAPD’s reports included aggregate numbers on stops by race, gender, and age as well as counts of reasons for a stop, what was searched and if an arrest occurred. Despite the reports being in .pdf format, the reports produced by the LAPD communicated more detail about the state of stop and frisk than the Philadelphia reports. The dissolution of the consent decree in 2009 ended the publication of stop and frisk data reports — as well as the simple collection of this data. Due to this lack of data collection, the state of stop and frisk in Los Angeles today is greatly unknown.

What can we learn from these cities?

In New York, Philadelphia and Los Angeles, court-mandated data collection and review helped hold police departments accountable for officer actions and ultimately reduced unlawful stop and frisk practices. But, as seen in Los Angeles, with the absence of an external body mandating the collection of this data, the priority for data collection can fall by the wayside. It is necessary that the data is collected and disseminated, but it’s also important that the cultural change have support from within the police department. Without this support, the data may disappear alongside expiration of court mandates.

The digitization of stop and frisk data was integral to the accountability made possible by court mandates in Los Angeles, Philadelphia, and New York. However, the creation of an electronic database was not as successful in Chicago, where the method by which the data is entered into the database was unusable. Chicago acts as an example that it is not just necessary to collect data, but also to collect usable data with measurement and analysis in mind.

Aside from the importance of the collection of police data, it is also important that the data be disseminated in a form usable to the public. As exemplified by New York City’s past publication of difficult-to-open .por files, making data available is worthless if it cannot be easily accessed. In Philadelphia, data is released only to the ACLU-PA, whereas public .pdf reports are full of results and analysis — not usable data.

Curious if your police department makes stop and frisk data publicly available, or collects it at all? Contact your department or check out their website and let us know what you find.