OGP: Opportunities and Limitations

It’s been two years since the Open Government Partnership (OGP) was first announced. As Sunlight shares recommendations for the US’s OGP National Action Plan, we’re looking forward to attending and participating in the upcoming summit in London.

It’s been two years since the Open Government Partnership (OGP) was first announced. As Sunlight shares recommendations for the US’s OGP National Action Plan, we’re looking forward to attending and participating in the upcoming summit in London.

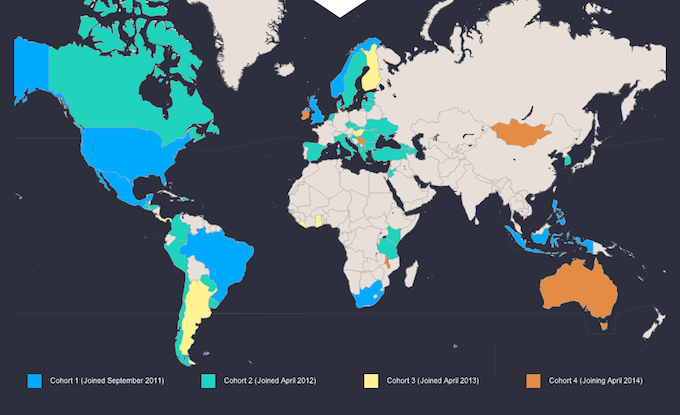

OGP has demonstrated explosive growth, with the initial 8 founding countries expanding to 60 in a very short time, and more likely to be announced soon. This rapid expansion is an affirmation of government officials’ desire to grapple with transparency issues, and demonstrates an appetite — particularly from the public — for “open government” and making it more accessible to the people it serves. OGP has been important in helping governments move in that direction, particularly Brazil’s passing a new FOI law and the US committing to implement the EITI.

OGP itself has been quite open in discussing its limitations, and no doubt there will be more of that at the next meeting. But it’s important, in advance of the upcoming summit, to offer a few observations about OGP’s structural limitations to provide context for the new national action plans.

Many of the concerns and observations here are grounded in Sunlight’s experience with the Obama administration since 2009. It has taught us that it is important to find the right posture in our response to the Open Government Partnership — to take advantage of the opportunities we’re presented with, while at the same time holding government’s feet to the fire.

First, in designing an international initiative that governments would be willing to sign onto, OGP has permitted governments to define for themselves what openness means. The eligibility criteria do set some minimum standards for entry, but those minimal standards (like having an FOI law) only define which countries can join the initiative, and don’t guide countries’ participation, or the way they are evaluated. The drive to build national action plans through a “consultative” process is an effort to overcome this limitation (that governments pick their own commitments), but consultation is often just a few pre-planned, post-hoc conversations with civil society groups.

OGP is built around countries’ national action plans which are voluntary, self-imposed, often enormously vague (for example, the US committed to using technology to strengthen the Freedom of Information Act, an unmeasurably vague commitment), and only delivered every two years. The Independent Reporting Mechanism (IRM) — OGP’s system for measuring progress on action plan commitments — accepts governments’ commitments at face value, essentially providing no evaluation at all beyond the terms that governments set for themselves.

The OGP national action plan process does have all sorts of benefits, such as creating conversations and international connections where they didn’t exist before. Sunlight has certainly benefitted from our frequent meetings with White House officials throughout the OGP process, and we assume governments and outside groups around the world have shared that experience.

The National Action Plans to date have committed themselves chiefly to low-hanging fruit (like the frequent, “open data” commitment), resulting in a bias against fundamental questions of power, like military and state power, or money in politics. OGP’s incentive structure to join the overall effort prioritizes the easy questions over the hard ones.

But political reality has shown us that the openness we are demanding from modern democracies has rarely developed through the good will of officials who hold power. Access to information laws, national regulatory systems, and accountable public processes — the landscape of government transparency that defines our public sphere — have often come only after intense struggle, revolution, scandal, elections, and public organizing. Voluntary commitments — particularly given their vagueness — can play a productive role, but they’re no replacement for the rule of law. And OGP commitments do not have the force of law, or even a commitment that extends beyond the term of the current head of state.

The OGP requires extensive consultation with civil society in the development of their plans. But this emphasis on consultation, with no guarantee of civil society priorities being represented in country plans, leaves civil society organizations (CSOs) in a difficult situation. CSOs need to distinguish between productive meetings that may lead to useful outcomes, and meetings designed to legitimize whatever governments have already decided to do.

I suspect that in the end some of these questions may be unanswerable ones, because the action plans’ primary purpose is to serve as an organizing instrument among countries. Sometimes National Action Plans will cause important new reforms (like the EITI commitment from the US), and sometimes they will not, but in a sense the action plans’ primary purpose is to build a movement, and to strengthen cultural expectations for government transparency. If that endeavor is successful, it would be a small price to pay if we give up verifiable rigor in the evaluations of countries’ action plans. But we should also be clear about the depth of our expectations.

~

Just as Sunlight has done domestically, internationally we’re working hard with allies and peers to raise new expectations for how government transparency should function, even in the face of often disappointing plans. We’ve encouraged the proliferation of open data initiatives in the US, and done what we can to strengthen our expectations for how they function internationally. That’s the motivation behind the Open Data Policy Guidelines, the Procurement Open Data Guidelines, the Global Open Data Initiative, and OpeningParliament, to name a few.

We’ve also gained a new appreciation for the importance of moving beyond voluntary commitments, working to enact laws to ensure permanence and oversight. And we’ve deepened our commitment to dealing with fundamental issues of fairness and power, like money in politics, since they’re the issues that are the least likely to benefit from internal pressure, and are in need of civil society attention.

Many of these same approaches are valid for OGP. We all must push governments to go beyond voluntary commitments to enact legal requirements and standards for governmental openness. We must help governments set priorities based on citizen’s needs. We must push officials to recognize their responsibility to address fundamental issues of power, like surveillance, national security, and the influence of money in politics. And we have to balance our own priorities, seeking consensus when appropriate, without giving up on our ability to judge the world against our ideals.

As we all figure out the right role OGP can play in our work, we should be mindful of the opportunities and limitations it presents, so that we can use it for all it’s worth.

Photo via the Open Government Partnership