Why is our tax code so lame? Or, what we can learn from Caterpillar and Dave Camp

Today being tax day, it’s a good time to take a few moments to reflect on some of the pathologies of the U.S. tax code and why they are not likely to change anytime soon.

Exhibit A is the case of Caterpillar, the latest multinational company to come under the scrutiny of Sen. Carl Levin, D-Mich., and his Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations. Recently, Levin’s committee released a blockbuster of a report on how Caterpillar had used Swiss subsidiaries to save $2.4 billion in taxes. That’s a lot of money, that $2.4 billion. For those keeping score, it’s roughly 63 times the $37.9 million that Caterpillar has spent to lobby the federal government since 1998.

Caterpillar is part of a bigger story: the relationship between how much companies lobby and how little they pay in taxes. For example, of the eight companies that spent the most on federal lobbying between 2007 and 2009, seven decreased their overall tax rate between 2007 and 2010. And six of the “Big Eight” enjoyed a decrease of at least seven percentage points.

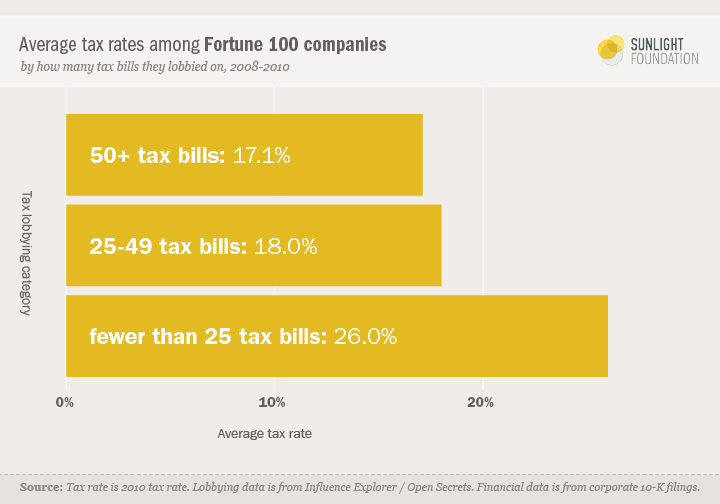

Or, consider the Fortune 100 companies that lobbied on the most tax bills between 2008 and 2010. The 10 companies that lobbied on 50 or more bills since 2008 paid an average effective tax rate of 17.1 percent in 2010. The 10 companies that lobbied on between 25 and 49 bills (one of which was Caterpillar) paid an average effective tax rate of 18.0 percent. The remaining publicly-traded Fortune 100 companies paid an average effective tax rate of 26.0 percent. The companies that lobbied on the most tax bills also have seen their tax rates decline the most since 2007 (see Figure 1 below).

The most comprehensive academic analysis of this question, published in the American Journal of Political Science, finds that “Firms that spend more on lobbying in a given year pay lower effective tax rates in the next year. Increasing registered lobbying expenditures by 1 percent appears to lower effective tax rates by somewhere in the range of 0.5 to 1.6 percentage points for the average firm that lobbies.”

Some of the lobbying involves protecting the existing loopholes, like the ones that benefit Caterpillar. The rest involves pushing for small changes to the tax code to narrowly benefit companies or industries. According to a 2005 report from the President’s Advisory Panel on Federal Tax Reform: “Since the 1986 tax reform bill passed, there have been nearly 15,000 changes to the tax code – equal to more than two changes a day. Each one of these changes had a sponsor, and each had a rationale to defend it. Each one was passed by Congress and signed into law.” In 2011, the IRS’ own ombudsman estimated the length of the U.S. tax code to be 3.8 million words – or about 6 ½ times the length of the famous Russian novel War and Peace, for those reading at home.

Not all of Caterpillar’s lobbying budget goes to tax lobbying, of course. But of 165 lobbying reports that Caterpillar filed since 1998, 130 (79%) mention tax issues, making it the company’s top issue.

Looking more closely at these 130 lobbying reports, 46 mention either the phrase “international tax” or “international corporate tax.” Another 22 mention “subpart F,” the section of the tax code that deals with controlled foreign corporations, which is what Caterpillar employed in avoiding those taxes.

Why reform never happens

Earlier this year, House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Dave Camp, R-Mich., put forward a 979-page plan for tax reform. It was an ambitious plan, but it made the fatal mistake of every other tax plan before: It challenged the interests of an industry with a lobbying presence in Washington (well, actually, several industries). Therefore, it was dead on arrival.

As Alexander Furnas and I documented last year, pretty much every industry lobbies on taxes, and, as we wrote at the time, “Lobbyists representing pretty much the entire economy are well entrenched and prepared to defend a dense thicket of interlocking interests to protect favored loopholes, credits and other tax favors. Their attention is both wide and deep.”

Every year, it seems, there is yet another call for tax simplification, another bold plan or proposal to attempt to solve what experts can agree is “a hopelessly complex mess, antithetical to growth, and… crammed with conflicting incentives.” Every year, that proposal dies in committee, before anybody has to make the hard choices that would upset some industry or set of companies with lobbyists ready to pounce at the slightest suggestion that they would be targeted “unfairly.”

Caterpillar is just the latest of many companies to be called out by Levin’s subcommittee. Last year it was Apple. Before that it was Microsoft and Hewlett-Packard. Not much has happened to change how these companies operate and pay taxes. A good guess is that nothing will happen with Caterpillar either. After all, they’ve been lobbying to keep their loopholes in good shape for a long time, and they are probably pretty good at it by now.

—– So on this tax day I will leave you with three guesses.

My first guess is that Caterpillar will continue to lobby to prevent any changes to the loopholes it enjoys, and soon this latest report will be forgotten, just like the ones before it. After all, Levin — one of the few consistent crusaders against corporate tax avoidance — is retiring this year.

My second guess is that more companies will hire more accountants and lawyers and lobbyists to come up with more tax strategies, because when you have a tax code as big as we do, there are probably infinite ways to exploit it.

And my third guess is that senators and members of the House will continue to propose and then drop comprehensive tax reform. After all, if there weren’t the constant looming threat of tax reform, all those tax lobbyists would have a lot less to do.

I’d even be willing to put money on all that. As long as my earnings would be tax-deductible. I’ll ask my accountant to come up with a way. There’s gotta be something in that tax code to help me out…