Complete financial opacity in record-breaking Indian elections

More than 814 million voters are going to the polls over India’s six-week (!) long national election, 300 million more than the next three most populous democratic nations (the United States, Indonesia and Brazil) combined. In an election campaign estimated to cost almost $5 billion USD — a sum second only to the 2012 US presidential polls — the world’s largest democracy faces serious issues, as its opaque political finance regime leaves those 800 million voters in the dark about who is funding the campaigns.

Corruption is business as usual

Living in a country where corruption is seen as “the business of politics,” Indians have little to no chance to follow how the rich and big businesses influence the results of their elections through financial support to the campaign.

The country has hardly any legal requirements for political parties and candidates to disclose individual donations, and corporate donations — whether to political parties or individual candidates — are also seriously underreported. (Though some level of reporting is required for business entities, that does little to fill in the overall picture.)

Election guidelines in India allow candidates to spend up to about $110,000 on campaigns, but transparency advocates warn that the real cost of winning a parliamentary seat is about 10 times as much as rules allow. Based on a cost analysis from previous local and state elections, the New Delhi-based Centre for Media Studies has estimated that politicians will spend a total of 300 billion rupees (around $4.95 billion USD) on this year’s elections — including cash stuffed in envelopes and multi-million-dollar ad campaigns.

According to most recent studies, this sum might help to boost the country’s struggling economy in the short term, and benefit a range of businesses such as media groups and advertisers, but the long-term effects are devastating. In a country with hundreds of millions of illiterate voters, extreme poverty, and politicians that are either billionaires or have criminal histories, big money involved in polls is increasing inequality tremendously, and inequality is already a burning issue for Indian society.

Any chance for reform?

Through a pessimistic lens, there is no strong indication that any of the electoral outcomes will strongly affect the transparency of money in politics in India.

True, the current administration seems to have recognized the potential of technology and openness when launching an open data portal or organizing the country’s first hackathon. But the very same government also tried to amend the country’s freedom of information legislation in a way that keeps political parties away from public scrutiny while taking bribes estimated to be between $4 billion and $12 billion. And the political alliance likely to get elected is led by the nationalist opposition Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), one of the six parties that refused to disclose the financial contributions they have received.

From a more optimistic perspective, Indian democracy has never been so ripe for reform.

As we wrote about a few months ago, the country’s 2005 freedom of information law has already made a tremendous impact on how Indian politicians respond to public scrutiny efforts. Last year, we saw a heated public debate around the finances of political entities with the Central Information Commission ruling in its landmark judgment that parties should come within the ambit of the sunshine law.

Indian parties have of course done their best to exclude themselves from the law ever since. But the country’s broken and opaque political finance regime is now heavily disputed by its civil society, with citizen campaigns like the RTI Call-a-Thon or the Coalition Against Corruption Conference, an attempt of Janaagraha (the organization behind the world-famous iPaidaBribe website), Sunlight and Stanford’s Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law to bring the influence of money in politics to the spotlight.

The role of civic technology

Besides the increased awareness around the issue, another encouraging sign is the role civic technology plays on the subcontinent. As we have seen in so many other country cases, civic technology projects — even if they don’t immediately bring about change — have an enormous potential to increase democratic consciousness and change the expectations about how politics should work, especially in a country with a rapidly growing population of young people.

The country’s heavy investment in the IT sector and its sheer size make India a sweet spot for tech giants, now competing for potential users through their democracy projects.

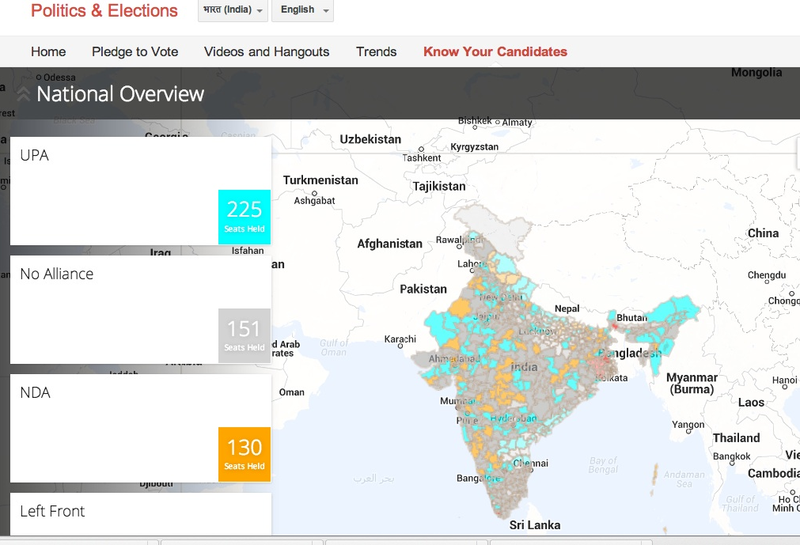

Facebook, for instance, teamed up with Times India to engage young people in the voting process through an election tracker. As TechPresident points out, such social pressure can boost voter turnout tremendously, especially when the endorsement of voting comes from friends. Google, meanwhile, created a portal that pulls in and visualizes all kinds of election-related data such as information about political parties and candidates (including their criminal cases and assets).

We are curious to see how the youth of India, alongside the country’s vibrant civil society might create a change by demanding more transparency from their elected officials. The wish list of all the issues that the new Indian government should tackle is probably as long as the country’s voter list, and dealing with rampant corruption is one of those. Increasing the transparency of political financing would be crucial to understand the influence agenda and to fight grand-scale corruption in India.