How to invite feedback on an open data policy

Sunlight Foundation: So, Matt, set the scene for us. Give us some background on your role with OCTO and your focus on open data.

Matt Bailey: When I came into the role of Director of Tech Innovation in 2015, we immediately recognized the need to do something related to open data. One of the first tasks that landed on my desk was to draft an open data policy. Fortunately, there was top-down support for open data and some history, with D.C. being the first US city to share its data catalog online as open data. At the time, the Mayor wanted to do something big and harmonize it with some of President Obama’s open data initiatives. So rather than advocating up for why we should take on this project, I was empowered to write something and go big on it, which was really exciting.

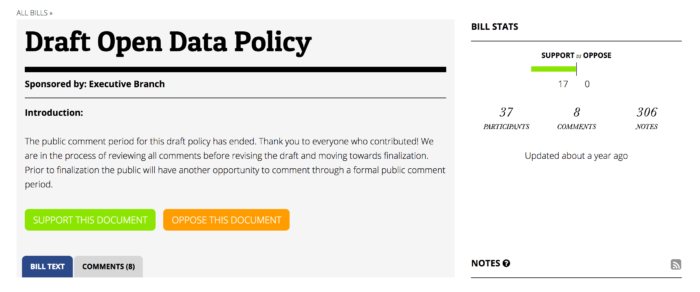

SF: And part of what you did to go big was to develop this draft policy collaboratively, in the open, on the Madison online platform. Was Madison a tool that the city had already been using or was this something your team dove headfirst into as part of the open data policy?

MB: Part of the reason we decided to go really big on soliciting public feedback is because it was something the city had been doing a poor job of in the past. There was a Mayoral Order issued under the previous administration that contained a public feedback period and was posted on the city’s website, but it hadn’t really engendered much of a dialogue. There was some great stuff in there, but also a lot that could have benefited from public feedback. Ultimately, the draft open data policy was a great opportunity to teach the city another way to think about community engagement and about the policy drafting process with a new online platform.

Given that we didn’t have much of a budget, and had very few people to do outreach, we wanted to use a platform that was as inclusive and as intuitive as possible. We wanted to ensure it was very easy for the public to provide feedback. At first we considered putting it up on Github and using Github comments, but eventually we landed on the Madison platform which is a product of the OpenGov Foundation. Drafts.dc.gov (an instance of Madison) was created as a part of this effort.

Madison was better for us because it meant people who care about government data but may not be technologists (think reporters, or people who file a lot of FOIA requests) don’t have to create a Github account or figure out what a pull request is in order to weigh in. Madison was also already in use in DC. Councilmember Grosso’s office had piloted and it was gracious to allow us to port their copy of Madison to the Drafts.dc.gov domain so we could build off their efforts.

SF: As you’ve said, DC had some existing open data practices and a mayoral order on the books. So was this new effort about re-legitimizing these existing practices with a new administration? Was it about revisiting it and improving the policy? Or both?

MB: Both. It was at the time a very young administration, wanting to do big things. We were encouraged to look at it and potentially pull provisions forward, but really think about it in terms of “what would be the best version of this policy?”

The basic idea for doing it via drafts.dc.gov was this this: It would be the completely wrong approach if I, a person who knows some stuff about open data, wrote a policy and then shared it with people in the administration who know probably more about policy but less about open data, and then we all agree what a good policy looks like. That’s not a way to reach an ideal policy, especially when there are people who have been working on open data for nearly twenty years outside of city hall.

We also wanted to take advantage of outside expertise, beyond what was inside city government. We already had a civic hacking community who had advocated for the policy. We considered hosting virtual townhalls so that people across the country, or those who had time constraints, such as childcare, could have the opportunity to weigh in.

SF: Were you concerned at all about not getting any feedback once you put the draft up?

MB: Frankly, we weren’t too worried, given the policy’s nature. And as it turned out, just a little Twitter push was helpful to get a lot of people to jump on and start weighing in immediately.

SF: How else did you invite participation? And how did you know who to invite?

MB: One thing to ask yourself is, who do you need to get feedback from in order to ensure you’re representing all voices, and where is that need most extreme? For example, if you’re putting up a tech-driven platform and you’re writing policy that is affecting affordable housing, you risk magnifying the voice of the people who are already most likely to be in the conversation and minimizing the voices of the people whose perspectives are needed most.

In this case, I was lucky because me and some of my colleagues already knew the landscape of interested groups so we didn’t have to do a lot of research. We were also lucky to be already connected to them via Twitter, and through various Slack [channels] and community events.

Most of our outreach was online. We did attend a couple of events, such as Code for DC, where we spoke about the draft and made sure people were aware, but ultimately we found that digital outreach was most effective. For example, we posted on the Code for DC Slack, where we reached a lot of people who are very interested in open data but don’t necessarily come to all of the meetings.

It was important that we weren’t just reaching out once to check a box, but were actually regularly reaching out, almost treating it like a campaign. We tweeted regularly from our personal accounts, as well as the OCTO and Mayor’s accounts. We’d tweet when we reached particular milestones, even just in terms of the number of comments received. We’d tweet at groups that might be relevant, making sure to cast a wide net. So in DC, we’d reach out to local groups, like the Open Government Coalition and a variety of local hacking groups, but also those people or groups who care about technology more generally. These folks have a lot more followers than us, and also had the ability to reach into some of the community networks we may have missed.

It was also really important to make sure that people felt it was real. We didn’t just put up a website and say, “Okay we’ll be back at the end of this process to see your feedback.” We were on Madison reading the comments at least once a day, going through each comment, moderating the conversation in a light way. There were quite a few cases where there was a spirited debate back and forth and at least one person in the conversation kind of got a fact wrong or needed a bit of additional context, for example, to understand the definition of a particular word.

SF: Do you think when commenters saw your response it made it more real and showed that the District was actually listening to contributions?

MB: Unrestricted to the open data or open government community, people fault the government for not doing a very good job at active listening. And so people rightly come to a public comment period and kind of think nobody’s going to read what they have to say. What we tried to do, relatively successfully, is to be very non-editorial, non-defensive, very factual and very grateful for the engagement. We would literally say “thank you” to people who provided feedback.

SF: What was your experience dealing with comments that you felt were unproductive, misinformed, or critical?

MB: There’s always the risk that somebody’s going to be unproductive or anti-administration, but the harm compared to the benefit of crowdsourcing wisdom about how to make the policy as good as possible — in this case, people commenting globally on a city-level open data policy — that’s so much more important than if somebody’s on there typing in all caps.

In this case we really didn’t see much of that at all. There were a handful of comments that had a negative tone, but that’s understandable. And criticism gave us an opportunity to say, “we may have gotten it wrong, and here’s how we got to this point.” These conversations added value to the end result. And it wasn’t like we were in there all of the time commenting; it was a lot more useful to have residents creating a discourse among each other.

SF: Did you have to get any sort of permissions from the DC communications office or anyone in PR in order to have this direct communication with public commenters, or were you given more free reign?

MB: One of the things we did to mitigate communications concerns was to hold a meeting within the team to discuss our editorial strategy: what our voice would be and how we’d respond to comments. This helped with consistency. We then shared our editorial guidelines with our comms people to help them understand that there wasn’t much risk. We weren’t speaking as the mayor, we were limiting our interactions as much as possible, and we were being purely factual.

SF: What methods did you use for deciding which feedback you’d incorporate? How did you respond to situations where you received conflicting feedback from your audience?

Situations where we received conflicting feedback were the most useful. The single best thing about this public feedback process is, as compared with a standard “send us an essay and we’ll consider it all” process, is that people were disagreeing with each other. “What’s the right definition of data?” is the perfect example. There’s no right answer and there’s a lot of really interesting perspectives. In some cases it wasn’t a matter of accepting or rejecting a comment, it was about refining an approach based off of the collective input. So what we did to adjudicate comments is export comments to make a big spreadsheet and literally went through every single comment, both in a stand-alone fashion and then in the dialogue in which it was written. Then we assigned them dispositions: is this something we want to immediately accept, and we should make the change now? Is it something we need to address, but can’t incorporate directly in its own fashion? Should we run this issue up the flagpole? We made up that list of dispositions in 5 minutes. It wasn’t rocket science. It took hours to go through, but it was worth every minute.

SF: How important was having public-facing documentation to explain how you were, or were not, incorporating specific comments?

MB: We had originally planned to put that spreadsheet online, but didn’t get around to it. What I’d really like to see is a documented process for adjudicating comments that includes transparency into what was accepted, what wasn’t, and why. Even if no one reads that spreadsheet, putting it online is symbolically important. For a city, it would illustrate the comments are taken seriously, which could help drive engagement in future policymaking.

SF: How did you decide when you’d received enough feedback and could stop soliciting comments?

MB: We wanted to to make the comment period generous, but not open ended. I think we left it open for 4 weeks and in our outreach we communicated that specific window.

SF: How was the process received by the Mayor’s office or others “up the flagpole”?

MB: They were very excited about it, and I think If anything, they wanted it to be bigger. There was a member if the administration who was very supportive but at one point said, “this is great, but you’re talking about 300 comments for a city 650 thousand people”. It’s very impressive and it’s way more comments than we usually get, and it’s way more robust, but we’re still talking about a tiny drop in the bucket. So I think that’s the question, and I don’t think it’s one that can be answered for this type of engagement, which is “how do you scale it?” The platform will support it, but how do you actually get a meaningful cross-section, and how do you know that you actually got a meaningful cross-section that’s not demographically skewed?

SF: It sounds like you and your team were very connected to relevant community stakeholders with an interest in open data. Any advice for city staff who might not have those connections?

MB: Talk to your peers and learn from them. Pull up examples from other cities who have done this and see who you’re missing. Find out who’s commented previously and reach out to them. In particular, find the people who have been examining these issues coming from civil society or academia. They’re going to be excited to hear from you.They took time to comment on something as esoteric as your open data policy. Why wouldn’t you email them and solicit their feedback directly?

The other aspect of this is the in-facing relationship building, not only within the Mayor’s office but also the data stewards within DC government. I had a lot of meetings with directors of agencies, people who were running programs, or people who were collecting data, to talk through what we were thinking about putting out and spots where there might be problems. We were asking questions like: Who runs your permitting systems, how many are there? Are there more than one person running it? Do they actually work together? Who else works with data like that? Do they talk to each other? It was an immense opportunity to connect the dots on the graph inside of government.

SF: So in a way, did the public dialogue explicitly help you have the internal conversations?

MB: Yes. If everybody just agrees with the draft policy, then we’ll have to issue it.Some of the most interesting conversations i had were with people who were running programs to help out survivors of domestic abuse. They were holding a bunch of really sensitive data. They told us that about data collected by a different agency that wasn’t directly related to their operation, but may not be appropriate to release alongside their data because it could increase risks to victims. It was useful not only from the standpoint of getting the tentacles of open government expanded across city agencies, but also for making the conversation about data, open data, and data stewardship much more robust within DC government because a lot of those people were people who had never been invited into the room.

SF: So did you get feedback on the draft policy from government employees on the online platform?

MB: Yes. One thing we did in our conversations — and I think this is something everyone should do — is actively push people to the public channel. To the extent we were receiving emails or people were finding us in the hallways and providing feedback, we directed them to Madison. And it was okay if they did it as an official DC government employee. We wanted that. We wanted all of the perspectives in one place so that everyone could talk to each other.

At the same time, it was also important for us to go and do the sort of “open data roadshow” internally of the policy to provide a non-public deliberative space in order to have these conversations. By the time it gets to the public comment period, you should be debating specifics of words or ideas rather than the overall principles, and you should feel strongly that the draft you put out is feasible.

SF: Cities undertaking a crowdlaw effort often wonder what the right starting point is for public collaboration on a policy draft. What do you consider the right point along the spectrum between blank slate/early ideas to fully fleshed out draft?

MB: My basic view is that you need to fit that to the topic at hand. So if it’s a question that is new and we don’t understand what a good response to it is from a governance or policy perspective, maybe a blank slate or doing some ideation sessions or brainstorming session with members of the community is the right approach, because you may not even know how to articulate the problem. In the case of open data, though, I think we basically understand the problem fairly well. It’s hard. We’ve failed in certain experiments and we may need to try again, but it’s not as if globally with open data we haven’t tried a whole lot of open data policies. So my basic view is in cases where the problem is kind of understood and has been tried before, it’s actually disrespectful to the public to come forward with a blank slate. The flip side of it is the idea of remixing policy. It would have been the wrong approach in this case, for DC in particular with open data, to come put something up blank. In this case, people were so knowledgeable about open data that it was important to bring forward a thing that looks like an actual policy that might be issued. That it had very specific language, it was worthwhile to debate the content. It was very reasonable that the administration might just put it out.

SF: Were there times where you needed to communicate or did communicate from the beginning that there were certain parts you didn’t plan to change, to discourage people from focusing their attention on items where feedback was not valuable?

MB: We didn’t in this case, but I think it’s something we should have been doing — such as directing people to parts of the policy we thought were not as good or were much more open for debate. In order to get it out the door for public comment, it’s already less up for grabs because it’s been through the attorneys and it’s been negotiated up or down.

SF: Did you bring it back to the attorneys afterward?

MB: Absolutely.

SF: One of the things you did was include dates to be filled in. It almost seems like it was an invitation for people to give input on these.

MB: That was actually a really important strategic choice. I would do it again. Those “XX’s” — any time there was a deadline in the policy, we X’d it out because it was not up for grabs. Those were areas where public debate probably wouldn’t have been helpful because it wouldn’t change the logistical reality inside the agencies. So it’s tough because in some cases the public rightly would want to push on as fast a deadline as possible. But we didn’t want to attach a fictitious date and commit one way or the other.

SF: Any final pointers for cities hoping to replicate this process?

MB: It was really important to involve as many practitioners inside the government as possible, including in deciding how to adjudicate comments, encouraging comments online, because a lot of what we’re doing was about culture change. Getting individual civil servants, and at the agency level getting agencies comfortable with and accustomed to co-creation with residents. It’s a really invaluable thing that it happens. Getting members of the actual data teams opportunities to debate or discuss draft public policy — and not just managers, but people who actually work on the day-to-day inside agencies — just openly talking about what the policy should or shouldn’t be. That was one of the most important parts of the approach.