Making the case for human-centered design for open data

Workshop participants use a human-centered design process to plan and launch a citizen science project at an event organized by the White House’s Office of Science and Technology Policy in November 2014. Photo via the Obama White House Archives.

Imagine that a heavy rain caused a pothole outside your house. You make a complaint to 311 but it takes city government weeks to fix it. You’re disappointed by their lack of responsiveness and want to see if pothole complaints in other neighborhoods have taken just as much time to resolve. You go to your city’s open data portal to find wait times for pothole resolution but it’s tough to find the data you need — and once you do, you’re so overwhelmed by the volume of information that you don’t know how to interpret it.

While more than 100 American cities have released data on topics like budgets, crime, transportation, and properties, open data websites aren’t always designed around the needs of residents. When open data is difficult for residents to access, it makes it harder to use. Taking a “human-centered” design approach to open data helps governments engage more closely with their communities and drive social change.

What is human-centered design?

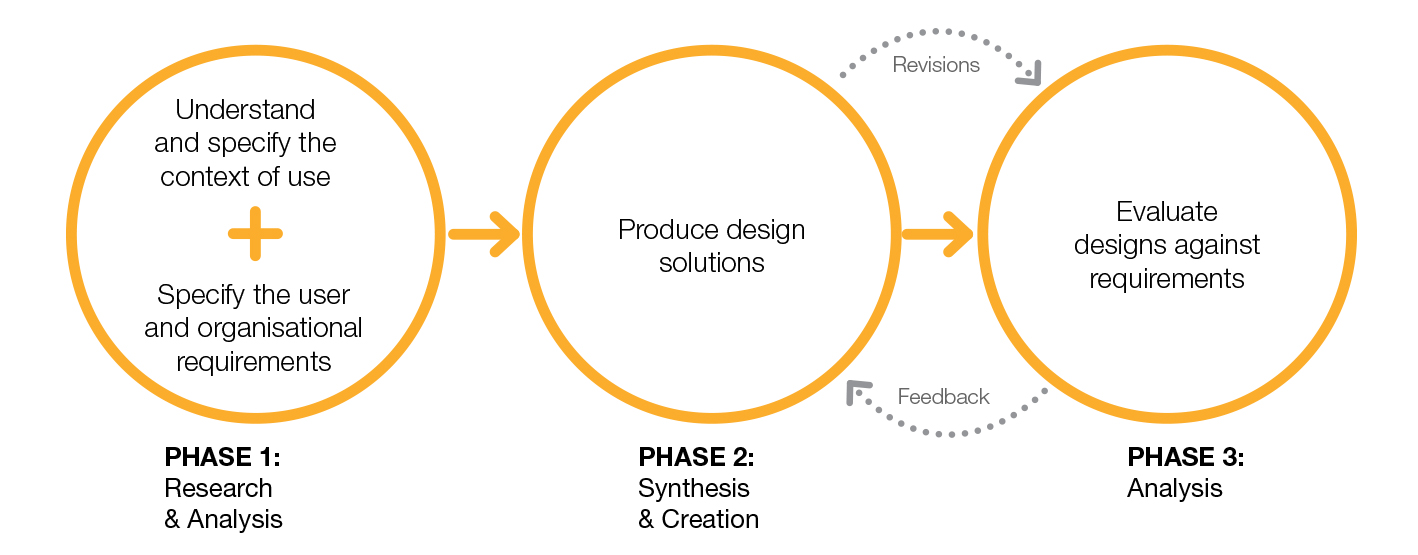

Human-centered Design Model. Image via Visocky O’Grady, 2008.

Human-centered design is a process through which the designer learns about users’ needs, generates ideas with them, prototypes possible solutions, implements an initial design, and gathers feedback to improve it (as demonstrated in the illustration above). Human-centered design is an empathetic approach to solving community problems in which the needs of end users guide the process. By applying this process, city governments can improve user interface (UI) design for open data programs, tailor open data programs to specific communities, and improve residents’ access to open data through data literacy tools.

The focus on end-users is often missing from municipal open data programs, making human-centered design a great opportunity for improving such programs.

Better user interface design inspires public action

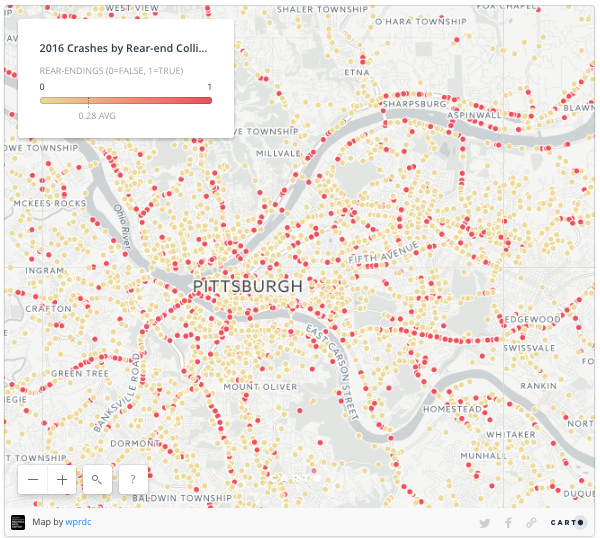

Car crashes in Allegheny County, PA in 2016. Image via WPRDC.

The Western Pennsylvania Regional Data Center (WPRDC) is a great example of an organization that focuses on UI design. WPRDC maintains the open data portal for Allegheny County, the City of Pittsburgh, and surrounding areas. In 2016, the WPRDC collected feedback from the city government, public authorities, and community development organizations at its first Property Data User Group Meeting. In response to the feedback developed at that meeting and elsewhere, the Center developed improvements to their maps, visualizations, and dataset landing pages. These improvements made it easier for residents and city governments to access and use data helpful for use cases such as identifying vacant land or tracking common ownership across multiple properties. Keeping end-users at the heart of an iterative process of “co-creation” has made it easier for people in Pittsburgh to access data and take action.

Human-centered design satisfies needs of specific user groups

A core part of human-centered design is developing open data programs tailored to the needs of specific user groups. By identifying the interests of different users, a city can improve the usability of open data and help its residents make better decisions.

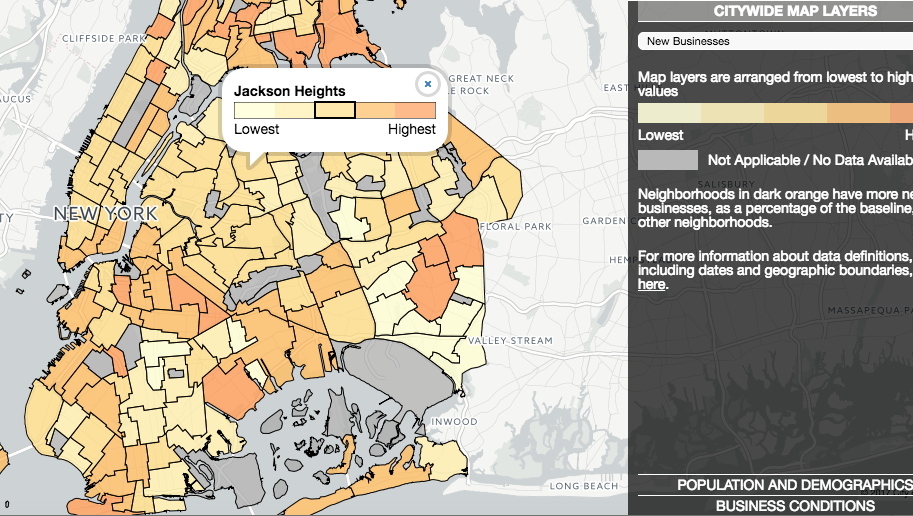

For example, the New York City Mayor’s Office of Data Analytics (MODA) partnered with the city’s Department of Small Business Services to launch its Business Atlas, a mapping tool that allows entrepreneurs to study business and social conditions in different neighborhoods. The data was already available in New York’s open data portal, but its presentation did not offer specificity and context that would be useful to New York’s entrepreneurs. By developing an issue-focused tool in collaboration with small-business owners, MODA helped entrepreneurs get a clear picture of the economic and social health of a neighborhood before setting up their shops there.

NYC Business Atlas shows percentage change in number of new businesses in Jackson Heights, NYC from 2011 to 2013. Image via maps.nyc.gov.

MODA, along with Reboot, a social impact firm, recently launched a report on understanding the users of NYC open data. By interacting with different open data user groups and learning about their needs, they came up with strategies to design open data efforts to better meet the needs of each of these groups.

Data literacy is critical to reap the benefits of human-centered design

It is difficult for residents to give feedback to city governments on open data prototypes if they are not normally able to participate online. That means that improving residents’ data literacy and skills is an essential component of the human-centered design process for open data.

To this end, some city governments, including the Cities of Baltimore and Pittsburgh, host an annual “Data Day.” Their goal is to discuss with public through workshops on why and how open data can can be actionable for communities. The City of New York, in an effort to mark the completion of five years of the city’s Open Data Law, inaugurated “Open Data Week”, which focused on teaching New Yorkers skills that will help them better understand how the city works so that they can provide feedback on it.

Adrienne Schmoeker from MODA conducts a workshop with New Yorkers on what can be achieved with NYC’s open data in March 2017. Image via @GenevieveGaudet on Twitter.

Human-centered design makes it easier for residents to access and use open data, empowering them to become more effective participants in public dialogue and accountability. By designing around the needs of residents, city governments can build trust with specific user-groups and communities, sparking civic action for the greater good. This makes human-centered design a needed approach for open data programs in the cities.