Increase the social impact of open data with user personas

Thinking of a specific person who will use open data (and why) can help cities share that data in ways that are more useful and ultimately increase the social impact of open data. This user-centered focus is a key aspect of our tactical data engagement (TDE) approach to opening data.

Sunlight is currently piloting this approach in Madison, Wisconsin, where we are helping the city improve its open data program. For two weeks earlier this month, we and our colleagues at Reboot conducted user research in Madison to understand who in the community could use open data, how, when, and why.

This is an approach that any city can use. And so, inspired by our work in Madison, Sunlight facilitated a workshop on “Designing for Community Use” last week at the What Works Cities on Tour meeting in Charlotte, North Carolina. Our goal was to bring an abridged version of the TDE user-centered approach to city staff to help them quickly brainstorm who might be potential users of open data, develop “open data user personas,” and then use those personas to design actionable improvements to how their city halls share that data — all in under two hours.

So, how much of the magic of open data user research and design could we capture in under two hours? It turns out, a lot!

Here’s a short recap of what we did, what we learned, and how city staff can facilitate a simple workshop themselves to quickly generate evidence-based recommendations for improving an open data program.

What we did

Our workshop was designed to get city staff in the mindset of empathizing with the people in their community who come to city hall for records, maps, statistics, and all other kinds of public information.

To understand open data users as well as their goals and needs, city staff would ideally spend time talking directly with the people who have a stake in their city’s open data program. This is why we spent a full two weeks in Madison conducting dozens of user interviews in person.

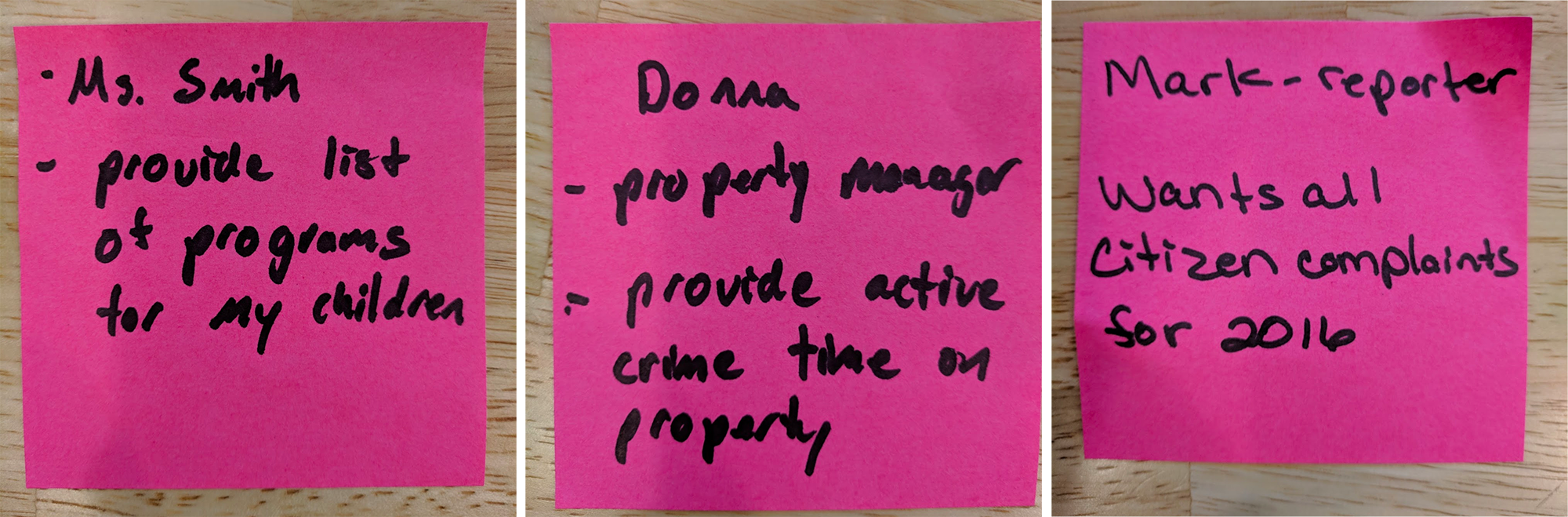

For the purposes of our workshop exercise, though, we didn’t have the luxury of sending city staff out to conduct design research. Instead, we asked participants to think of a recent conversation with a resident in their city — in particular, someone who might have been asking questions or otherwise looking for information — and to ground their thinking in that real human being.

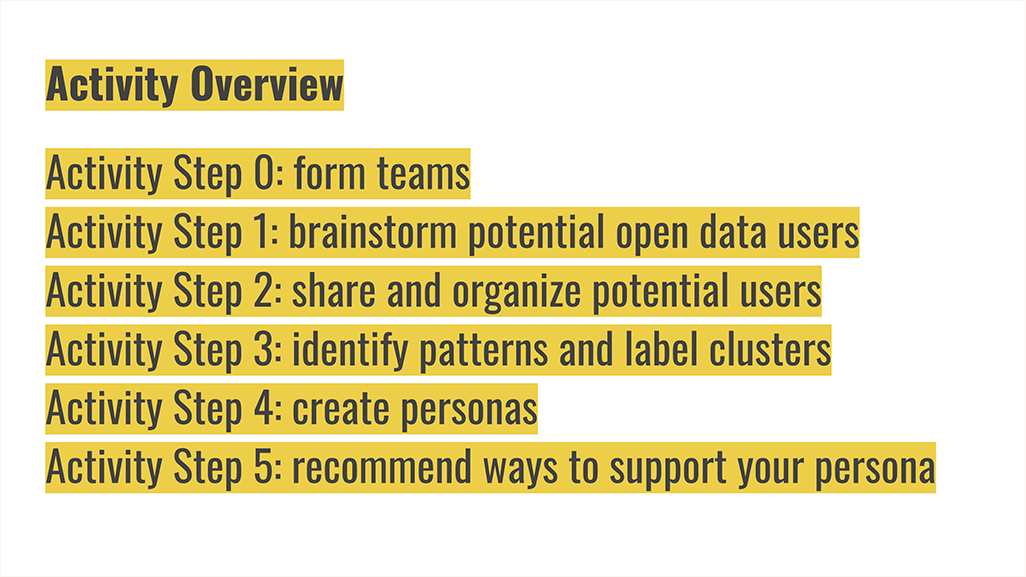

Brainstorm potential users

We broke into teams of 4 or 5 people, and asked everyone to write the names of their users on Post-Its with a few details about what data that person was looking for and why.

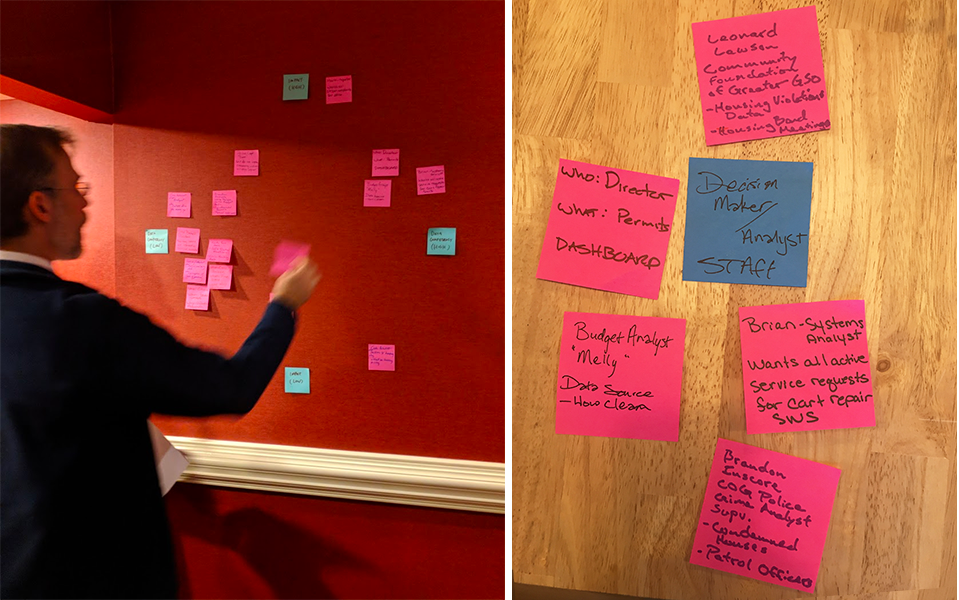

After each team had generated around 15 potential open data users and written their names on Post-It notes, we asked participants to add the notes onto a wall and arrange them into groups. Teams experimented with different organizing approaches, such as mapping users’ data literacy against how much impact that user might have in the community. We encouraged teams to look for patterns and to begin grouping potential users together and assigning descriptive labels to emerging clusters, like “researchers finding trends” or “concerned residents taking local action.”

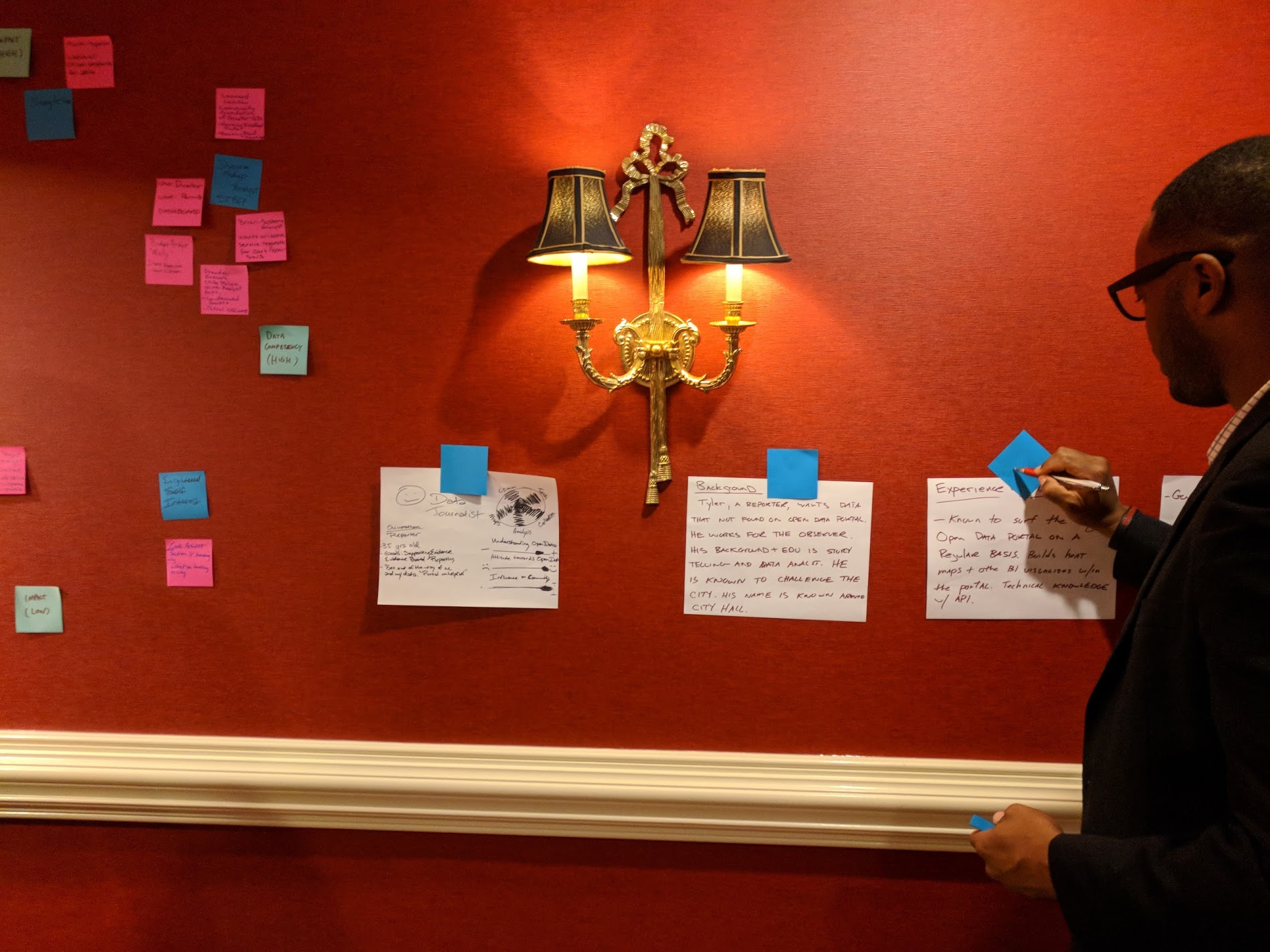

Develop personas and recommend improvements to meet their needs

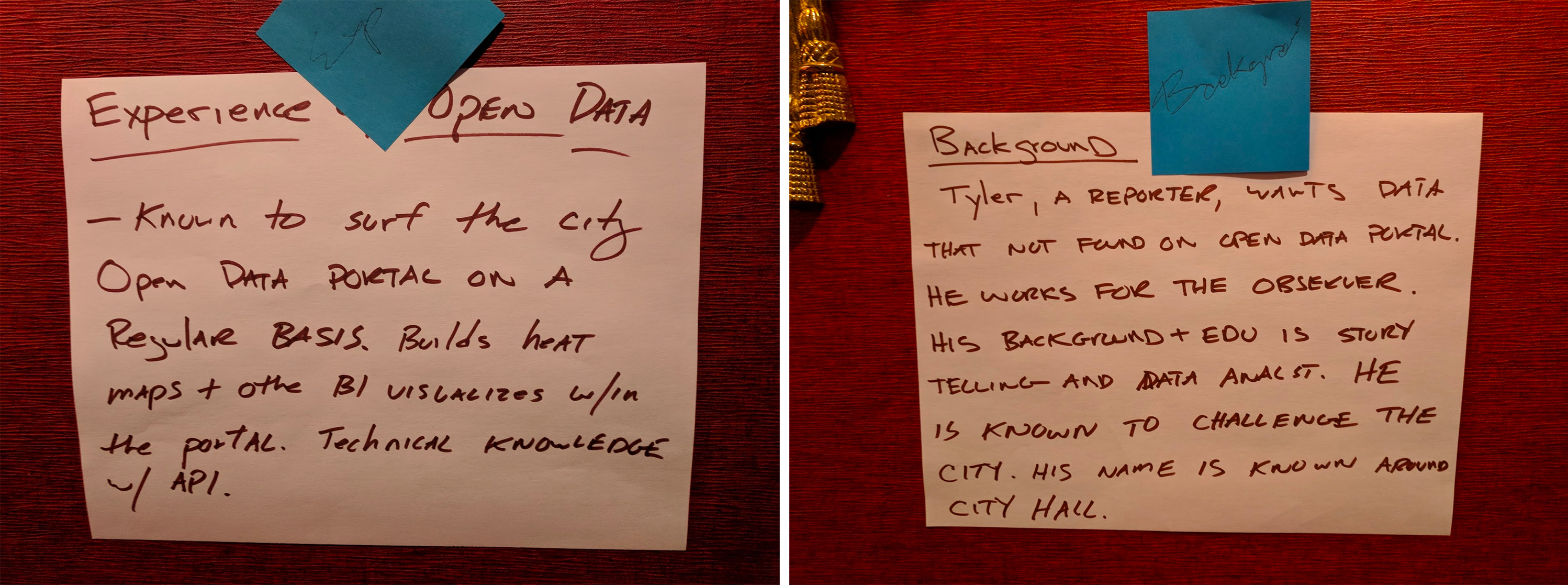

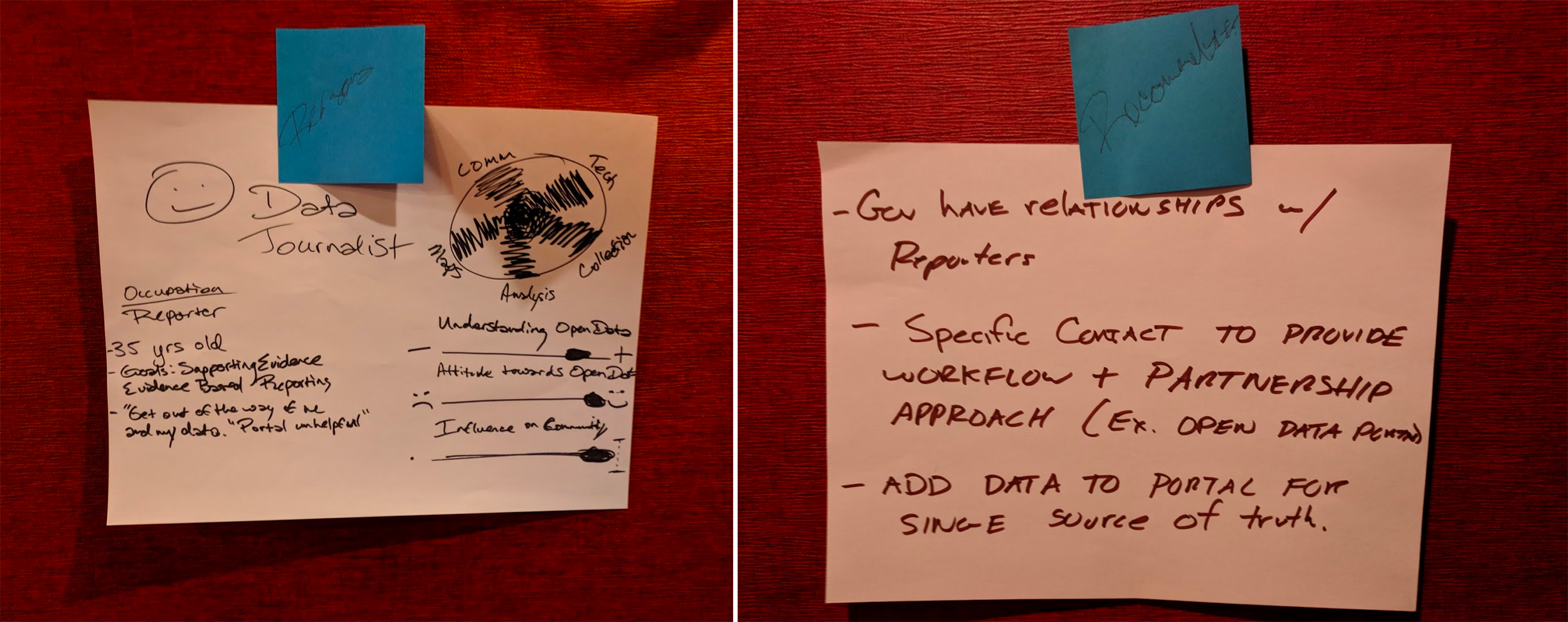

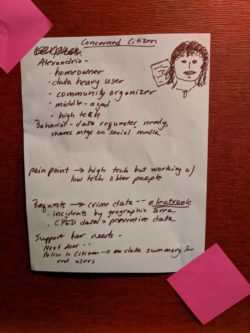

Those groupings are the key to turning a group of specific individuals into an aggregated “persona.” Drawing from the various individuals who made up each cluster, our teams then created provisional user archetypes which unified common themes that those individuals shared. The teams got creative to incorporate details about their user persona’s name, biographical details and background, goals, information needs, pain points, delighters, capabilities, and other behaviors.

Finally, teams put themselves in the shoes of their newly minted open data user persona and used that persona to think creatively about specific actions city hall might take to support that persona’s needs.

The results

By the end of our short workshop, city staff came up with some resonant personas and great ideas about how to support specific community members.

Meet Alexandria. She’s concerned about crime in her community — how could open data help her?

Meet Alexandria. She’s concerned about crime in her community — how could open data help her?For example, one team that included two police officers developed a persona for a “Concerned Citizen” named “Alexandria.” Alexandria is a middle-aged, tech-savvy woman who is concerned about crime and often asks for public safety information and crime statistics. According to her persona, Alexandria often attends community crimestat meetings and even recorded them on her smartphone to share with her Facebook friends.

By thinking so thoroughly about Alexandria and her goals, needs and behaviors, this team was able to come up with clever recommendations for their city. For instance, realizing that the city also wants to spread the word about what happens at crimestat meetings, they recommended that city public information officers staff share Alexandria’s crimestat videos on the city’s Facebook page or website. City staff also realized that, given that her ultimate goal was to address and reduce crime in the city, connecting her to data about crime prevention indicators – such as functional street lighting on the sidewalk – would empower Alexandria to do more than not just complain about crime to the city: she could advocate for positive neighborhood change, such as streetlight repair.

Another team developed a persona for “Charlie the Concerned Contractor.” According to his persona, Charlie often sought property and building information from city hall, including seeking a listing of properties that had been issued an “order to demolish” in order to locate property owners who might be seeking his demolition services.

The city was supportive of this goal, because they want to see their orders to demolish acted upon by owners. The user persona noted that Charlie accesses this information through a third party website’s property listings that re-uses the city’s open data. Informed by these details from the persona, one city staffer suggested the city could allow contractors like Charlie to sign up to receive email notifications every time an order to demolish was issued.

Takeaways

Not only did participants learn a lot from this workshop, but we did too. Here are a few of our key takeaways:

1. City staff already know a lot about the people who need information from city hall. City officials were able to draw from their experiences to come up with real examples of community actors who need city data. While specific user research is always preferable, city halls can and should quickly get started making their open data programs more user-centered by considering their existing relationships and brainstorming who their users of open data might be – and who they should be.

2. City staff with programmatic focus often know key details about current and potential users of open data better than technical staff. Many of the best details about goals, needs, and behaviors included in the open data user personas produced came from programmatic city staff. Police officers know about people who come to crimestat meetings looking for information. Public works staff know about the contractors who often seek information and services from their department. These relationships with people who have specific information needs is what gave the user personas life and led to key insights.

3. Any city can do this exercise. Despite many of our participants having no experience in open data, they generated insightful, actionable ideas in a short span of time. In just an hour, this exercise resulted in good recommendations to improve how cities share information online. Check out our full presentation slidedeck for detailed activity instructions.

Thank you to everyone who we met in Charlotte and who participated in this workshop. We look forward to facilitating this exercise with other cities participating in the What Works Cities program. In the meantime, we hope any city that is interested in connecting their open data efforts to users and to positive social impact will try this approach to get started!